Paul Blackburn and Me

Edie Jarolim

It’s been thirty years

since I finished editing the Collected Poems of Paul Blackburn. I still can’t

quit him.

Paul Blackburn died on September 13, 1971 — exactly

forty-five years ago today. He was forty-four. I never met him, but I spent

more than half a decade with him, writing my dissertation and editing his

collected and selected poems. When I started this three-pronged project, it

seemed to me that Blackburn had lived a reasonably long life. By the time I

finished, I thought he’d died tragically young.

As they say on Facebook, it’s complicated. Bear with me

here. I never wrote down this story before, so I’m relishing the details.

***

I first encountered Blackburn in the late 1970s through M.L.

Rosenthal, whose Yeats seminar I had taken as a grad student at NYU. I’d been

contemplating writing a thesis about one of the confessional poets, Rosenthal’s

specialty, but when I went in to talk to him about possible dissertation subjects,

Rosenthal said, “What do you think about Paul Blackburn?”

I hadn’t thought about him at all. I’d never heard of him. Rosenthal

explained, “Blackburn’s widow asked me to edit his collected poems. I don’t

have the time but I told her I would pass the job along to a qualified graduate

student.” He added, “If you do the scholarly edition for your dissertation, you’ll

end up with a published book when you get your Ph.D.”

I got hold of The

Cities, the book Rosenthal had recommended as quintessential Blackburn. Many

of the poems were about the BMT subway line, which I’d grown up riding in

Brooklyn. I admired Blackburn’s technical skill, his musical score-like

notations of the works, his ability to make the writing look easy. I shoved down

my doubts about his attitudes towards women. A published book... Now there was

a shiny object for an aspiring academic.

The project turned out to be far more complex than I’d

anticipated. First, I had to come up with a criterion for inclusion in the

edition. I opted for poems that had been previously published. But what

constituted publication? A lot of Blackburn poems appeared only in mimeographed

editions. Should those be included?

I next had to decide on an organization. Should the poems

appear in the same groupings as the published volumes? There was too much overlap,

and many poems were published in poetry journals but not books.

My choice of a chronological arrangement led to other

questions: Should the date be based on the first draft of the poem or the

published version? And how would I determine the first draft date? And if

Blackburn revised the poem after it was published, which version should I use?

I became a poetry detective, interviewing ex-wives and

friends, identifying typewriters, tracking down biographical clues in the poems

(luckily there were a lot of those). The process was fascinating, but time

consuming. It didn’t help my efficiency that I was commuting between New York

and San Diego, where Blackburn’s widow, Joan, had sold his papers to UCSD’s

Archive for New Poetry.

San Diego – now there was another shiny object. A typical

Easterner, I went there expecting to find a smaller version of Los Angles. The

freeways were there, and also some of the congestion, but so was a seascape of

surprisingly pristine beauty, and a string of coastal cities, each with their

own distinct character. USCD resided in the poshest —and probably most stunning

— of them all, La Jolla.

I was hired to catalogue Blackburn’s archive and thus was often

on the scene for the groundbreaking reading series created by poet Michael

Davidson, the Archive for New Poetry’s director. I became part of the inner

circle of the graduate students and young academics in the UCSD literature

department. I also got friendly with the local writers in town (Rae Armantrout

and Jerome Rothenberg, for example), as well as visiting writers like Lydia

Davis and Ron Silliman. By no means was this project all work and no play.

I never quite pinned down how I felt about Blackburn’s

poetry, but after a while it didn’t matter. The editing was an end in itself

and Paul Blackburn was part of my life, day and night. He haunted my dreams.

Sometimes the scenarios were sexual, sometimes as everyday as my kitchen

cabinets. Kind of like his poetry.

Finally, I had a scholarly edition of 623 poems. For each, I

detailed the decisions that went into the editing and dating. I added a

critical introduction of maybe 50 pages, discussing Blackburn’s biography and

his place in the poetry pantheon as well as the editing theory.

Seemed like a wrap to me.

The powers that be at NYU disagreed. Now that his oeuvre had

been established – by me! – they argued that I had a basis for a “real” dissertation, a 200-page critical introduction

about Blackburn himself, rather than about the editing process. Who says irony

is dead?

When I finished this next Sisyphean task, I brought eight volumes

into the office of the recorder at NYU. She said, “You’re only supposed to

bring in two copies of your dissertation.”

“That is two

copies,” I said.

I’d had it with academia by then. It wasn’t just the hoops

I’d had to jump through at NYU. By the time I took my qualifying exams, my prose

style had been pulverized; I had the sentence structure of Henry James and the

verbal clarity of Yogi Berra. A decade earlier, I was writing college papers

praised for their lucidity. Next thing I knew, I was submitting a proposal for

a dissertation titled “From Apocalypse to Entropy: An Eschatological Study of

the American Novel.” I switched thesis topics and advisors but didn’t kick the

jargon and passive construction habits.

Which was a problem, because what I really wanted to be was

a writer, not a literary critic.

My not so-brilliant career plan had been to get tenure and

then, in my spare time, devote myself to my craft, in whatever genre that

turned out to be. Being a teaching

assistant at NYU had cured me of any desire to teach, which I realized would be

the main part of my job description. And that published book that was going to

help me secure my place in academia? It wasn’t going to do the trick or even

come close. Paul Blackburn, I now understood, was a “dead white guy,”

academia-speak for someone representing the establishment. My untrendy

specialty would consign me to the boonies before I could—maybe, possibly, who

knows? — snag a job in a decent city.

Nor did I want to give up my Greenwich Village apartment.

