I have lived with the poetry of Larry Eigner for 45 years. He turned 33 in 1960, the year the Allen anthology was published (and where I first read his work five years hence). When I started gathering poetry for a journal that would become Tottel’s in 1969, he was one of the first writers whose work I solicited & we began a casual correspondence that lasted until he moved, amazingly, to my home town. The board-&-care home where he first resided in Berkeley in 1978 was just down the street from the apartment building I’d lived in when I’d written much of Crow, my first real book, eight years before.

I knew about the palsy, of course, and it was evident that his parents in Swampscott didn’t think to keep him supplied with adequate typing ribbons, so that he often resorted to “filling in” what was otherwise too faint to read in letters or on cards, save that his handwriting was minimal at best. I recall David Gitin telling me stories circa 1970 about poets showing up at his home only to discover that they could barely make out his speech but I didn’t really get it until he arrived in Berkeley & I thought to call him to set up a time to come visit. A telephone call was not the way to meet Laurence Joel Eigner, but somehow I managed to comprehend that he’d agreed to the time I’d proposed & so we finally met.

Larry had actually been generous enough to blurb Crow, and you can read his blurb, a note really, there among his Collected Poems – it’s entitled “b i r d s d a n c e c r o w” on page 1010 in volume III of Stanford’s monumental publication project, dated May 15, 1971.

During his not quite 18 years in Berkeley, Larry was mostly someone I would see at readings or at parties & I would find myself helping from time to time getting Larry & his wheelchair up the long steps to Canessa Park for the readings there. When the University Art Museum of Berkeley held a celebration of his work, mounting some lines of his work on the outside of the building, holding a reading in the auditorium, Kit Robinson & I did a show for the university radio station, explaining that Larry was not in any sense a disabled poet, but rather a great one who happened to have physical limitations.

And when Larry died in February of 1996, I was already living here in Chester County, PA, just about to move into the home from which I’m writing today. I had not yet been away from the Bay Area for nine months, but it was Larry’s death more than anything else that truly marked that breach for me. Looking at his collected poems some 14 years later takes me instantly back to that profound sense of loss I felt on learning that he was in Alta Bates Hospital & not expected to pull through.

All of which is to say, by way of preface, that this note today is unlikely to be all I’ll have to say about the four-volume Collected Poems, edited by Curtis Faville & Robert Grenier, two friends who likewise stretch some 40 years across the arc of my life.

But I’ve been asked six or seven times what I think about the “controversy” of the collection’s layout. And therein hangs a tale &, I think, a lesson.

When I first heard that Faville & Grenier planned to have the book published in Courier typeface, I wrote & asked each not to do it. I was very much fixated on the impact this decision made on Robert Duncan’s work. Publishing Ground Work: Before the War in courier so as to replicate as much as possible Duncan’s typescripts was one of three disastrous decision that Robert made – the other two being to hold off on publishing a book for a 14-year hiatus & making a poor choice in a literary executor – that took Duncan’s writing from being widely read & considered – even by the likes of Harold Bloom – as on a par with that of John Ashbery to becoming something of a footnote from the 1970s. One hopes that the efforts of Lisa Jarnot & Peter Quartermain, the first with her biography, the second having taken over the editing tasks of getting Duncan’s work back into print, will rescue that situation. But my immediate instinct was to imagine that this might be a disaster.

I was wrong. The editing decisions that Faville & Grenier, combined with the design work of Stanford University Press, have made this one of the richest & most readable collections that I own. Thumbing through the book in a store ought to be enough to persuade one of this, I should think, except for the fact that a four-volume set that can only be purchased in the aggregate (for the not inconsiderable price of $150) is not something you are likely to find anytime soon in your mall bookshoppe. No, this book is not perfect, and there certainly are issues that can be usefully discussed. But I’m not persuaded that the design of the volume is where one’s energy might be best spent.

