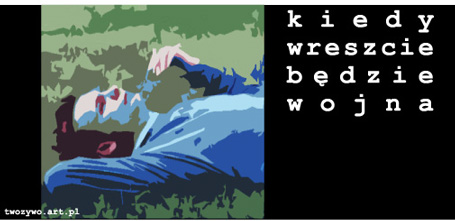

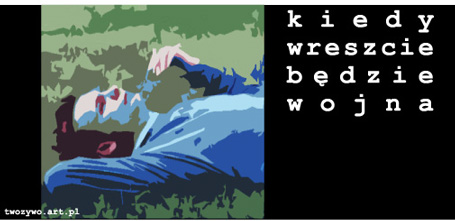

"When Is a War

Finally Going to Happen?" was the question posed to the Warsaw

public on September 8th last fall on a billboard that showed a picture

of a man lying down and gazing dreamily at the clouds. Three days

later, the authors, artists from the art group Twozywo (Art Mater/i/n/al)

covered the word "war" on this handmade billboard, changing

its meaning in Polish into "When Is It Finally Going to Happen?"

From the point of view of the management of Art Marketing Syndicate

S.A. (AMS) this artwork, originally addressing the laziness and

the thoughtlessness of the new consumerist society in Poland, had

become, in the recent political context, "too prophetic."

Indeed, it is not the first time that art on billboards sent a strong

message to the public in Poland. The activities of the Galeria Zewnetrzna

(Outdoor Gallery), an art project lead and sponsored by AMS, provide

a good example of how the meaning of "public space" has

changed in Poland during the last two decades.

|

| Twozywo,

When Is a War finally Going to Happen?, Campaign

2000, Courtesy AMS and Twozywo. |

|

Under Communist rule

the term "public space" did not exist. Being part of the

official ideological realm, public buildings, company headquarters,

streets, and squares remained a medium of the regime’s propaganda

for over thirty years. Controlled by security officials and the

Polish United Workers Party the outdoor premises, known currently

as "public space," were not accessible for artists with

the exception of those who served the official political system.

Of course, the censors were sometimes not intelligent enough to

do their job or had some sense of humor. It is hard to imagine that

at a time when every image and word shown to the public required

permission of censors the pathetic slogan, "Socialism is Our

Target," was affixed for many months to the Hunters’

Union building in Warsaw, provoking much laughter among passersby.

There is also a famous photograph of the Moskwa (Moscow) Movie Theater

in Warsaw taken during martial law. It pictures a huge banner advertising

Francis Ford Coppola’s movie Apocalypse Now! on the

wall with police military forces marching in front of it outside

the building. This image became one of the most memorable of those

difficult times.

As a student of humanities

during the martial law period, I observed for some time how a wall

might become the object of an ideological battle. Taking a tram

to the university campus, I would go through a narrow passage, facing

one of the adjoining walls. "Down with Communism!" stated

the graffiti one day. Overnight some policeman covered the sentence

with fresh paint: "Down with Solidarity!" This dialogue

continued with different contradictory sentences for the next few

mornings. Finally the representative of one of the groups put on

the wall: "Down with violation of the law!" This survived

for quite a long time as it made everyone happy because the meaning

of "violation of the law" was entirely different on

both sides.

After the political

transformation of 1989, when Poland officially became a parliamentary

democracy again(1) the entire situation changed.

Since the advent of outdoor market commodity advertisement, Poland

has been shaken by several battles about freedom of market and its

ethical approach. The content of an ad as well as the right to advertise

certain products seems to create as hopeless a discursive impasse

as pro-life, pro-choice, and other ideological dilemmas. It is mutually

insoluble.

AMS started its Galeria

Zewnetrzna project in 1998(2). The company sponsors

art projects by leading and emerging Polish artists in regular campaigns

that present an edition of 400 posters in major cities. Another

project supports younger artists and groups to create a single piece

on one temporarily donated billboard panel(3).

An art historian, Lech Olszewski, is the company’s marketing

director, and he runs the project with sociologist Marek Krajewski.

