I have always thought of Summer Brenner as a poet who sometimes writes fiction, so I was surprised to see in the front matter to I-5: A Novel of Crime, Transport, and Sex, that Brenner has published six novels to just two volumes of verse, and that she hasn’t published a book of poems in 32 years. Having now read – and completely enjoyed – I-5, I still think Summer Brenner is a poet, but one with notable narrative skills & a deep commitment both to her characters & to justice. I-5 is an effective novel, tho certainly not perfect, and one that would translate easily to the big screen. It has all the elements: a tough-as-nails hooker heroine who is also the protagonist & very much the “good guy,” plus a variety of secondary characters, minor Russian mafia wannabes, other prostitutes, a trucker with an illicit cargo, prison guards with their own demons & secrets, and a villainous capitalist trying to control everyone in his orbit. It has an ending that is both very much what the reader will be hoping for & yet almost

entirely a surprise.

I-5 follows the path of Anya, a young Russian woman kidnapped into the world of involuntary sex traffic, shuttled from brothel to brothel in the United States. The premise of the book is that she’s being moved from Southern California to Oakland where Mr. Kupkin, her “owner” very much in the tradition of slavery everywhere, plans to expand his empire of young women, duped or stolen mostly from Eastern Europe. To get there entails a ride up I-5, the great (albeit boring) north-south highway of the West Coast. As they proceed north, Anya, her immediate boss & pimp Marty, a comic thug alternately called Pedro & the Tarantula & a nameless young woman who will be delivered to a new owner along the way, they get caught in the Central Valley’s infamous tule fog as well as the valley’s one growing-like-gangbusters industry, prisons. Things happen, people get separated & we get to see Anya’s complex (and ambivalent) relationship to her own slavery. More things happen & Anya & Marty reach Oakland, though not as they’d intended. More things happen still.

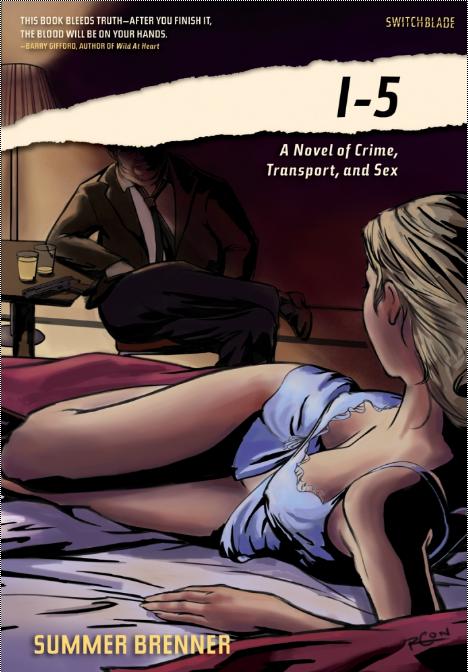

This is one of those books where you know from page 2, if not page 1, what Anya’s fate holds in store, though certainly not the what & how of it. Publishing the novel in a deeply noir format – Roderick Constance’s cover image is ironic without being comical – underscores what is predictable here, which is actually part of the fun of the book (how will Anya do it?). And Anya is the character here to whom Brenner is committed. To some degree, every other character in I-5 is defined by her, or at least by their function in her story.

If there are any weaknesses here, they’re relatively minor. Brenner gives us what amounts to a lesson in the history & meteorology of the Central Valley, setting up both the fog & the scene at the prison. This isn’t something Anya knows or understands, any more than she understands the back story of the young guard or of what Kupkin’s life is like in Atlanta. Brenner tells us all this & more because she wants us to know and in these postmodern times, nobody is worrying all that much about ontological or narrative consistency. If anything, Brenner makes great use of indeterminacy in the later chapters to reveal not just what happens but what can happen. But reading of the nature of tule fog or of the expansion of California’s prison system¹ feels disruptive – it was the one moment in the book where I could imagine becoming dislodged from the story itself.

Years ago, when she was writing the book that turned into The Adult Life of Toulouse Lautrec, Kathy Acker & I had a long conversation about the nature of character. The great trick of narrative or figurative literature, of course, is that the language on the page integrates syntactically not into a greater argument or expository structure, but instead to a displacement, an invocation of a referred world. A character represents a particular configuration of this referred world, and the difficulty of this displacement is such that we commonly acknowledge that the highest compliment one can pay to a character is that he or she is “believable.” Anya certainly is believable, but she also is a cipher, a symbol of the thousands – millions, if we think of sex traffic on its worldwide scale – of young women who submit to rape everyday. Brenner wants us to see this world through the eyes of one woman, someone young enough still to remember what hope is, even if old enough now in experience to understand just how difficult this is. I-5 is in this sense a political novel, though Brenner never lets this obstruct our view of her character. Anya is someone you will never forget.

¹ In my work in the prison movement, 1972-77, I was the lobbyist responsible for stopping funding for new prisons and was successful in each of those years. But it was already evident that the Department of Corrections, the guard’s union and far right rural legislators were bringing together the unholy alliance that would see the system explode from the nine joints I had to deal with in the 1970s to the 33 of today. The Department of Corrections is now the second largest police agency in the United States, second only to NYPD.