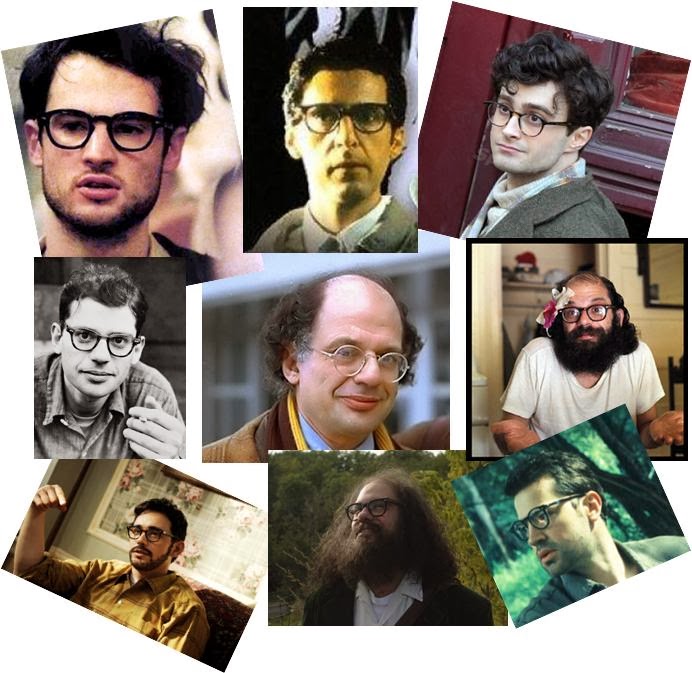

Many Allen Ginsbergs - only the middle row is real

In

2008, the late Carolyn Cassady, one-time wife of Neal – Jack Kerouac’s

trickster muse – revealed some lingering bitterness in an interview when she

remarked that as “far as I'm concerned, the Beat Generation was something made

up by the media and Allen Ginsberg." That’s an unfair dig at Ginsberg.

When Lawrence Ferlinghetti & Shig Murao were prosecuted for the sale of Howl, Ginsberg – who became a household

name from the resulting media coverage – stayed as far away from the trial as

he could. It would have been a far better – even obvious – career move for him

to have been sat in the front row of the courtroom in support of Ferlinghetti

& Murao. Instead, he stayed as far away as he could &, when the chance

presented itself, didn’t take a victory lap after the City Lights publisher

& his book seller were vindicated, but instead hightailed it to India.

This

was well before Ginsberg got to watch fame, alcohol & the media celebrity

machine tear Jack Kerouac limb from limb, a painful public process that led to the

novelist’s demise first as a writer & then as a person. Indeed, it might

not have been until Ginsberg’s stint as Kraj Mahales, the King of the May, in

1965 Czechoslovakia – to which Ginsberg had been deported from Cuba of all

places after protesting Castro’s persecution of gays – that the author of Howl seemed fully to appreciate his own

potential as a symbolic public figure. But even then other poets rolled their

eyes & looked askance. Jack Spicer’s very last poem, written just weeks

after Ginsberg expulsion from Czechoslovakia, accuses Ginsberg of not

understanding that “people are starving.”

That

was 48 years ago &, if anything, the mythos of Ginsberg & radical beat

culture as a forerunner of all things liberational has intensified over the

past half century. In a five-day span late last fall, I saw three separate

motion pictures, either current or very recent, that each included Ginsberg:

- John

Krokidas’ Kill

Your Darlings, starring Daniel Radcliffe as the future author of Howl, Jack Huston as Kerouac & Ben Foster as William S.

Burroughs, which may still be in some theaters

- Walter

Salles’ On the

Road, an attempt to contain Kerouac’s sprawling autobiographical novel as an

intelligible film narrative starring Sam Riley as Sal Paradise (Jack Kerouac),

Tom Sturridge (like Radcliffe, a British actor) as Carlo Marx (Ginsberg) &

Viggo Mortensen as (as Bull Lee, Burroughs), relatively new to the Netflix

& DVD round after a modest theater run

- Robert McTavish’s documentary, The Line Has Shattered, recounting the 1963 Vancouver Poetry Conference, during which 48 “students” took seminars & participated in readings over three weeks from Allen Ginsberg, Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Denise Levertov & Margaret Avison – this film is still rolling out via the art film / festival circuit

