Ben Friedlander jokingly introduced

me at the 2017 National Poetry Foundation conference on the poetries of the

1990s by saying that that decade had been “the period between language poetry

and Silliman’s Blog.” Later, in one of those hallway conversations that proves

so fruitful at events like this, Ben and I talked more seriously about how one would periodize language writing, if one

wished to do so. It’s a little like asking if Beat poetry still exists today,

given that Michael McClure, Gary Snyder and Lawrence Ferlinghetti are still

active. I said at the time that I had been serious in my characterization of it

in the introduction to In the American

Tree as more of a moment than a movement.

But I had betrayed that assertion

in how I had edited that collection, including only those who had appeared

enough times in works by publishers and magazines so thoroughly associated with

langpo to thoroughly bear its stamp. And, as I’ve stated a few times since

then, I did so thoroughly enough that there were just three poets who fit my

criteria whom I failed to include: Curtis Faville, David Gitin and Abigail

Child. The first two had withdrawn from publishing by 1981-2, the period when I

put that book together, and I had misread Child as a committed filmmaker who

wrote much as she also danced and did performance art, a misreading on my part

that I have regretted ever since. If I had really edited that volume to

articulate the moment, I should have included first-rate writers who were quite

critical of language writing, such as Beverly Dahlen and Leslie Scalapino, or

who were off doing their own thing without much if any reference to what was

taking place at the Grand Piano, the Tassajara Bakery or the fledgling Ear Inn

readings. This would have included people openly hostile to some of langpo’s

investigations into language itself, such as Darrell Gray or Andrei Codrescu,

but it also would have included the likes of Norman Fischer, CD Wright, Joan Retallack,

Doug Lang, Phyllis Rosenzweig, Joseph Ceravolo, Judy Grahn, Michael Lally, Lorenzo

Thomas, Jim Brody, Simon Ortiz, and Nathaniel Mackey. Edited by a white guy on

the West Coast, In the American Tree is

very much a(n imperfect) record of a movement and not a moment at all.

Plus a nearly five-year gap

occurred between editing and publication, the result of the original publisher,

Ross Erickson Books, struggling financially. Had the collection actually been

edited close to its publication date, younger writers who had subsequently

emerged, including Charles Alexander, Laura Moriarty, Ted Pearson and Harryette

Mullen, surely would have been added to what was already an unwieldy number. In

1986, when the National Poetry Foundation finally got the 1982 manuscript into

print, Tree already some of the same

time-bound features I had noticed earlier in Donald M Allen’s The New American Poetry, which presents

the early Jack Spicer and not the later writer whom we think of today, the

Edward Dorn who is clearly a lyric student from Black Mountain, not the pop-art

philosopher-poet with the problematic politics. Indeed, Amiri Baraka was not

yet Amiri Baraka when he appeared in the Allen anthology. One could argue the

same for Denise Levertov as well.

Standing in the hallway in Orono, I

told Ben that if I had to do so, I would agree that language poetry was not a

literature of the 1990s, and that the poetics of the New Coast Conference, held

in March of 1990 and later gathered into a double anthology by the journal O•blēk, had in fact accomplished what

it set out to do, which was to announce a generational shift to a younger cohort

of poets, a group notably more diverse in race and gender than that figured

just four years before by Tree. The O•blēk anthologies never got the

distribution they deserved, and, perhaps because of the hostility by many of

the participants of the poetry publication to assertions given prominence in

the theoretical one[i],

the collections have never been republished or brought out in book form.

I also had already given langpo a

starting date, the appearance of Robert Grenier’s essay “On Speech” in the

inaugural issue of This in 1971. Even

48 years later, that still feels right to me. There certainly were earlier

manifestations of what would come to be known as language writing in journals

such as joglars edited by Clark

Coolidge and Michael Palmer (dating back as far as 1963, when Charles Bernstein

would have been just 12 years old, Erica Hunt only eight), 0 to 9, edited by Bernadette Mayer with Vito Acconci, and even my

own Tottel’s, which beat This into print by a matter of weeks. But

Grenier’s epic overstatement, “l HATE SPEECH,” had the concentrated effect of

an announcement every bit as much as Allen Ginsberg’s first reading of Howl in the Six Gallery, October 7,

1955, had announced the New American Poetry, no matter that it came five years after Olson’s essay on Projective Verse

and even after Black Mountain College itself had closed down.

