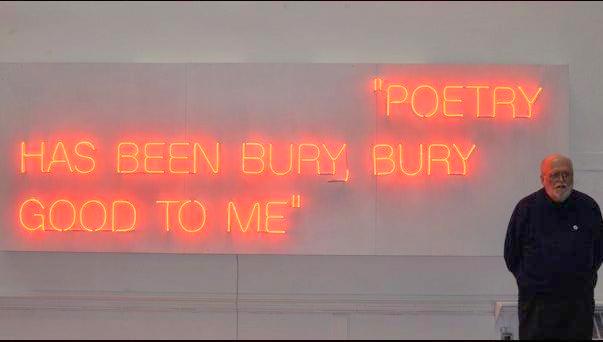

After a long, intense day of events at the Text Festival in Bury – the morning spent at the museum where my neon excerpt from the still-in-progress Northern Soul has become the public face of the festival itself, the afternoon at a reading in Bury Parish Church – the building dates from the 19th century, the congregation from circa 900 – to an evening at the Met where mostly a sequence of sound and performance poets (but nary a sign o’ slam) tickled & occasionally ripped at our ear drums, I found myself the next morning reading Sarah Riggs’ 60 Textos, simple one-stanza lyrics (or perhaps anti-lyrics) feeling that there was more that was genuinely new in her tiny poems than I had seen the entire previous day, even as I’d been immersed work that everywhere proposed itself as new (my own included) but was in fact something different altogether.

The axes that converge in something like the Text Festival – poetry as visual art, as performance, as sound – have their roots in traditions that are at least 100 years old (in the case of the Russian Futurists or the Dadaism of Hugo Ball, twice that or more in the case of William Blake & illuminated manuscripts). It’s fascinating to watch Christian Bök build a career out of two or three very divergent types of work: obsessive, jaw-droppingly brilliant contained projects like Eunoia or the ongoing Xenotext; performance poetry that draws knowledgeably from the masters of Futurism, Dada & fluxus; sound work that extends the legacy of Steve McCaffery, bpNichol and the Four Horsemen in Canada. But it’s those obsessive projects of his that represent something transformational in poetry. Much of the rest of it is theater that enables him to go places, entertain & build a public presence. That’s more about marketing than innovation, tho Bök is as thorough a scholar of performance poetics as I’ve ever met. Nor is there anything new, as he himself acknowledged, about him writing a set of responses to the questions of my work, Sunset Debris. Alan Davies beat him to that over 30 years ago, and such responses are threatening to become a genre (or at least genre-twitch) of their own. What’s new in Bök’s approach is the use of a computer program and artificial intelligence to “write” the responses. Frankly, it’s refreshing to hear a machine forced to admit repeatedly “I don’t know.”

Likewise my neon sign, Tony Lopez’ poem modeled on a railway station “click sign” (or whatever they’re called) or Maria Damon’s needlepoint can’t be called new in any way that is meaningful within poetry. That’s not the value they’re proposing, any more than Holly Pester does when she winks at the whole idea of the future within futurism by adapting a sea shanty for spaceships. Rather, the value is – as it should be – on the question of Is the work any good?

On that score, the Text Festival was more mixed as an experience. My performance was, as I noted at the time, easily the most old-fashioned presentation at the festival, a man with texts reading aloud, even if one of the texts appeared on the back of a “baseball card” & another was excerpted in the mode of a neon sign. Other poets who likewise followed this format – Marco Giovenale & Márton Koppány – were among my favorites at the festival, not because we are kindred spirits (tho we are), but because their use of a multilingual textuality shows the true globalization of language in a way that completely overturns the prestige & intimidation aspects of Ezra Pound’s invocation of the linguistic other into The Cantos. Both made me painfully aware of monolingual limit of my own practice as poet, simply because they so effortlessly go beyond. Globalization means something very different to Europeans of their generation than it does to Americans of my age cohort, let alone to expats like Pound who never fully got with the 20th century, let alone imagined the 21st.

But other projects at the Festival felt almost nostalgic in their neo-dada, post-Fluxus (Fluxonian?) machinations, reading the text ostensibly on newsprint, then stuffing it into your mouth. And yet the young Catalan poet who did that also “translated” Paul Celan into a sound text using at least three languages in a way that would have blown any of slam poets you might think of off the stage. It felt like an instance of the old & new wrestling with one another, perhaps in a way that is more vulnerable than Bök’s because it is less clear as to when it is tackling something genuinely new & when it’s just gloriously riffing on the old because it feels so good (as, say, would be the case in the US with any “Beat” poet younger than, say, David Meltzer). As with the Beats, the very last thing that Dada & Fluxus are in 2011 is new.

I prefer the concept of the post-avant precisely because the concept of the avant-garde is looking more than a little tattered & dated. The May 1st celebration of Kurt Schwitters’ Ursonate at the festival makes perfect sense as a recognition of community & tradition, even if the work itself might be viewed as an assault on such notions. Schwitters was in fact interred in Bury during WW II, so this is something akin to post-Projectivists celebrating Pound on the grounds of St. Elizabeth’s. That’s a very different set of values from Make it New. And, I suspect, a more lasting set of values as well.