Ginsberg’s

stature on the curious fulcrum between public intellectual & public

anti-intellectual is worth noting. In addition to Radcliffe & Sturridge,

Ginsberg has also been portrayed by Roger Massih, Wade Williams, James Franco,

Charley Rossman, Hank Azaria, Yehuda Duenyas, David Cross, Tim Hickey, Jon

Schwartz, Ron Livingston, Bill Willens, John Turturro, Richard Cotovsky, David

Markey, Ron Rifkin, & George Netesky. David Cross, who played Ginsberg in

in the Dylan anti-biopic I’m Not There, plays

Allen’s father Louis in Kill Your

Darlings.¹

All three of the three films I saw are flawed, yet none is particularly bad or in any way unwatchable. And one could make an argument for each that explains why it is the strongest at something. Kill Your Darlings narratively works best as cinema, if only because Krokidas and his co-writer Austin Bunn set out to construct a tight little narrative machine and do reasonably well. Salles – best known for Motorcycle Diaries – tries to bring the whole of On the Road faithfully to the screen and does a not dreadful job, given that the strengths of the book – its fantastic (and fantastical) descriptions & Benzedrine-locomotive prose rhythms – don’t translate easily to film, particularly when the scenes so depicted are themselves often quite static. With blues backgrounds, some terrific 1940s sedans & handheld cameras to suggest energy when there isn’t much, Salles does what he can to bring an inherently resistant piece of writing to film. That it doesn’t hold together, especially at the end, is a sign of the director’s integrity as much as anything else.

The Line Has Shattered does

a great job of portraying the 1963 poetry conference Warren Tallman put on at

the University of British Columbia, which it notes was “mis-sold” to the

Vancouver public by the local media as an instance of the Beats coming to UBC

when in fact it was – as the documentary also notes – mostly the Projectivists

(Olson, Creeley, Duncan & Levertov), with Allen Ginsberg counterposed “to

stir things up.” The “students” at this summer program are themselves a Who’s

Who of the post-avant networks of the 1960s right up to the present, including

two future Canadian poet laureates, George Bowering & Fred Wah, as well as Phyllis

Web & Daphne Marlatt, plus some noteworthy Yanks that included Drummond

Hadley, Larry Goodell, Michael Palmer & Clark Coolidge. David Bromige,

raised in London & at that moment making the transition from Canadian to US

poet, was there as was Bobbie Louise Hawkins, presumably accompanying her

then-husband Creeley. Midway through the proceedings Philip Whalen turned up.

All

three films stress the degree to which the poetry of the period – at least the New

American poetry – posed an assault on a prior culture. On the Road literally shows confrontations with cops & the

phrase “poetry wars” in The Line Has

Shattered has nothing to do with language poetry, Naropa, Kenny Goldsmith

or flarf. In this, the films are all quite on target, although each film muddies

its message in how it attempts to articulate this cultural divide.

In

one sense, On the Road is visibly

weaker than the other films in that it suffers from several uneven performances

– Garrett Hedlund isn’t remotely like the real Neal Cassady & plays him as

a muted Brad Pitt out of Thelma &

Louise, tho Salles takes pains to demonstrate that what made Cassady such

an attractive model for Kerouac wasn’t anything fancier than bipolar disorder,

an interesting proposition. Sam Riley’s Kerouac / Paradise also feels off, as

if Riley were trying to decide whether to play James Dean or Twin Peak’s Kyle MacLachlan. Riley’s

best scenes are all when he’s writing into his notebook, but there is way too

much staring thoughtfully off into the distance. Mortensen’s Burroughs is a

step above a Saturday Night Live impression,

especially when compared with Ben Foster’s rendition in Darlings. Mortensen, whom I usually think of as one of the more

interesting actors alive, is filmed as if Salles is trying to hide his

performance.

Kill Your Darlings has

an advantage, perhaps unfair, in that one of the key relationships in this

story involves two people largely unknown to the audience, Lucien Carr &

David Kammerer, portrayed by Dane DeHaan (brilliantly) and Dexter’s Michael C Hall (not so much). Their relationship, which

ends up with a death, is the key to the film. Ginsberg et al form a secondary

narrative, there for context, given more screen time than is narratively warranted

because of who they are. But this film would worth watching just for the

performances of DeHaan, Radcliffe & Frost even if they were portraying

Alvin & the chipmunks.

