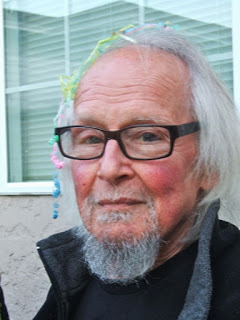

David Meltzer

1937 - 2016

1937 - 2016

Here is a note I wrote on David's work here in 2005.

I’ve

written on numerous occasions that the so-called San Francisco

Renaissance was largely a fiction, perpetrated in part by Donald Allen

in order to give The New American Poetry a

section that acknowledged just how much of this phenomenon rose up out

of the San Francisco Bay Area – a literary backwater prior to WW2, but

now suddenly a primary locale for much that was new. The other part –

and it’s not clear to me who, if anyone, could be said to have

perpetrated this – was an allusion back to the earlier Berkeley

Renaissance, which had been a decisive, thriving literary tendency in

the late 1940s, early 1950s. If you look at Allen’s S.F. Renaissance

grouping, you call still make out the vestiges of that earlier moment in

the presence of Robert Duncan, Jack Spicer & Robin Blaser, the

trio that had given rise to the Berkeley Renaissance while studying at

the University of California, along with, I suppose, Helen Adam, who at

the time of the anthology was something of a Duncan protégé. Yet there

are also poets representing an older San Francisco scene, such as

Madeline Gleason & James Broughton & even – tho it’s a

stretch, given what a loner he was, at least when he wasn’t actively

channeling Robinson Jeffers – Brother Antoninus (William Everson). Then

there are a group of younger poets – Richard Duerden, Kirby Doyle, Ebbe

Borregaard & Bruce Boyd – whom it’s harder to place

aesthetically, a fact that is still true some 45 years after the book’s

initial publication, as they’ve become its

least published participants. That Allen placed Lawrence Ferlinghetti

into this grouping, rather than with the Beats, suggests just how

arbitrary these distinctions were.

Given

that he was improvising & fabricating in search of clustering

principles in general, it’s curious that Allen completely missed one of

the most interesting & useful formations among the New

Americans, a western poetics that may have first revealed itself at Reed

College in Portland, and which didn’t fully take flight until the mid-

to late-1950s in San Francisco. Gary Snyder, Lew Welch & Phil

Whalen in fact were just the first of a number of poets who came out of

this aesthetic – one could probably put Duerden & Borregaard

there as well, plus three other contributors to the Allen anthology, all

of whom joined Snyder & Whalen in Allen’s curiously amorphous

unaffiliated fifth grouping: Michael McClure, Ron Loewinsohn &

David Meltzer. Beyond the Allen anthology itself, one might add Richard

Brautigan, James Koller, Joanne Kyger, David Schaff, Bill Deemer, Drummond Hadley, Clifford Burke, David Gitin, John Oliver Simon, Lowell Levant, John Brandi, Gail Dusenberry

& a host of others. In general, these poets were straight where

the Duncan-Spicer axis was gay. Perhaps most importantly, this cluster

really had no leaders as such. It was not as though some, such as Snyder

or Whalen, might not have led by example, but that their personalities

were not given to the constant marshalling of opinion that one could

identify in such others as Olson, Duncan, Spicer, Ginsberg, O’Hara or

even Creeley. This mode – lets call it New Western – perhaps reached its

pinnacle of influence during the heyday of Jim Koller’s Coyote’s Journal during

the mid-1960s. But without anything like a leader or a program, poised

midway aesthetically between the Beats & Olson’s vision

of Projectivist Verse, the phenomenon never gelled, never became A

Thing & by the 1970s already was entering into an entropic

period from which it has yet to re-emerge.

Just 23 when The New American Poetry hit

the streets, Ron Loewinsohn & David Meltzer were the babies of

that project (indeed, they’re just one year older than David Bromige

& David Melnick & eight years younger than Hannah

Weiner, all of whom would be associated more closely with language

writing come the 1970s). Loewinsohn went on to become a literature

professor & novelist, but Meltzer has hung in as a poet, with a

few side forays into music, jazz writing & erotic fiction, all

these decades. Now, with David’s Copy just out from Penguin, Meltzer seemed poised to get the attention his work is due.

Actually,

considering just how many of the Beat poets were treated like rock

stars while Meltzer, fronting Serpent Power with his late wife Tina (and

drums by Clark Coolidge), actually had a rock band long before Jim

Carroll or Patti Smith, it’s odd that Meltzer hasn’t become much more

widely known, celebrated before this. David’s Copy is at least the fourth selected poems he’s published, the others being Tens, Arrows & The Name, and

many of his earlier books were published by Black Sparrow, one of the

rare small presses to have had some volumes – mostly those by Charles

Bukowski – widely distributed through the big book chains.

There

are, I suspect, multiple reasons for this. One is that New Western

aesthetic never really broke through, even if a few of its practitioners

– Whalen, Snyder, McClure – did. A second, more important aspect is

that old bugaboo of so many poets – Meltzer’s not a compulsive

self-promoter. As the youngest of the New Americans, his timing was just

a little behind from a marketing perspective. Indeed, as Ginsberg et al

became folk icons in the 1960s, Meltzer’s first books that decade were

from small Bay Area fine presses like Auerhahn & Oyez – his one

big trade publication prior to David’s Copy being an anthology he edited in 1971, The San Francisco Poets, a

collection notably missing the Duncan/Spicer axis, including just

Ferlinghetti, Rexroth, Welch, McClure, Brautigan & Everson.

