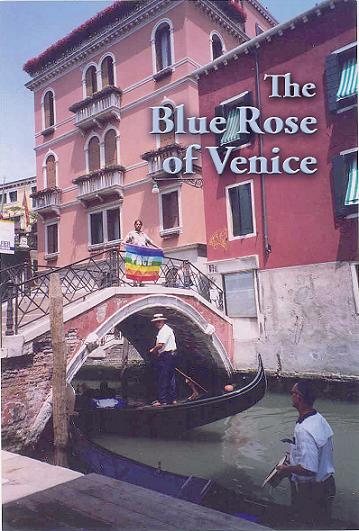

In the time it took for my computer to boot up, I was able to read, leisurely even, the whole of Thomas Rain Crowe’s The Blue Rose of Venice, from Mountains and Rivers Press in Eugene, Oregon. Crowe himself is from the far side of the continent, living in rural western North Carolina, and the six poems in this simplest of chapbooks are themselves set entirely in Venice during a trip there of less than a week that Crowe took with his wife, Nan. That’s him unfurling the flag in the cover image above, on the bridge at the Ponte della Guerra, an act – and photograph by Nan – described in some detail in the book.

I don’t, as a rule, have a lot of patience for poetry that is strictly narrative in the old sense of that word for the same reasons that I often find myself feeling antsy in a roomful of paintings by Andrew Wyeth (which, living just a few miles from Wyeth’s home town of Chadds Ford, it’s easy to do), even as I get it that Wyeth may have been the finest realist painter of the 20th century. But this suite, just 13 pages from end to end, 31 lines to a page, moves so smoothly that I don’t even begin to feel that twitch until maybe the end of the fifth poem. Crowe writes simply, elegantly, directly, without one instance of preening or false note in the entire book. Here is the shortest poem, “The Song of the Gondolier”:

Short bridges.

Narrow canals.

A single wooden paddle

from a black boat on dark water

the only sound

as

the gondolier begins to sing

eeoo, eeoo

into the evening

and the mouth of

a cellular phone.

While the other works may be narratively more complex – there are difficulties of language, politics, his relationship with his wife all to be negotiated – their values are not really different from the ones visible here. One might wonder, for example, about the preciousness of putting “as” alone on a line all its own, but it seems evident that Crowe wants to frame that image of the gondolier, to pause on it, as much as possible. The noun phrases of the first two lines, each treated as tho it were a sentence in its own right, both set the scene & articulate a rhythm against which the longer final sentence can unfold. You can read the final line as a small joke if you wish, but its moment of modernity – post-modernity even – is what contextualizes everything that has come before. It’s not a wildly ambitious poem, but it’s perfectly executed and I found myself reading it over & over, luxuriating in each moment.

To extend the analogy to painting a little further, I often find myself in a gallery or museum in front of some oil painting, moving my right hand as tho following each stroke of paint. To an observer, I probably appear to be conducting an invisible orchestra or presenting some spastic variant of air guitar, but I find it an excellent method to think with the painter as I look at the work & I find myself with a very similar instinct here. These aren’t poems that call for close readings in the New Critical sense, but they definitely reward an attentive eye. I don’t know Crowe’s work all that well, although he’s published a lot of books, including translations & interviews with jazz greats. He’s been an editor of Beatitude in San Francisco & you will find a number of his works signed at the other City Lights bookshop, the one in Sylva, NC.

This book is pretty much a perfect fit for Mountains and Rivers, whose Facebook page characterizes the press this way:

Formed in 1999, Mountains and Rivers Press publishes books that reflect the continued influence of mid-twentieth century poetics on American poetry (Objectivism, San Francisco Renaissance, English-language haikai etc.).

In an in-depth interview in Nantahala Review – with several poems and video clips of Crowe reading – that Crowe gave in 2004, almost certainly before this trip to Venice, he proclaims that he doesn’t want to have a “voice.” Yet the poems in The Blue Rose are entirely consistent with the values of the poems there as well. My sense is that Crowe’s voice is as clear as a bell, and as identifiable. I wonder a little as the disjunct between the professed position and the actual work, as I do also at the production strategies of Mountain and Rivers Press. You can tell that the press put enormous care & love in the making this chapbook, and yet I find the inexpensive white paper & the glossy cover give it a feeling that brings out that antsy feeling in me all over again. Thirty years ago, this is a book that almost certainly would have been produced on a letterpress on good paper with a matte finish. The cover might have been printed on handmade stock with a deckle edge. That is a norm that I find rapidly receding in today’s poetry, where the bargain basement production values of Lulu.Com seem to be invading the entire poetry market. The integral nature of the cover photo might preclude that approach here, yet the book reflects the Mountains and Rivers “look” throughout, and it makes me sigh. The press has some tremendous authors, Cid Corman, Jonathan Greene, John Martone & Bob Arnold among them. Its format seems to shortchange them all. In much the same way, I wonder what it means to disown the idea of a “voice,” as Crowe does, when his own is so very clear. In both instances, there is a gap between what is on the page – which is patently wonderful – and the page itself & how people seem to be thinking about it. I’m puzzled as to what that must mean.