One

area where all three films struggle is the sexual politics of it all. The

period between the mid-1940s and early 1960s were a lousy time to be a woman or

a sexual minority. Darlings shows

Ginsberg gradually coming out to himself, while the Kammerer-Carr affair is

wrought with all the cultural baggage of the period right down to homosexual

panic being treated as grounds for justifiable homicide. On the Road presents an even more complicated picture, presenting

Cassady & Kerouac in bed simultaneously with MaryLou / LuAnne Henderson,

portrayed by Twilight’s Kristen

Stewart. Of course that means that they’re also in bed with each other, and the

film seems to want us to notice that, even as it portrays Kerouac in an

ultimately homophobic light. In contrast, Kirsten Dunst & Elisabeth Moss do

what they can with largely thankless cameos demonstrating how women conflict

with the “spontaneity” / irresponsibility of their men. Their role is to fuck

the men, take care of the resulting babies & it wouldn’t hurt if they also

supplied the funds & cooked the meals. Amy Adams steals her scene as

William Burroughs’ wife-(& shooting victim)-to-be, rather in the same

manner that Jennifer Jason Leigh does her tiny role as Naomi Ginsberg in Darlings, by suggesting that all the

feigned madness of the naughty boys pales beside the real deal.²

In

Vancouver, in “real life,” the gender issues aren’t any better. The male

faculty – Olson, Creeley, Duncan, Ginsberg -- are given three weeks to teach,

the two women

just a week each and Avison is distracted dealing with the death of a parent. No

mention is made of amorous arrangements or bed hopping, so that the manifest

gender issue of the conference proved to be Levertov’s reading of “Hipocrite Women,” 2/7ths of

which reads

And

if at Mill Valley perched in the trees

the

sweet rain drifting through western air

a

white sweating bull of a poet told us

our

cunts are ugly—why didn't we

admit

we have thought so too? (And

what

shame? They are not for the eye!)

The film notes the poem

& surrounding controversy but fails to fully explore the text, either as a

response to the misogyny of Jack Spicer (not present at the ’63 conference,

although he would loom large at the 1965 one shortly before his death), or in

terms of the misogyny of the conference itself, or (especially) in terms of its own self-loathing. Of the 48

students registered for the affair, two-thirds were men, and it’s telling that the most famous image

from the event is a posed photo of ten participants, Bobbie Louise Hawkins and

nine guys.

There

is a universal sense of gay liberation as something everyone agreed upon that

seems untroubled and revisionist in contrast with the woman question here.

Which

points to the fundamental flaw in each of these films – and more than a few of

the others that have covered this same period & these same poets – an

awe-struck reverence that fails to ask the

important critical questions that linger unspoken. The Line Has Shattered is perhaps the best example of this

conundrum because it proclaims so loudly that the poet-teachers came not with

answers, but with questions of their own. This is then contradicted by the film’s

own foregrounding of Creeley’s form is

never more than an extension of content rather like a tablet from the

Mount, and quite unquestioned by the surviving attendees, who seem – especially

if one follows the logic posed in the film by Michael Palmer and Clark Coolidge

– to be taking the Projectivists’ open hostility to New Criticism to be a clarion

call for anti-intellectualism in general. I don’t think this is a fair

representation of what either Palmer or Coolidge believe in practice, but

seeing them portrayed as pawns for that particular chess move is truly

cringe-worthy. Worst of all, it fails to probe the limitations of Creeley’s rubric,

which he himself was quite ready to concede in his later years.

For,

regardless of the insights & pronouncements of the Projectivists, the Black

Mountain poets no more took over the poetry world than did the Beats. Each

group opened up an important vein of exploration that these writers &

others subsequently fleshed out. But talking about either formation without a mention

(let alone discussion), say, of the New York School is ultimately doomed. Fictional

films can be freer than documentaries, as a form, in how they explore a given

terrain – nobody is beating down on Inside

Llewyn Davis because Rambling Jack Elliot is nowhere to be found, or that that

the narrative figure of Davis is not precisely Dave Van Ronk.³ But history is

dense & polyvalent in way that even the Coen Brothers wouldn’t attempt on

screen, and this trio of films will work better for people with little or no

understanding of the period than for anyone who has spent a little time with

the books (let alone with the poets themselves).

¹ Only

Markey, Rifkin & Netesky portrayed Ginsberg while he was still alive – the

other 16 portrayals have all been in the last 15 years.

²

Anyone who has seen Adams in American

Hustle has already seen one of the great acting performances of the past

decade.

³ To

be fair, there are figures in Bob Dylan’s memoir Chronicles who are considerably more fictive than, say, the Justin

Timberlake-Carey Mulligan version of Ian and Sylvia Tyson under the characters

of “Jim and Jean.”