Meltzer’s first sizeable collection doesn’t appear until 1969, when he

brings out Yesod with

the British press, Trigram. It didn’t receive much distribution

stateside. Black Sparrow releases his first large collection in the

states, Luna, in 1970.

Part

of this neglect may also be due to the fact that Meltzer is Jewish.

It’s not that there were no Jews among the New Americans – Ginsberg, Orlovsky, Eigner

all come instantly to mind. But the intersection between the New

American poetry & the New Age approach to religious experience

in the 1960s (Serpent Power?) tended to mute its presence in all but

Ginsberg’s writing. Indeed, I wouldn’t be at all shocked to discover

that many readers of Eigner were late to discover the heritage of the

bard of Swampscott. In the 1960s, the Objectivists were only gradually

coming back into print. And Jerome Rothenberg didn’t really begin making

the space for an active presence for a Jewish space within American

poetics until late in that decade, during that interregnum betwixt the

New Americans & language poetry.

Finally,

Meltzer – and this I think is a sign of his youth relative, say, to

Whalen or Snyder or Ginsberg or Olson or Duncan or O’Hara et al – lacked

the kind of visible trademark of a differentiated literary style that

one associates with all of the above, and even with someone closer to

Meltzer’s age, like Michael McClure. Meltzer’s work has always been in

the vicinity of New American poetics without ever being its own

recognizable brand – as such, it would be difficult if not impossible

for a younger poet to mimic. It’s not that Meltzer lacked the chops

& more as though he never saw the need per se. In this sense,

Meltzer’s situation is not unlike that, say, of a Jack Collom, another

terrific poet of roughly the same generation who has never really gotten

the recognition he deserves. In a sense, those who were a little

further outside the New American circle – like poets in New York who

were visibly not NY

School, such as Rothenberg, Antin, Ed Sanders or Joel Oppenheimer – had

an advantage because their circumstance forced them to define

themselves in opposition even to poets whose work they cherished.

Indeed,

if there is a defining element or signature device in Meltzer’s work,

it’s that he alone among the New Westerns has an eye for the hard edges

of pop culture, something one expects from the NY School. Often, as in

this passage from “Hollywood Poems,” it’s accompanied by a tremendously

agile ear:

De Chirico without Cheracol

saw space where its dead echo opened up

a plain unbroken by the dancers.

Instead

a relic supermarket nobody shops at.

Plaster-of-Paris bust of Augustus

Claude Rains Caesar face-down beneath

a Keinholz table

whose top is blue with Shirley Temple’s saucers,

pitchers. Mickey Mouse

wind-up dolls in rows like Detroit.

All tilt out of the running without electricity.

Veils of history,

garments worn in movies, hung on

steel racks at Costume R.K.O.

R. Karo would’ve used the tower’s light.

He’d wear it as a cap to re-route lost energy.

saw space where its dead echo opened up

a plain unbroken by the dancers.

Instead

a relic supermarket nobody shops at.

Plaster-of-Paris bust of Augustus

Claude Rains Caesar face-down beneath

a Keinholz table

whose top is blue with Shirley Temple’s saucers,

pitchers. Mickey Mouse

wind-up dolls in rows like Detroit.

All tilt out of the running without electricity.

Veils of history,

garments worn in movies, hung on

steel racks at Costume R.K.O.

R. Karo would’ve used the tower’s light.

He’d wear it as a cap to re-route lost energy.

So dense with details that it rides like a list (& sounds

like a Clark Coolidge poem), this passage is actually a better

depiction of a De Chirico landscape than those one finds in John

Ashbery’s poetry. David’s Copy is filled with such moments, which makes it a terrific read.

One

might squabble with the fact that the book is not strictly

chronological, or that the first 25 years of his writing gets more

weight (over 150 pages) than does the last 25 (roughly 100), tho I

suspect that’s because more of the recent work is still in print. On the

whole, such squabbles are few. Editor Michael Rothenberg had done a

first-rate job here, smartly including bibliography & a decent

two-page bio note from Meltzer & an excellent introduction from

Jerry Rothenberg. Toward the end of the introduction, Rothenberg notes:

Elsewhere, in speaking about himself, he tells us that when he was very young, he wanted to write a long poem called The History of Everything. It

was an ambition shared, maybe unknowingly, with a number of other young

poets – the sense of what Clayton Eshleman called “a poetry that

attempts to become responsible for all the poet knows about himself and

his world.” Then as now it ran into a contrary directive: to think small

or to write in ignorance of what had come before or in deference to

critic-masters who were themselves, most often, nonpractitioners & nonseekers.

From

my perspective, it’s a shame that project never took hold, but then I

don’t think there’s any contradiction between such scale & the

desire to “think small” (or, as I might put it, to write in the present)

– that’s one lesson one takes from Zukofsky’s “A.” Throughout,

there are works that evidence an impulse to “go long,” almost in the

sense of a football quarterback, but most often they come back to the

compilation of shorter works that one might expect to see from the likes

of Whalen, Welch or Snyder. The whole of David’s Copy offers us a deeper link into that New Western poetics, even as it connects that world outward, toward the New York School & the poetics that would emerge in the 1970s & ‘80s in a journal like Sulfur. The

key, as it is in New Western poetry in general, is precisely that

desire to “think small” as Rothenberg puts it, to write in the complete

present. Meltzer is less openly Zen-like than, say, Whalen or Joanne

Kyger, but the pleasure can be every bit as deep.