M/E/A/N/I/N/G Online #1

Is Resistance Futile?

I feel resistance

is necessary no matter how quixotic the effort. Starting

M/E/A/N/I/N/G

in 1986 was an act of opposition to the stances embodied in much

of the theoretical positioning in the art magazines and artwork

of that time. A central feature of M/E/A/N/I/N/G was the

creation of a space in which feminist issues could be explored but

also in which male and female artists were given an opportunity

to address issues of concern to them. This created a dialogue between

the genders as well as establishing a zone for exploring further

aesthetic, political, and practical issues. I have also been a member

of A.I.R. Gallery

since 1996. A.I.R. was founded in 1973 and was the first women's

cooperative gallery in the U.S. It is also an active and ongoing

site of cultural and social resistance. In fact, my first appearance

on a panel—it was called "Critics: A New Generation"—was

at A.I.R in 1982, when the gallery was located on Crosby Street

in Soho. In 1973, very few women artists were exhibited in mainstream

galleries, so there was an urgent need for a space like A.I.R. to

exist.

Of course, resistance is not always successful. You may resist trends or assault them, but the art establishment lives on often blissfully unaware that any opposition has even occurred. Or perhaps it may notice that a tiny flea is nipping at its ankles but chooses to ignore the nuisance entirely. For instance, A.I.R. still has trouble getting its shows listed in the newspapers and several glossy art magazines do not review shows there. To some extent, the political ideas presented in M/E/A/N/I/N/G and in A.I.R. have been absorbed into the mainstream—feminism is a prime example—but only to be spit out in distorted forms, often without women attached.

|

|

Over the years, A.I.R has served as an important launching pad for some of today's best known women artists. In addition, throughout the 70s, 80s, and 90s, the gallery organized a remarkable series of exhibitions, panel discussion, and performances. Many of the women who showed at A.I.R., and some who also founded the gallery, such as Nancy Spero, Elaine Reichek, Mary Beth Edelson, and Dottie Attie, have gone on to have significant artworld careers, showing in upscale galleries and museums. Another A.I.R. artist, Ana Mendieta, achieved fame and notoriety after her tragic death in 1985. However, other women artists who showed here have totally disappeared from anyone's radar screen. The fine lines between success and failure, visibility and invisibility, resistance and assimilation are permeable.

Some people question

the need for exclusively women's institutions like A.I.R. Certainly,

there is the danger of ghettoizing female artists or of the damaging

perception that women-only galleries are second-rate. In addition,

A.I.R., in particular, faces a generational crisis: its membership

is aging, and it is difficult to attracting qualified and interesting

younger women. Younger women artists want to make it in the mainstream,

if possible, not languish on the fringes, or in the past, where

many think the feminist movement resides. Some of the pressure is

off too: circumstances have improved for younger women artists,

partly due to the intervention of galleries like A.I.R. Many more

opportunities exist for younger women artists to move straight into

the mainstream. All these issues swirl around the gallery, creating

difficulties. But then, the decision to follow a feminist path in

art has never been easy. Being political and announcing your difference

is not the most unproblematic way to proceed in the artworld. That's

what makes maintaining an openly feminist space, with self-declared

feminist artists in charge, a continuing challenge.

|

|

A.I.R.’s cooperative structure is based on the principles of participatory democracy, which makes it a dynamic site for the fiercely individualistic and demanding egos of the twenty or so member artists. To come to a group decision is often an arduous process: the lack of hierarchy provides both a frustrating and a stimulating layer of intrigue. Since A.I.R. has been around for almost 30 years, rules have been formulated to deal with many of the problems that arise. However, without a dealer controlling everything, the artists are in charge of the establishment—a situation that can be described as the hens having charge of the henhouse. And because A.I.R. is noncommercial, the artists have the freedom to choose what they want to exhibit on aesthetic grounds. So, despite all the problems involved with running a cooperative, I think it's important that A.I.R. exists, even considering some women artists have made significant inroads into the mainstream. We still need a place of our own. In September 2002, A.I.R. Gallery will move from Soho to Chelsea and continue to keep up with the changing times. Many artists aspire to assimilate and succeed within the imposed framework of the artworld. However, I have found that certain biases and stereotypes will hold you back despite your best efforts. This is especially true with the insidious nature of race, gender, and age biases. A few token artists from a given discriminated-against group will be given attention, while the rest languish on the sidelines. Friends of mine have been told by dealers that they will not visit the studios of artists over age 35. The face of discrimination is always changing; you can cure it or tone it down in one place only to have it resurface in another spot.

A major factor undermining

resistance is burn-out. After a while people and institutions get

tired. People fight and fall out with each other and the idealism

that started the whole enterprise turns sour, at least at times.

In addition, the endless struggle for grants and money makes running

any nonprofit organization frustrating. With rents and living expenses

so high, small nonprofits are having great trouble staying alive.