I grew up in Brooklyn and had finally acquired what every

bridge-and-tunnel brat aspired to in the days before the boroughs became hip: a

rent-stabilized place in Manhattan. Call me crazy, but I didn’t want to move

someplace I didn’t want to live to do something I didn’t want to do.

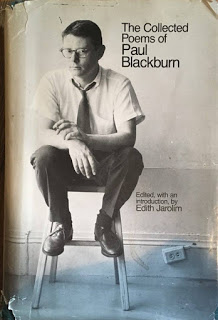

I helped with the publication of the Collected Poems by Persea Press in 1985. I tackled the Selected Poems next. Somewhere in

between there were small Blackburn books – The

Parallel Voyages, The Lost Journals

– and a few journal articles.

Slowly but surely I opted out of my role as the keeper of

the Blackburn flame, handmaiden to his reputation — and as a potential academic.

First, I happened into a job as a guidebook editor at the

travel division of Simon and Schuster. It took two more travel publishing jobs

and a move to Tucson in 1992 to finally jumpstart my long-delayed writing career.

This time, I had fewer qualms about leaving New York.

***

My retreat from all things Blackburn continued until 9/11. My

niece had phoned from San Antonio to make sure I was okay; though I was living

in Tucson, I often visited New York and my old digs in lower Manhattan.

Talk about wake up calls. Suppose I were to die suddenly –

and intestate? I was divorced, had no children, and my parents were no longer

alive. Everything would have gone by default to my older sister, from whom I

was estranged. I didn’t have much of an estate, except my literal estate. I

loved the swirled stucco home near the University of Arizona that I had bought for

a song – and I still loved literature. I decided to will my house to the UA’s

excellent Poetry Center, where it would be a residence for visiting writers. It

would be named for Paul Blackburn.

More time passed. My writing career thrived, though it was

diffuse. I authored three guidebooks, published hundreds of travel articles, became

a restaurant reviewer, wrote a dog book, became a dog blogger, discovered that

my great uncle’s butcher shop in Vienna had been in the same building as

Sigmund Freud and became a genealogy blogger [www.freudsbutcher.com].

One day, maybe two years ago, a friend tagged me on

Facebook to join a poetry discussion about Paul Blackburn. It was like

attending my own funeral. One of the participants wondered what had happened to

me. Another chimed in, authoritatively, that I had “become a professional dog

person.” Clearly, my dog blog had better SEO than my genealogy blog.

This public erasure of my career between the Blackburn years

and the publication of my dog book was one of the many things that inspired me

to finish a memoir that had been on the back burner for about a decade, called Getting Naked for Money. Traditional

publishing had by now hit the skids and I wanted more control over my work and,

especially, over my royalties. I started a Kickstarter campaign to raise money

to publish it myself.

It was through that campaign and reconnecting with old

friends from my poetry past that I discovered there had been a combined

celebration of the digitizing of Paul Blackburn’s archive at UCSD/surprise retirement

party for Michael Davidson—to which I hadn’t been invited. Well, fuck. Now even

that accomplishment had been erased.

I thought about my bequest to the UA. Why was I still holding

on to any connection to Paul Blackburn? Others around me had clearly moved on,

abnegating my role. I still wanted to will my house to the university as a

writer’s residence, but now, I decided, it would be reserved for women over 50

writing in any genre. Women that the world tended to ignore, in spite of the

good work they were doing.

I contacted the UA and said I’d like to change the terms of my

bequest.

This was about a month ago. Here’s where the story gets really

weird.

At around the same time, I had dinner with a woman whose

acquaintance I had made earlier this year at a Seder, another single ex-New

Yorker. I started telling her about changing my bequest to the UA. She

interrupted me mid-sentence. “Did you say Paul Blackburn?” she practically

shouted.

Yes, I said, Paul Blackburn. I thought she was confused.

Blackburn had always been a poet’s poet. In my experience, the publication of

the Collected Poems and Selected Poems hadn’t done much to widen

his reputation.

She knew exactly whom I meant. Paul Blackburn had been her

first lover. She had been 17; he had been in his mid-thirties and married to

his second wife, Sara. They saw each other for about a year. She eventually left

New York and married someone else but always thought, somehow, that Paul would

turn up in her town, maybe to give a reading. She was shocked to learn that he

died, about a year after the fact.

She sent me pictures that she and Paul had taken in a photo

booth, he preserved in amber with a little goatee, she in a fresh-faced

youthful incarnation that was equally mythical to me.

I wasn’t surprised at the revelation of the affair; his

poetry had always hinted at infidelities. I was saddened because I’d liked Sara

Blackburn the few brief times I’d met her, but I was hardly one to judge. Mostly,

I was appalled at the age — and power —difference. As my friend said, if it was

today, he might have been charged with statutory rape by her parents.

I felt like I was in a weird time loop, doomed to relive a

past that was no longer relevant to my present over and over.

But the incident sent me back to The Collected Poems. I looked at my introduction. Apparently,

graduate school hadn’t robbed me of all lucidity after all, though I’d had to

work harder to achieve it. And I realized, again, that what I thought and think

about the poetry makes little difference. The collection exists, beautifully

presented by Persea, painstakingly edited by me. It brought pleasure to Blackburn’s many

admirers. That’s no small accomplishment to claim.

And, I figured, if you can’t escape your past, you can share

your version of it – with a little help from your friends.

Shameless self-promotion for Edie Jarolim: The Missing

Years. My memoir, Getting Naked for Money: An Accidental

Travel Writer Reveals All will be out in a couple of weeks.

Subscribe to my blog, http://www.ediejarolim.com/

for updates – and for outtakes, emailed only to subscribers. Some pretty

fun stuff fell on the cutting room floor.