They also support and collect some other phenomena of temporary

interventions in public space, such as stencils and so-called "vlepki"

(stickers illegally applied onto legally existing objects). Galeria

Zewnetrzna’s program is innovative in a country with a strengthening

advertisement market. It represents a buffer zone between the cynicism

of contemporary commercial marketing and the ambitions of a Polish

artworld that is having difficulties clearly communicating with

its audiences(4). Using double-edged sword strategies

to protect both the company income and its satisfaction with doing

something creative, AMS has to make compromises in order to continue

the project. In its promotional materials the gallery directors

said: "The gallery is going to promote aesthetic alternatives

to boredom and to the instrumental kitsch of the Polish contemporary

city’s ionosphere.... In future editions of our venture we

would like to present... antimoralistic and nonpropagandistic works,

but at the same time involving both as content and form."

|

| Pawel

Susid, Zle zycia koncza sie smiercia/ Bad Lives End

with Death, 1998 (first campaign, edition of 400) |

|

The AMS Outdoor Gallery

got off to an ambitious start in its first year with a campaign

entitled When Another Becomes the Other (this also could

be translated as When the Stranger Becomes the Other).

Pawel Susid’s Bad Lives End with Death, Anna Jaros’

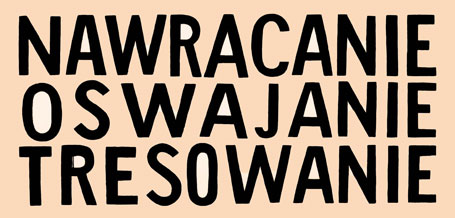

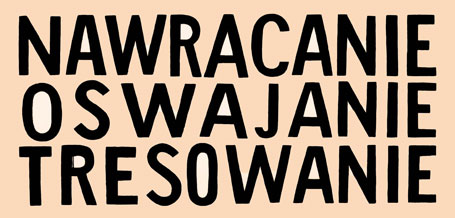

We Are Horrible, or Jadwiga Sawicka’s Converting.

Domesticating. Taming discussed some social issues, such as

the acceptance of difference or the pressure of cultural paradigms.

|

| Jadwiga

Sawicka, Converting. Domesticating. Taming.

1998 (billboard edition of 400) |

|

Enthusiastic press coverage

helped to promote the project. But these first projects were not

that disturbing as images, and their message was not very direct.

Their meaning depended on the context of some other accompanying

commercial ads. The situation changed in the summer of 1999.

|

| Katarzyna

Kozyra, Blood Ties, 1999 (billboard edition

of 400 copies) |

|

Katarzyna Kozyra, a younger

artist and the winner of an honorable mention at the 48th Venice

Biennale, was chased by the media and persecuted by right-wing politicians.

She had become the informal winner of the national contest in controversy

(if such a thing existed!). Thus no one was astonished when a billboard

version of her Blood Ties produced in 1999 for the fifth

edition of project caused greater turmoil compared to the previous

ones. Blood Ties was made originally in 1995 as a four-piece

photo work(5). Two of the photos show Kozyra nude

and another two show her naked sister with a handicapped leg. Both

young women lay down on a background of a red symbol--a cross or

crescent--centered on white. Another element of the images are compositions

of vegetables--cabbages or cauliflowers. All of the components are

selected by usage of the principles of similarity versus difference.

So siblings of similar age and appearance are differentiated by

the use of images of disability and two great religious systems

are depicted in conflict regardless of the common roots of their

belief. And, of course, there is a reference to two famous charity

organizations, which serve on war fronts around the world. For the

billboard edition Kozyra selected two of the four images. She stated

officially that she relates her work to the situation of victimized

women during the war in the former Yugoslavia.

The work infuriated some

right-wing politicians. One statesman from Gdansk even detected

Satanism, since one of the young women is photographed upside down

on the cross. Joanna Fabisiak from Solidarity Voting Action (AWS),

who collected 800 Warsaw inhabitants’ signatures under a petition

against the poster, explains: "This is not prudery or bigotry,

but only a protest against liberalization of social norms."