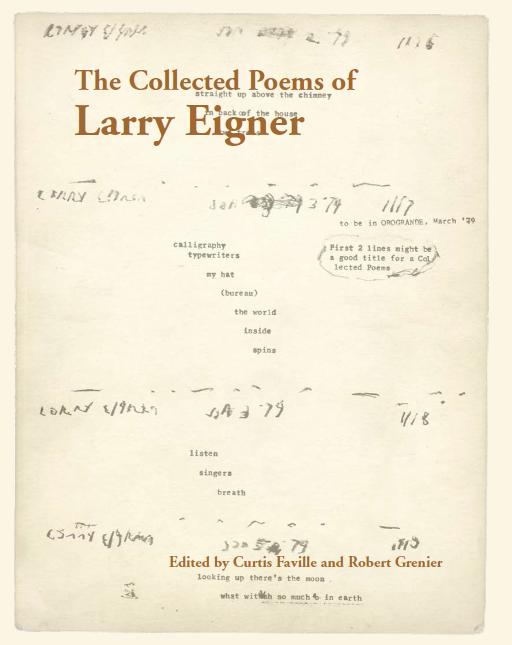

Consider, just for a moment, the poem that figures on the book’s cover in each of the four volumes. On the first, we see just the initial couplet, calligraphy typewriters. On the second, the entire poem. On the third, the original page of Larry’s manuscript that includes a note that reads (circled by Larry’s pencil):

First 2 lines might be

a good title for a Col

lected Poems

On the final volume, we see the entire page of Larry’s master manuscript. (Click on the images above to expand each photograph.)

This sequence – initially Faville’s idea – communicates powerfully not just the materials as he & Grenier found them, but I think they also pose some of the key aspects of the decision-making in setting up this vast collection. First, that suggested title alone tells us Larry’s position on this issue – that spacing & visual presentation are critical in understanding his work. At 7.5-point type on a 12-point line, the Courier is readable throughout the work while maintaining the feel of the typewritten, and the uniform width of the letters that is essential to the presentation of these poems. By moving the majority of the texts left, Grenier & Faville have given themselves adequate room to incorporate Larry’s infrequent longer works that – like all his mature writing – sweep across the page as left-hand margins invariably stagger to the right. Any other decision would have generated a hodge-podge visually.

What Duncan got wrong that Grenier & Faville ultimately got right was an understanding that a book, as distinct from a poem, is an inherently collaborative project. Any compromises that have been made are to the advantage here of the reader, and it shows. F&G include some representative texts at the end of Volume IV (and an essay by Faville, “The Text as an Image of Itself”) that demonstrate the issues the editors faced in coming up with the visual presentation of the book. Could this have been done another way? Perhaps, but not nearly so well.

The real issues in this book are elsewhere. There are, as Steve Fama has noted, two poems that were inadvertently omitted, a remarkably low errata rate for a collection that is 1800 pages long, not including significant prefaces, appendices and notes. That amounts to a nit. One might argue for a less personal introduction at the start of Volume I, one aimed at unfamiliar readers. And I'm sure that the facsimile publication of a collection of poems from eighth grade at the start of the first volume will have its non-enthusiasts as well. I would have put it in an appendix.

But the larger question has entirely to do with distribution. At this size and this price, one cannot expect every young poet in America to rush out & buy the collection, even though they should. It’s aimed frankly at libraries, and at people who take their poetry very seriously. This gathering really shows the degree to which Larry’s reputation ultimately will have to rest on somebody producing a good Selected Poems, something that can be issued in paperback & used in a classroom, containing maybe just 500 of the 3,000-plus that are found here. That collection is going to be much harder to edit.

Eigner is hardly alone in this regard, we need a pocket Berrigan (beyond, that is, The Sonnets) & the fate of the selected Williams & Creeley volumes (or the competing O’Hara selecteds) all demonstrate how problematic such projects can be. But they’re necessary for the same reason that all the overlapping editions of Dickinson, Stein or Shakespeare are, because these are such important writers & figure so critically in defining who we are & can be. Until that volume, an Eigner for the masses, is available, tho, keep in mind that The Collected Poems of Larry Eigner is the most powerful & substantial book of this millennium – and this could still be the case a century from now.