Real life is messy like that. A

significant amount of the hostility to language poetry in the 1970s and ‘80s

came from poets like Codrescu and Tom Clark, who had been too young for The New American Poetry and yet felt

excluded by a younger map of the territory that no longer followed the familiar

terrain set forth by the Allen anthology.[ii] The O•blēk

anthologies suggested that the debate was already irrelevant. I think it’s

open to question whether I’ll Drown This Book: Conceptual Writing

by Women, edited by Caroline

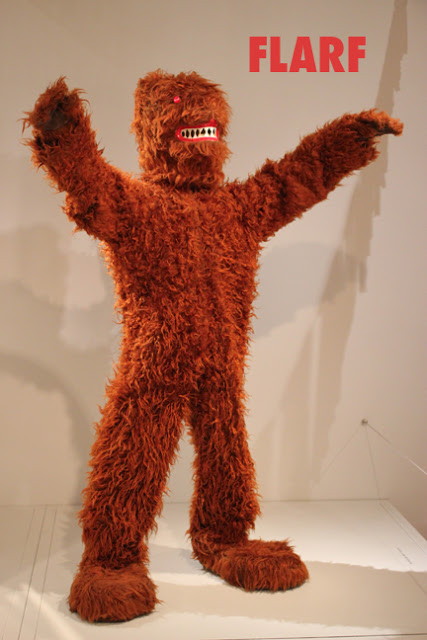

Bergvalle, Laynie Browne, Teresa Carmody & Vanessa Place, or Flarf: An Anthology of Flarf,

edited by Drew Gardner, Nada Gordon,

Sharon Mesmer, K. Silem Mohammad & Gary Sullivan – the current

pretenders to the short-lived Iron Throne of contemporary poetics – represents an

extension of the New Coast poetics put forward by O•blēk,

which is how I read them, or something altogether new. The documentary

conceptualism put forward by Chain was

clearly a part of the New Coast phenomenon and, nearing 20, flarf likewise is

long in the tooth, and if the cover of that anthology is any evidence, also in

need of a haircut.

What’s

next? as President Bartlett used to say back when the nation was governed

by the sane. The question of articulating any

movement of poetry in a world in which there exist some 50,000 publishing ones is one hell of a lot

harder than it was when the number was 2,000 or so just 30-plus years ago. Even

the neo-Edwardian strain still exists, although if Terrance Hayes and AE

Stallings are any evidence, they’ve had a serious rebirth of wonder since the

days of Lowell and Wilbur.[iii]

My concern is that without some

shape, younger poets have nothing to push against, no old guard conveniently

tottering and about to be tipped into the dustbin of history. The turn to

politics on the part of recent poets may be occasioned by how much more visible

the depredations of capital have become, but the difference between langpo and the poets of Chain was never a question of

political/non-political, but closer to which

political and how. You can’t say

that Terrance Hayes isn’t writing politically, even if his sense of caesura can

be breathtaking. I was a member of the Democratic Socialists of America on the

day when the New American Movement first merged with the Democratic Socialists’

Organizing Committee to form that organization and my membership is still current, thank you. As I’ve

tried to make clear here and on Facebook and Twitter, I think we’re all in this together.

But poetry is governed by seasons – what gave birth to

the New American Poetry was a hiatus occasioned by World War 2 when the number

of books being published in the US was curtailed by the cost of paper and ink,

and the absence of males from the continent. As it was, the number of books of

poetry published in the US shrank from around 100 per year to just half that until well

after the war. The old world had been an argument between the neo-Edwardians

led by the Benet brothers and Robert Frost[iv]

and the moderns led by Pound, Williams and the Objectivists. The publishing

world was aligned with the neo-Edwardians and thus, as a result of the war’s

impact on publishing, many Objectivists stayed out of print until the 1960s after the arrival of Ginsberg et al. Since

the New Americans, we really have had just two other generations of poetry,

albeit with much haziness at the margins.

It seems that we are now ripe for a third. From my

perspective (in the dustbin of history where we are making room for the

conceptualists and flarfists), I’m searching out for new shoots, wondering just

where they might take us all. I for one am ready for the ride.

[i] Basically that a lack of spirituality was a defining

feature of language poetry and that a return to religion would thus be a

hallmark of poetry going forward, two decidedly inaccurate claims.

[ii] Which was a notoriously untrustworthy map. The absence

of the Spicer circle was no doubt Duncan’s influence – Robert claimed that he

had told Allen whom to include – just as the fiction of a San Francisco

renaissance was his mechanism for getting older poets like James Broughton and Brother

Antoninus into the book. Allen’s pointed comment in the introduction about

Zukofsky’s exclusion suggests that a line was being drawn – Robert was allowed

to dictate the San Francisco scene, but not the whole shebang. The 1967 A Controversy of Poets anthology, where

Robert Kelly selected the New Americans and Paris Leary chose the

neo-Edwardians, includes Zukofsky.

[iii] The brief interregnum of the Gnu Formalism can best be

understood as an admission that the poetry wars, if not set off by the Allen

anthology at least marked by it, was thoroughly won by the New Americans. The

argument against this would basically be that the social upheavals of the 1960s

disrupted everyone, and that the

rejection of the New American paradigm by the likes of Dorn, Baraka and

Levertov were no greater than the turn away from rhyming pentameter by the likes of Bly, Merwin, Plath, Wright, Hall

et al. The curious thing, reading anthologies of the New Formalists, is the

near total absence of poets born in the 1930s. Hayes was born in 1971,

Stallings in 1968.

[iv] Between them, Frost and the Benet brothers had 7

Pulitzer prizes by the time Stephen died of an early heart attack in 1944,

including those for that year and the two preceding ones. Stephen also

controlled the Yale Younger Poets award, the only other prize in US poetry to

get significant critical and news coverage.