In 1968, Ed van Aelstyn, my

linguistics professor at San Francisco State & co-founder of Coyote’s Journal, my favorite poetry mag

of the mid-1960s, persuaded me that if I was serious about my poetry I ought to

attempt a journal of my own. So, after the strike at State caused every

untenured faculty member I respected at the school (including van Aelstyn) to

quit or be fired, I dropped out, took a few classes at Merritt College (still

in those days in the flatlands of North Oakland) to get the units I needed to

transfer to Berkeley and, with the aid of d alexander, sent letters to every

poet I was interested in asking for work, getting responses and/or sparking

correspondences with Robert Kelly, Larry Eigner, Daphne Marlatt, Clayton

Eshleman, Jerome Rothenberg, Armand Schwerner et al. And then I did … nothing.

Which was exactly what I knew about publishing a magazine. I had no clue

whatsoever, no money – one could live easily enough on $150 a month in those

days, but that didn’t leave one much in the way of disposable income – and seemingly

no social skills that would have led me to actually ask somebody who knew more

about this process than I. Gradually, the thermometer-like guilt meter began to

rise, but once I got accepted into UC, embroiled in David Melnick’s attempt to

get post-New American poets like David Shapiro & David Bromige into the

campus literary journal Occident &

a subsequent project with Melnick to get a portfolio of Bay Area poets into the

Chicago Review, the idea of a journal

of my own slipped further & further from my consciousness. Then there was

Kent State & I found myself among a handful of undergraduates on the

steering committee of the Wheeler Action Committee – as the English Department reconstituted

as an anti-war project called itself – running a silkscreen workshop in the

grad student carrels to support other anti-war groups, climbing out David

Henderson’s window to hang the Harriet Tubman Hall banner from the Wheeler

balconies, putting in 20-hour days and starting to acquire those aforementioned

absent social skills. After the end of that semester, Shelley & I moved to

Buffalo briefly, then Trumansburg, & then back to Berkeley where I won my

six-year battle with the draft board & we finally called it a day on our

five years of marriage.

So, it was in the fall of

1970, while I was living in a dilapidated backyard cottage on 61st

Street in North Oakland that I got an unsolicited submission from a San

Francisco poet I’d never even heard of named David Gitin. The long repressed

guilt thermometer instantly popped up, and was now close to boiling over, not

only because I had sat on all this poetry for so unconscionably long, but

because Gitin’s poetry was terrific. This was exactly what I had thought a

little magazine was supposed to accomplish – putting you in touch with great

new poets. While at Berkeley, I’d read all

of Pound’s correspondence in microfilm in the UC library & had realized

that his impact on modernism & beyond came about no so much because of his

own writing – tho I was (and still am) a fan of The Cantos – but because he saw it as his duty to put A in touch

with B, X in touch with Y. Somehow I had accomplished this, albeit on an

infinitely smaller scale, with my little non-existent journal just by wanting

it to be so.

This was the poem that first

made the hair on the back of my neck stand up. Its title simply is Poem:

birds

color the sky

beyond the door

color the sky

beyond the door

the stone

lions

lions

the museum

parkinglot

parkinglot

I could see, of course, the

heritage of imagism and objectivism in those lines, plus the accentuated

concreteness of imagery. If it reminded me of George Oppen’s work, it was the

Oppen of Discrete Series, the edges

of each image all but chiseled into marble. Running parking lot into a single word seemed exactly the right touch –

that absent en dash is at least part of the drama of the final line. That

somebody was paying such close attention was what I sought out in poems, and do

to this day.

