Yesterday’s Songs

Homer sings the gods

of war,

Homer sings

“Uptown

Girl.” He strings his lyre

w/ piano

wire

if he’s got

the notion, molds calliopes

from white

bread then throws them

to the wine-soaked

ocean.

That was one of the poems I was thinking of the other day when I characterized Chris McCreary as a New Precisionist. It’s not just careful use of couplets a la Williams that I’m drawn to in Undone: A Fake Book – tho I’m always a sucker for those – so much as it is the balance of mythological & pop culture elements, & the extraordinary care with which he deploys sound – hear how the reiteration of long e sounds sets up the string of long i that follows, which in turn set up the rhyme of closure: notion / ocean. Sonically, this poem is as tight as a bear trap.

It’s hard to imagine, say, the Oppen of Discrete Series demonstrating so much play with sound. The Oppen of This In Which and The Materials would think it distracting. But I suspect that Oppen would find Graham Foust too full of Stevens, and Joseph Massey not so much too full of Creeley, but rather focused on the wrong Creeley, the one of Words and Pieces.

Which is why I think that the New Precisionism isn’t simply neo-Objectivism (even if I were willing to redact Objectivism down to the Oppen of the 1960s), although that may be one pole & Oppen absolutely is an influence on all of the writers I would identify as precisionist:

Disinvited

The romance of

shipwreck &

inevitable an eighth day’s

fever, some

Stratego mixed

w/ bits of necromancy

& so this mess

you’ve left,

i.e. attachment

to one’s captor, e.g.,

one pissed-off Tinkerbell,

or, c.f.,

another day of nickels,

the countless fallen

robins, et

cetera. Cannonball,

the boy calls, & then he leaps

overboard.

There are multiple games at play here, one of which might be characterized as Having Fun with Oppen, the difficulty being that “having fun” isn’t a phrase in the Objectivist Playbook at all. Another, even more pointed object of McCreary’s humor might be characterized as the twitchy, notational style that descends not from the Objectivists so much as the Projectivists, Olson, Duncan, Creeley & Blackburn, with a look back to Williams & to Pound. This starts with my beloved ampersand in the second line, then continues w/ “w/” in the third couplet (which [or wch] also raises the possibility that this is what McCreary means by “necromancy”), before slathering it on heavy: &, i.e., e.g., c.f., et / cetera (that linebreak strictly for sarcasm) before closing on the final ampersand, every much a big splash at the end as that produced by the narrative boy. Are we supposed to hear canon in Cannonball? I found it impossible not to do so, & even typed it out that way the first time.

A text like this throws up many more questions than answers in its wake, which is (to my reading) one of its great attractions. If this were fiction, it would not be the perfectly woven rug of a Nabokov or Fitzgerald so much as a Philip K. Dick romp, spurting new ideas, new beginnings every few paragraphs until the reader is lost in possibilities. Yet – more like Nabokov than Dick – McCreary clearly loves control. Nothing here has been casually spun out.

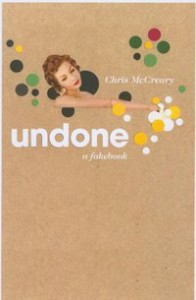

So what if we plopped George Oppen down at the King of Prussia Mall? The shipwreck of teen culture might turn up an almost Dante-esque mode of the comedic – McCreary himself is not so old as to have forgotten (& his twins will taken him back there soon enough), plus he teaches high school for a living, albeit at one of the elite private academies that dot the Philadelphia suburbs. A Fake Book, the subtitle here, accentuates the irony. The term comes from music, jazz specifically, for those print jobs that offer just enough detail for an adept to utilize as grounds for improvisation. What, in this sense, do we make of that title, Undone? That we are undone by our culture? That fake books themselves are often just loose sheets of paper, literally unbound? That what we are to read herein has a sketchy, improvisational relationship to the world(s) to which it alludes? Is the author here no more fixed than the ghost of Homer, or whomever is meant by “an eighth day’s / fever”? All-of-the-above, I think, and more.