Mira and I received some very welcome grants from the NEA and NYSCA,

but we had no help with most practical aspects of running the magazine

and basically did all the work ourselves. Still, as artists, we

were used to that approach.

|

|

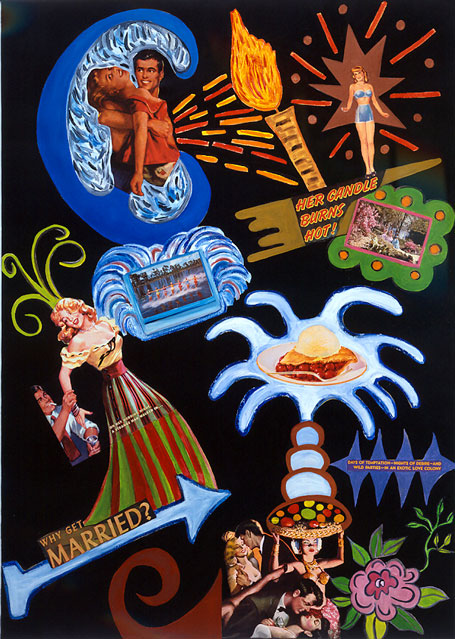

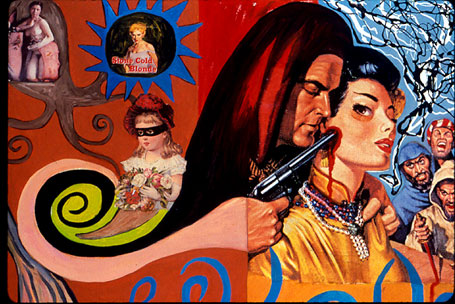

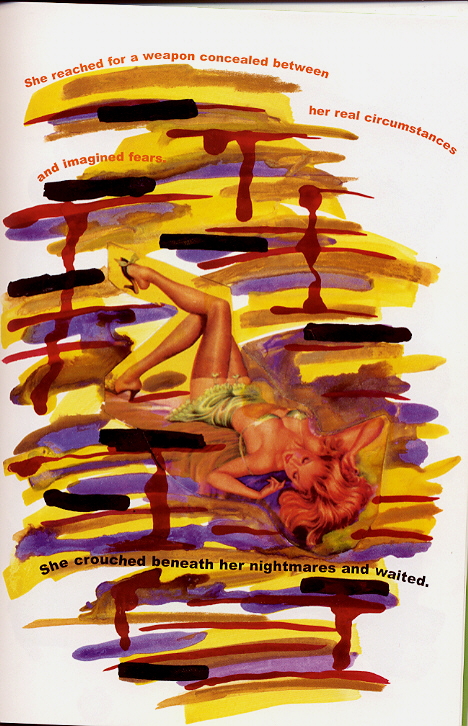

It is in my own artwork,

even beyond any experiences with alternative institutions, that

I have experienced marginality and otherness most directly. It feels

strange to nearly always be outside the trends. In the end, I find

I can't ignore the outside world but sometimes I have to proceed

as if I could care less about it. Art, for me, is a way of following

your own inner muse, while acknowledging the larger picture. No

matter how disturbingly at odds the two may be. That may mean pursuing

painting when it is considered outmoded. Or making artist’s

books and publishing collaborations with poets that have a very

limited audience and distribution networks. These books are often

ignored by both the art and literary mainstream since they fall

outside the norms for both fields. Above all, being an artist seems

to mean that one proceeds against the odds. The so-called spectacle

and the establishment will go on with or without me. I feel I always

have to grapple with that on some level in my work and in my life.

But, for sanity's sake, sometimes I just try to cocoon myself in

my work and do whatever I please. This leads to self-marginalization

and eccentricity, but pursuing my individual vision and aesthetics

is the reason I am an artist. I tend to admire those artists in

the past like William Blake, James Ensor, and Florine Stettheimer,

for instance, who went their own way.

|

|

ArtKrush is a great representative of the exciting new developments that really caught hold since 1996 when we stopped publishing M/E/A/N/I/N/G. It’s hard to believe that when we started our publication there was no internet and e-mail. I’m sure that if we were starting a journal right now, we would consider starting it up on the web. Beyond its commercial uses, the internet forms a potent basis for organization and resistance and allows for the creation of small groups of like-minded individuals who can band together for discussion and mutual support.

Establishing an alternative institution—be it a gallery space like A.I.R. or a journal like M/E/A/N/I/N/G or a web site like ArtKrush—creates a power base within which you can challenge authority. In the long run, these acts of resistance are more effective than resigning oneself to the status quo. And I believe every act of resistance is worth performing no matter how humble it is or how futile it may seem to be.

Susan Bee will show her paintings and her mother Miriam Laufer's paintings at A.I.R. Gallery in New York in February 2006. She has published six artist's books with Granary Books, including The Burning Babe and Other Poems with Jerome Rothenberg, Bed Hangings with Susan Howe, and A Girl's Life with Johanna Drucker. She is coeditor of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: An Anthology of Artist's Writings, Theory, and Criticism and teaches in the School of Visual Arts Graduate Program in Art Criticism and Writing. Her home page can be found here.

| Contents: |

Hi, My Name is Artwork |

Is Resistance Futile? |

Is Resistance Futile? |

Is Resistance Futile? |

The White List |

Have Billboards Changed the Meaning of Public Space in Poland? |