In 1965, when I first saw Allen Ginsberg at the Berkeley Poetry Conference, he was introduced as a man who had just been harassed by the police in Prague & expelled from Czechoslovakia. At that same conference, Charles Olson gave such a rowdy & endless “talk” that campus security finally cut the power to the room to shut it down. Immediately after the conference, Louis Simpson, a UC English Department professor, announced he was accepting a position on the East Coast because there was no support for poetry in a place like Berkeley – it was apparent that he meant his kind of poetry. This was carried in the local papers with none of the requisite contextualization.

Just 18, I was already reading the likes of Norman Podhoretz’ attacks on the Beats. And I’d read the introduction to the Allen anthology, which made clear that the feeling was mutual. If I had missed the coverage of the Howl trial in the local media when I was 11, I had certainly seen the coverage of the various court cases of Lenny Bruce, so was hardly surprised when the San Francisco police in 1966 attempted to prosecute both Michael McClure’s The Beard & Lenore Kandel’s The Love Book for obscenity. Since a standard defense of any artwork from an obscenity prosecution in those days – a vestige of the Ulysses trial decades before – was the value of the art involved, I dropped a note to the San Francisco Chronicle suggesting that The Love Book represented an important opportunity to defend the right of a mediocre work to use the same four-letter words. Soon enough, I had the opportunity to watch Robert Duncan (whom, at that point, I barely knew) denounce my reactionary failure to recognize the “new language of love” that Kandel had pioneered, both at a large rally at San Francisco State & on KQED TV.

Kauri, the very first magazine I ever published in that was not edited by a personal acquaintance, had in the issue where I first saw my work some angry letters, one by Eleanor Antin, denouncing something that had appeared in an earlier issue that had called an artist who was a personal friend of hers, Andy Warhol, a charlatan. At SF State, I squirrelled myself in the library’s poetry & rare book collections, where in Black Mountain Review, I could find Robert Creeley’s furious denunciations of what I today would call the School of Quietude. Elsewhere, another of my early editors, John Sinclair, was being harassed by the police in Detroit for his role as the personal embodiment of sex, drugs & rock-n-roll – especially that middle item – while in Cleveland the cops did their best to discourage d.a. levy, who would in fact commit suicide.

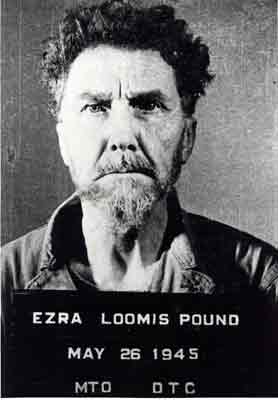

Once I transferred to UC Berkeley in 1970, I again squirrelled myself away in the library where I read on microfilm the complete, unedited letters of Ezra Pound, and it became utterly clear that this sort of combative behavior had been going on in poetry for the better part of a century (much longer, in fact, as I know now – what is Dante'sInferno but a massive settling of scores, or the work of Catullus for that matter, trash talking his peers?).

Poetry, it was clear, was a contact sport. If there was a commissioner of poetry, Vince McMahon might be a logical choice for the role. Yet I can’t think of any of the sundry poetry wars of the last century without hearing this verse from one of my favorite songs by Bob Dylan:

Praise be to Nero’s Neptune

The Titanic sails at dawn

And everybody’s shouting

“Which Side Are You On?”

And Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot

Fighting in the captain’s tower

While calypso singers laugh at them

And fishermen hold flowers

Between the windows of the sea

Where lovely mermaids flow

And nobody has to think too much

About Desolation Row

The genius of that lyric, written 45 years ago, was that this debate between literary types & traditions was even then being posed in either/or terms for popular audiences by the lightly schooled autodidact of the folk-rock scene: Which side are you on?

And that Dylan was already posing the quarrelsomeness of the poetry world as something ludicrous.

The poetry scene of 1965 – the year I first saw Ginsberg & when Dylan wrote those lyrics – consisted of a few hundred souls. Today, with at least 20,000 publishing poets, the dynamics of the scene are really quite different. And the debates between kinds of poetry take on a very different flavor if they only involve a few of the practitioners off mud wrestling in a corner.

One thing should be clear: many of the new entrants to the scene have no interest in old conflicts or in the idea of conflict in poetry under any terms. One might see this as an ordinary enough result of the gender rebalancing of the scene over the past five decades. But it’s also part of a deeper critique of society that no longer valorizes the self-destructive credo of the poet-as-addict. Or envisions the poet as warrior in a world in which real warriors leave so much devastation in their wake. It’s a different world. Dysfunctional male behavior is not glorious. It is in fact pathetic.

To which some people seem completely oblivious. I have tried policing my comments stream over the past couple of years, and – as I noted the other day on Jessica Smith’s blog – I routinely reject a half dozen comments every day that are sexist, homophobic or anti-Semitic. Moderating the comments stream at times makes me want to take a shower. Worse yet, one of the consequences of my rejecting the more overtly vile submissions would appear to be that I have inured myself to the merely despicable level of chatter that can go on.

I don’t mind debate, even vigorous debate, over fundamental issues. But it does seem clear to me that some people make a point of verbally attacking writers I praise on this blog simply because I’ve praised them. Reading that responses to a positive review on my blog seriously discouraged Jessica Smith about poetry & writing is as depressing a consequence as I can imagine. I want to apologize to her for not doing a better job policing the comments stream, and I want to apologize to Joseph Massey more recently for the same. And to Barbara Jane Reyes and any other poets who feel they may have been unfairly treated in the comments stream.

I have of course read some comments that suggest that poets who feel bruised by such behavior need not to be so fragile. But I think everyone has every right to feel exactly what they feel, and that participating in poetry doesn’t have to mean submitting oneself to hazing by yahoos.

Recognizing this leaves me with few options. I could shut up, although I actually don’t think that’s the goal of most of the comment harpies. I think I give them a venue that their own blogs may not, and that this is really what much of this is about. I could reject a lot more comments than I do, not simply those that characterize someone as a “Jewette” or “French cunt.”¹ Which is one more bit of labor for which I don’t have the time or energy. Or I could turn off the comments stream altogether, which is the option I’m taking.

You can still write to me – the address is in the left-hand column – and once in rare while I might republish a note if it seems worthwhile, but I will ask your permission first. If you respond to something here in your own blog, I may well link it to in one of my weekly roundups – I’ve been doing that for years. But I’ve also ignored a lot if I thought they were just being stupid or name calling. That seems like a good thing to continue. And so I shall.

¹ Directed at writers who were neither French nor Jewish, for that matter.