Undoubtedly, similarly to many other debates about the morality

of art, this conflict is another ideological battle between liberalism

and conservatism. Some members of the Polish Parliament accused

the artist of offending the feelings of believers and tried to look

for allies in some Islamic countries’ embassies in Warsaw

but those diplomats declared politely that actually they enjoyed

the pictures. Although those politicians did not succeed in creating

an international scandal, the situation became too much for Polish

authorities and the budget of Kozyra’s presentation in Poland

National Pavilion at the Venice Biennale was radically cut. The

posters were partly covered with paper, due to decision of the AMS

management. Some cities asked the company to refrain from exhibiting

the piece on their streets and their statement was accepted. The

spokesman for the Polish Episcopate, Adam Schultz, stated that he

can identify with the message of Blood Ties but he does

not accept its form.

|

| Marek

Sobczyk, “What?: Repetition”, 2001

(edition of 400)

Courtesy AMS and the Artist |

|

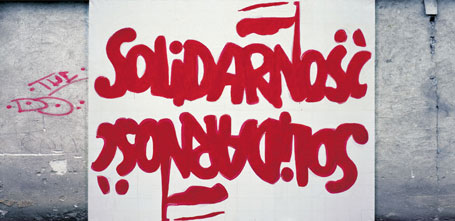

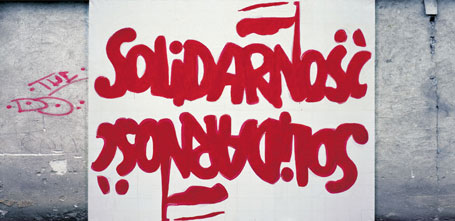

The fourteenth edition

of the Outdoor Gallery Project in the summer of 2001 was a poster

version of Marek Sobczyk’s What? Repetition (Solidarity).

Just a few days before the 21st anniversary of the Solidarity movement,

Sobczyk reminded the Polish nation of one of the most important

cultural icons of the 80s, the famous red logotype of Solidarity

that became an international trademark of resistance and victory

of freedom. Sobczyk repeated the symbol upside down in a mirrored

reflection. As the curators of Galeria Zewnetrzna noted the artist

asks about the actuality of the value system that Polish society

used to associate with this mark. Sobczyk’s project coincides

with and emerges from the political situation of an electoral campaign,

when the government established by Solidarity officials lost the

trust and backing of the voters.

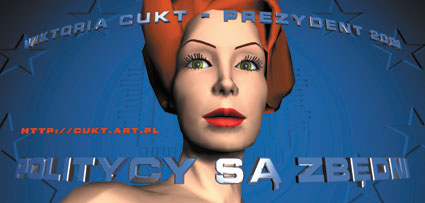

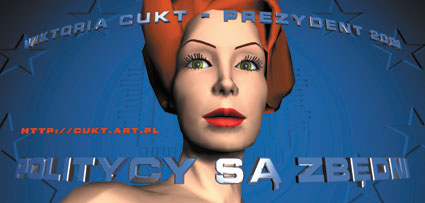

In 2000, the artists

from the collective project named the Technical Culture Central

Office (CUKT) had run a fake election campaign, scheduled for the

entire year of the real presidential election in Poland.

|

| Technical

Culture Central Office [CUKT], Wiktoria CUKT

Campaign, 2000 (edition of 400) Courtesy AMS and the

Artists |

|

The artists created a

candidate for the President of the Republic of Poland, who was not

only a young attractive woman, but also a fully virtual, computer-generated

being. The campaign of this long-legged beauty started on the internet.

The idea was to promote the internet as the tool and institution

of a democratic society. But, of course, the artists played with

the illusion of democracy. The candidate was perfect for everyone,

as she shared every opinion sent to her by e-mail. Her statements

were completely contradictory, so as to please every possible voter.

