Multitudes

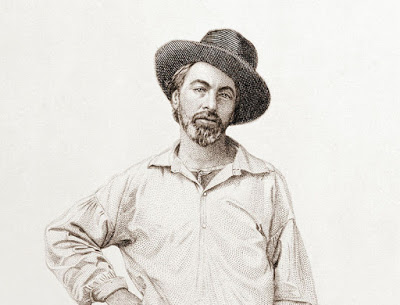

Walt Whitman often

is characterized as an apotheosis of the American cult of individualism with Song of Myself presented as exhibit A –

Stephen Mitchell, for example, writes

Certainly the poem embodies an outrageous

egotism, an “I” so shamelessly naked that even a bodhisattva can admire it[i],

but I hear something different. It

may be because I have been teaching Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons at the same time that I have been rereading Song, in Mitchell’s faux version of the

1855 first publication in Leaves of Grass

that presented the text as a single unbroken long poem, in a truer version

of the first edition[ii], and in the 1891 “deathbed” edition that

replicates the 1881 final variant, broken now into a suggestive 52 sections and

using a title that did not settle on the text until 1876. Song was published in six different compositional stages during

Whitman’s life, with Mitchell’s 1993 edition representing what he himself

characterizes as a “conflated version”.

Preparing my notes

on Stein’s prose poems, I’m reminded that while Whitman was dying in Camden, an

event reported on by the US press on a daily basis, the 17-year-old Stein[iii]

was in Baltimore preparing to attend Radcliffe and certainly was aware of

America’s most famous and thoroughly out gay poet. Matt Miller has written of

Whitman’s influence, for example, on The

Making of Americans[iv],

a title that fairly screams it out and whose scope recalls the ambition of Song if not the whole of Leaves of Grass. 43 years ago, G. Thomas

Couser observed that:

two of our most eccentric writers and

autobiographers – Walt Whitman and Gertrude Stein – seem to share many

intriguing similarities.[v]

True that. But where Couser locates

these similarities in time and identity, what I hear instead is a tic in number,

very nearly a drumbeat of the plural.

In the original

1855 edition, it jumps right out in the sixth line:

Houses and roof perfumes

. . . . the shelves are crowded with perfumes

By the deathbed version, two additional stanzas had been inserted into the poem, pushing this line into the second

section while converting Whitman’s four-period ellipsis into a comma, and

trading in roof for the rhyme of rooms, a revision that spells out the

primacy of sound in this text:

Houses and rooms are full

of perfumes, the shelves are crowded with perfumes

Rooms also has the advantage of being

plural. The number of multiples in just the first few pages of the poem are

stunning:

·

Echoes, ripples, and buzzed whispers

·

green leaves and dry leaves

·

darkcolored sea-rocks

·

belched words . . . . words

·

A few light kisses . . . . a few embraces . . .

. a reaching around of arms

That is a page-and-a-half from the

Mitchell. In addition to having composed a 50-page poem that favors exposition

over narrative, Whitman has written one

in love with the plural:

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I

contradict myself,

(I am large, I

contain multitudes.)

I concentrate toward them

that are nigh,

The conversion of roof to rooms is fortuitous, as Rooms

is the title of the third and final section of Tender Buttons, the chapter of Stein’s book that is not a series of

short, witty prose poems but very nearly an

essay (in Stein’s unique manner) on method. Buttons likewise concentrates “toward them that are nigh” as the

world it conveys is very much that of bourgeois women of pre-First World War

Paris, poem titles filled with hats, coats, umbrellas, and “a long dress,” with

relatively few references to men beyond soldiers and that “white hunter.”

Plurals categorize

right where creative writing workshops argue that one should focus on the

specific. In theory the singular is concrete, the plural general. It’s not an

accident that we target in on the wheelbarrow, sensing a softer, almost fuzzy

focus on the chickens. Yet as that shipwreck of the singular, George Oppen,

reminds us at the start of Of Being

Numerous,

There are things

We live among ‘and to see

them

Is to know ourselves’.

That is very much what Stein is

getting at with her invocation of familiars throughout Tender Buttons. And it is also what I hear throughout Song of Myself.

Whitman’s language

in this sense is the antithesis of Pound’s, whose preference is for specifics

drenched in historical & sometimes mythological connotation. Which also was

what Williams heard in The Waste Land:

Eliot returned us to the classroom just at

the moment when I felt we were on a point to escape to matters much closer to

the essence of a new art form itself – rooted in the locality which should give

it fruit[vi]

O stars of heaven,

O suns . . . . O grass of graves . . . . O perpetual transfers and promotions

O suns . . . . O grass of graves . . . . O perpetual transfers and promotions

Lists like this from the 49th

canto of the deathbed Song lack

Stein’s percussive alliteration, but, once stripped of the romantic “O,” the major

difference is between Stein’s invocation of an interior world, household

objects and food, over Whitman’s wider ranging, often more abstract or

“transcendental” categories. Whitman’s plurals can be concrete, as with the

twenty-eight young men observed splashing in the water in the 11th

section or the

Blacksmiths

with grimed and hairy chests […]

The

lithe sheer of their waists plays even with their massive arms

Overhand the hammers swing, overhand so slow, overhand so sure,

They do not hasten, each man hits in his place

Overhand the hammers swing, overhand so slow, overhand so sure,

They do not hasten, each man hits in his place

He’s closer here to Williams than Stein, employing the plural to set

up a close-up. Looking at the following famous stanza, you will see that even

the singular nouns other than “I,” categorize. They may be singulars but

they’re plurals at heart.

Patriarchs sit at supper with sons

and grandsons and great-grandsons around them,

In walls of adobie, in canvas tents,

rest hunters and trappers after their day’s sport,

The city sleeps and the country

sleeps,

The living sleep for their time, the

dead sleep for their time,

The old husband sleeps by his wife

and the young husband sleeps by his wife;

And these tend inward to me, and tend

outward to them,

And such as it is to be of these more

or less I am,

And of these and all I weave the song

of myself.

First presented at the Five Up on Walt pre-birthday celebration at Kelly Writers House, Feb. 5, 2019

[i] “Editor’s Preface,” Song of Myself, edited by Stephen Mitchell, Shambhala, Boulder,

2018, p. xi.

[ii]

Online in a Roslings Ditgital Publications PDF available from the Western

Illinois University website: http://faculty.wiu.edu/M-Cole/WaltWhitmanLeavesofGrass1855.pdf

[iii] The same age I was when William Carlos Williams died

in 1963. It was Williams who opened the door of poetry to me through his poem

“The Desert Music.”

[iv] Miller, “Making of Americans: Whitman and Stein’s

Poetics of Inclusion,” Arizona Quarterly,

Vol. 65, No. 3, Autumn 2009

[v] Couser, “Of Time and Identity: Walt Whitman and

Gertrude Stein as Autobiographers,” Texas

Studies in Literature and Language, vol. 17, no. 4, Winter 1976