So I wrote to David &

told him, yes, I would be happy to publish his work as soon as I figured out

how to do that. And I gathered up a few pages of the writing I’d collected,

typed them up, hand-drew a logo for my instantly renamed new project &

headed down Telegraph Avenue to a copy shop where I printed the first issue of Tottel’s. I didn’t

get David’s poems

into the journal until the next issue, although I would go on to devote the

entire seventh

issue of the journal to his work. It was the third single-author

issue of Tottel’s, following ones by

Rae Armantrout & Robert Grenier, and preceding ones by Thomas Meyer, Clark

Coolidge, David Melnick & Larry Eigner. I still consider David’s work very

much on a par with that list of poets, which readers of this blog will

recognize as pretty close to ground zero for my aesthetic choices to this day.¹

David, once I met him, was a tall quiet man with a

ready laugh & whose intensity was somewhat hidden by a deep shyness. He

gave me my first solo reading ever at a bookstore around the corner from the former Hotel Wentley & later

would also give me my first campus reading as well once he began to teach down in

Monterey. I recall taking him to see a midnight show by the Cockettes in North

Beach, a side of San Francisco culture that straight men were just starting to

adjust to in those pre-Harvey Milk years. His path to poetry had been an unusual one,

picking the University of Buffalo not because Creeley & Olson taught there,

but because it was his hometown state college (a path that Lisa Jarnot would

replicate a few years later). How he got to San Francisco I’m not quite

certain, but he and his first wife Maria soon moved south and David’s already

encyclopedic knowledge of jazz and world music became an even deeper focus for

him as he pulled back from his engagement with “the scene” aspect of poetry. I

recall sometime in the 1970s telling him of the death of Paul Blackburn years

before and being shocked that he hadn’t heard, given that he’d been one of the

closest readers of Blackburn I’d known. When I was putting together In the American Tree in 1981-2, David’s

position was that poetry was “over” for him, he wasn’t writing or sending work

out, and that it made no sense to think about him for the anthology.

Happily, that was only partly true – he was writing,

but had no real interest in engaging with what he took to be a thoroughly corrupting

publishing scene, and for much of the rest of his life he would craft these

small, utterly gorgeous chapbooks of his writing – a tradition that readers of

John Martone and Tinker Greene will surely recognize – and send them to

friends. I read every word of each one, even as many contained poems I might

have seen before, or even recycled book titles (Journey in 1997, The Journey

Home in 2010). In addition, he would let publishers he trusted – George Mattingly

or his former student Dan Linehan – bring out somewhat larger collections. Woke Up This Morning, a 119-page

selection of 52 years of work, came out earlier this year, self-published but

with a Mattingly design.²

Like Lorine Niedecker, Alfred Starr Hamilton, NH

Pritchard, Besmilr Brigham or even Curtis Faville (who reviewed Woke Up This Morning here),

David Gitin was an American original, whose commitment to poetry was something

quite apart from any commitment to the poetry scene. His devotion to getting

the right word onto the page was absolute, leaving no room for sentiment,

foggy-headedness or any other manner of blur.

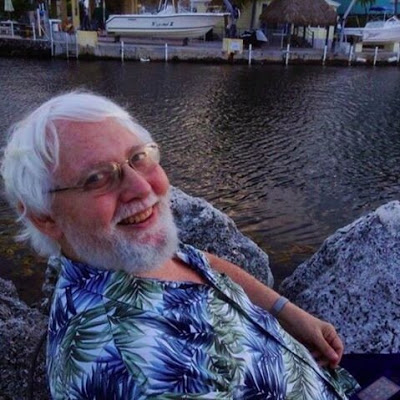

Getting his books & the occasional card or email, I

was able to follow David at a distance and like several of his friends, was

pleased and not a little amazed when he declared that he’d reconnected with his

high school sweetheart Gloria

Avner

and was heading to the Florida Keys to spend the rest of his life with her. Which

he did, passing finally late last month.

While Woke Up

This Morning must represent the poems David wanted saved, there are in his

other books enough great poems to warrant a volume twice that size, possibly

more. In addition to the early pieces you can find online in Tottel’s, Michael McClure has posted several

on his website, you can find a few in Big Bridge,

and you can find virtually everything on

Abebooks.com. One in particular that I like a lot is “Words,” which

I’ve always imagined as a sequel of sorts to that first poem of David’s that I

read in 1970:

I leap

from museums

onto passing cars

from museums

onto passing cars

¹ Too white & too male, I am well aware.

² Woke

Up One Morning was published in 1996 and contains untitled what is now

the title poem of this final volume.