This internet project was followed by several election meetings

and finally a billboard campaign with AMS, released exactly at the

moment when "real" candidates started to present their

own ones. This campaign really appealed to the Polish sense of humor,

especially when the billboard of Victoria CUKT was shown, for instance,

next to the billboard of President Krzaklewski from the Solidarity

Union. Mr. President, whose campaign was based apparently on his

attractive look(6), had no chance against red-haired

Victoria. Regardless, she lost, but so did he(7).

|

| Two

candidates: Marian Krzaklewski and Wiktoria Cukt, 2000

(picture taken in Gdansk, corner of Walowa and Lagiewniki

Streets), Fot. Grzegorz Klaman |

|

While some of the Galeria

Zewnetrzna’s critics complain about most of the art billboards,

indicating their lack of communication and clarity, more direct

and provocative projects are criticized just because they are clear

and communicative. AMS seems to be in a radically blocked situation,

because most of the criticism comes from local politicians, and

the economic situation of the company depends on good relationships

with local governments. Online magazine Media i Marketing Polska

noticed over two years ago that the situation may affect the AMS’s

development and warned that the company may earn, since provoking

Behaviors hard to accept(8), a reputation

as a controversial company.

During the last ten years

we have observed an increasing number of billboards in the countryside,

caused by the lack of legal regulations, especially in the earlier

period of establishing outdoor advertisement companies. Seen practically

everywhere, in the most unexpected places, the billboard advertisements

violently assault the eyes of the viewer and became one of the most

successful mass-communication media. The only significant difference

between art on billboards and art presented indoors is that it is

shown to everyone unintentionally passing by. AMS Outdoor Gallery

has the biggest audience among all of Polish art projects. It is

also, more than any other art project, influenced by undercurrents

of public opinion. As opposed to museums, it is not taking the risk

of a cut-off of public funding but, rather, the loss of market income.

Theoretically there is more freedom for a private, self-financed

project, but when it takes place in a public domain, the situation

is especially complicated. Considering these limitations, Galeria

Zewnetrzna had to apologize several times for misunderstandings,

miscommunications, and wrongly interpreted intentions. As Marek

Krajewski stressed in his press release, the idea of his outdoor

gallery comes from the lack of educated gallery-goers and a lack

of professional art criticism in Poland. By dragging contemporary

art into the public space Galeria Zewnetrzna influences the reception

of art, which becomes a part of the public discourse.

Regardless of most of

the debate’s rhetoric, no less populist than most of the political

battles in the country in general, the discussion these art billboards

provoked made citizens more aware of their rights and of the collective

ownership of public spaces and the importance of visual culture.

Despite the troubles involved with exhibiting contemporary art in

public institutions, art on billboards has become an important element

in the negotiation of a structure for the transformation of society.

Is it a step on the path to understanding public art? Or is the

negation and lack of understanding necessary for public art to exist?

(1) Poland is the oldest democracy

in Europe; the constitution of 3rd May is dated 1791 .

(2) The Outdoor Gallery also publishes free postcards

and maintains its own WebPages. Some other artists who took part

in their activities are: Jadwiga Sawicka, Pawel Susid, Monika Zielinska,

Rafal Bujnowski nad Sanislaw Drozdz. For more information search

www.ams.com.pl ;

(3) ICf. Galeria Otwarta in Krakow, its archive

and the locations map at www.galeria24h.virtual.pl .

(4) More about reception of contemporary art issues

in Poland in: Aneta Szylak, “New Art for New Reality. Some

remarks on Contemporary Art. in Poland,” Art Journal,

Spring 2000.

(5) One poster of the billboard edition was presented

in NYC at Exit Art in Fall 2000 in the exhibition The Body of

the East curated by Zdenka Badovinac from Lubljana.

(6) And a slogan “Krzak Tak” what means

“Krzak (his nickname) yes”, qualified by some political

marketing advisors as “the silliest election motto ever”;

(7) For more information search http://www.cukt.art.pl

;

(8) JP, Manipulacja przeslaniem, Media i Marketing

Polska, 3.06.1999.