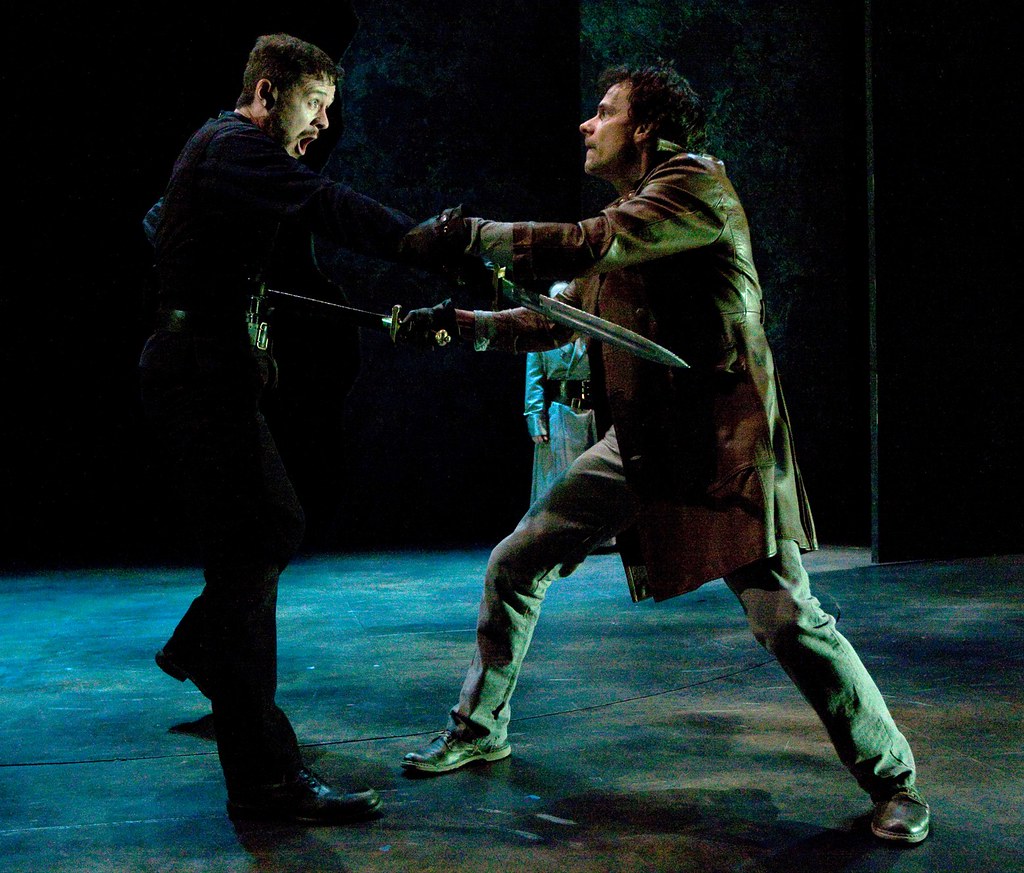

Kevin Bergen as Edmund, left, & Christopher Patrick Mullen as Edgar

I happened to catch the People’s Light production of King Lear the other day, which reminded me yet again of how at its best this troop, now in its 35th season, can be one of the finest regional theater companies – an organization whose praises I’d heard all the way back in the Bay Area before we moved just a couple of miles from its stage back in 1995 – but at its more pedestrian is not so many notches up from any group of well-intended community players. Lear unfortunately is at the wrong end of that spectrum, with just two genuinely inspired performances: Graham Smith in the title role & Christopher Patrick Mullen as Edgar, Gloucester’s legitimate son who is cast out after having been framed by the bastard Edmund. The direction is muddy, with not a single scene ending crisply. Some of the performances are cringers (one character waffles between British & Southern accents, Mark Lazar’s fool waivers between too broad & inaudibly mumbled).

Still, it is virtually impossible to drain all the drama & majesty from this best of all plays unless you rewrite Shakespeare’s script. Happily, nobody is feeling so bold as that. Lear is one of those reminders that great writing really is inexhaustible. One could explore its depths forever. One of my sons noted that it’s interesting that this work, which is so central to the English-language theater, is, like the “founding” novel of Don Quixote, at some level a play about Alsheimer’s disease, a category neither Shakespeare nor Cervantes might have imagined.

The medicalization of personality over the past century, the submission of every action to a diagnosis, is inescapable. It doesn’t render narrative obsolete, but it does make an awful lot of the poetics of persona seem just plain silly. The tough guy alcoholic isn’t an update on Bogie, but rather somebody who needs an intervention. And a lot of persona poetics comes over as just plain clumsy – a writer who tries to stay “in character” for ten lines almost always strikes me as unreadable. Far from bringing the figure into focus, it does just the opposite. If you want to play with persona, much more engaging in this post-DSM world is something like Linh Dinh’s Some Kind of Cheese Orgy, whose speakers wear their personae fitfully & resentfully. A “person” in that book figures more as a kind of crowd & it’s no accident that John Yau in his blurb on the Chax website invokes not just Mayakovsky & O’Hara, but Shakespeare’s Falstaff & Celine’s Bardum. “Pulsing energy” indeed. Linh Dinh at his sharpest feels a lot like sticking your finger, or perhaps your tonuge, into a live socket. The circus is in town.

My favorite line in all of Shakespeare occurs in Lear, spoken on the heath by Tom-a-Bedlam, the psychotic portrayed by Mullen’s Edgar, yet another Shakespearean character that proves a shape shifter. It’s a single sentence & Mullen, as he voices it, has just shed the last of his clothes: Edgar I nothing am. I think of it as the Russian doll sentence. Each word can be read by itself as a statement of being, a naming of essence or immanence, starting with the most social, ending with something closer to pure presence. It doesn’t engage syntax save as concentricity. Each word is nested within the term that came before. This is a degree of compression, condensare as Pound would have put it, unequaled not just in Shakespeare, but in the English language. It’s why Shakespeare remains special after all these years.

The close reader here will note that my next-to-last paragraph invoked Bob Dylan as well as Linh Dinh & I do think it’s just this sort of multiplicity that makes Mr. Z’s finest songs what they are, as is true also for the poems of Larry Eigner (or, for that matter, Barrett Watten, John Ashbery, Rae Armantrout, the John Berryman of the Dream Songs, or the Hart Crane of The Bridge). “How crowded is it?” is a question we ought always to ask ourselves about any piece of writing. If there is a single feature that connects different genres, different centuries, different aesthetics, that’s it. If there isn’t a mob, why bother?