In 1973, the one prisoner with whom I worked whom I absolutely knew in my gut was railroaded was a North Carolina moonshiner by the name of Cecil Lovedahl. Part of a group of returning WW2 vets who had taken up the manufacture & distribution of hootch, which was not only illegal, but horning in on what an older coterie of politically connected moonshiners thought was their monopoly, Lovedahl found himself at the wrong end of a plot to break up his goup. He had been riding in the back seat of a car that was involved in a fatal accident, killing the driver. The local pols saw it as an opportunity to break up the newcomers and charged Lovedahl with murder, though nobody could say why anyone in the back seat of a car would murder the driver while speeding on a dark mountain road. To escape a worse fate, his attorney (I forget whether he was a public defender or court-appointed) pled Lovedahl guilty over his own protestations in court, and he received a life sentence. Inside, Lovedahl deteriorated & attempted suicide several times, up to & including swallowing a box of straight pins. He would have been quietly released a couple of years later except for the fact that the prosecutor had risen quite high in state politics, with some thoughts of going even higher.

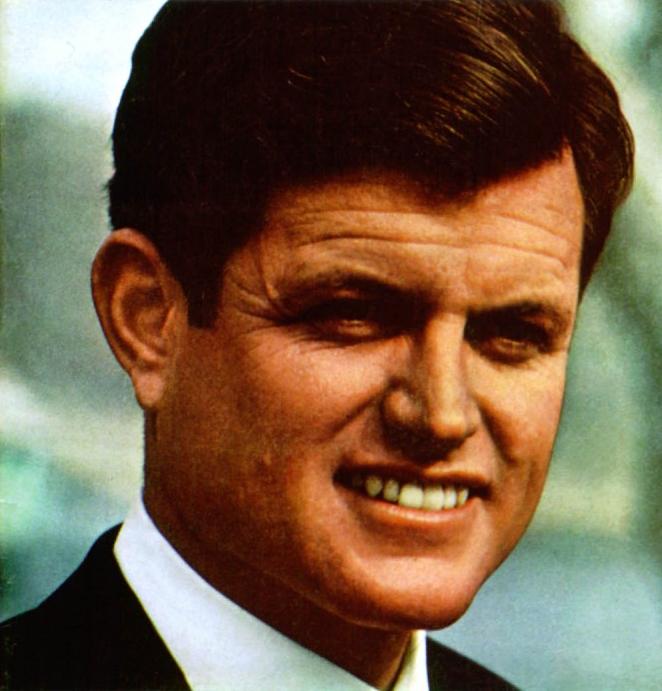

In my job at the Committee for Prisoner Humanity & Justice, I managed to arrange an out-of-state parole plan for Lovedahl through the Delancey Street Foundation in San Francisco, but I still had to persuade the North Carolina political establishment, and especially that pol, that putting Lovedahl on the streets 2,500 miles from home wasn’t going to come back to haunt him. There was only one person I knew who might be able to accomplish this, so I called Ted Kennedy’s office in Massachusetts. Without even once asking “What’s in it for me?” Kennedy made the call, and Lovedahl got his parole. That might have been the end of the story but Lovedahl broke parole – after 20 years in prison, he found Delancey Street’s restrictions hard to take – & headed to Nevada, where he was arrested as a parole violator. An extradition hearing was held, but it was easy for the Washoe County public defender to show that Lovedahl should never have been convicted in the first place. Free so long as he remained in Nevada, Lovedahl stayed there the rest of his life.

I’ve always wondered just how many times over 46 years in the U.S. Senate Kennedy made those kinds of phone calls. He was not only the one senator in 1973 who might have made that gesture, he was also the only one who could have gotten that result. I fear that the same may have been true as recently as last week.