M/E/A/N/I/N/G 25th Anniversary Edition

Introduction

We started M/E/A/N/I/N/G in 1986 as an intervention into a particularly charged political and discursive moment when the accelerating hype of the 1980s art market marched in curious tandem with institutional and commodity critiques often announced in obdurate and obscure theory language. If “intervention” was one buzz word of the day — defining a limited political act distinct from the large utopian movements for social change of the 1960s and 1970s — “irony” was another, contributing to a moral equivalency and destabilizing humanistic concepts including that of meaning itself.

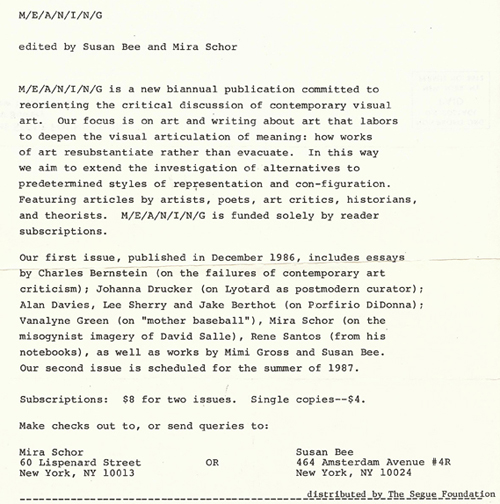

From the subscription flyer for issue No. 1:

M/E/A/N/I/N/G has been a collaboration between two artists, both painters with expanded interests in writing and politics, and an extended community of artists, art critics, historians, theorists, and poets, whom we sought to engage in discourse and to give a voice to. Over the years we created a community of M/E/A/N/I/N/G. It once existed in a red plastic index card file box, later in a primitive mailing list program, then an e-mail list, and now is also reconstituted in our online friendships.

The first issue of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A Journal of Contemporary Art Issues, was published in December 1986. We published 20 issues biannually over ten years. In 2000, M/E/A/N/I/N/G: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings, Theory, and Criticism was published by Duke University Press. In 2002 we began to publish M/E/A/N/I/N/G Online and have published four previous online issues. The M/E/A/N/I/N/G archive from 1986 to 2002 is in the collection of the Beinecke Library at Yale University.

Our 25th anniversary comes at an unusual moment following upon a series of traumatic political events and a decade of war. It is a moment of global economic crisis, failure of capitalism and of progressive political movements, a moment of political impasse, and of generational shift. Methods of communication have changed since we began our project 25 years ago and concepts of privacy and individuality seem to be in a process of radical transformation.

We began planning this issue in the way we had planned other forums in the past: we discussed and tried to formulate our specific personal concerns and our sense of general contemporary concerns into questions and themes that we would invite a spectrum of artists to respond to. Our mutual and separate lines of thought and feeling merged into two themes:

Theme 1

How do public traumas like 9/11, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the rise in income inequality in the U.S., and the current recession affect, or frame, the production of your art works and art criticism? What is the role of individual style or idiosyncrasy in these times and circumstances? What is the role of the art market/fashion/art history versus such public or individual/idiosyncratic motivations and frames?

Theme 2

How do artistic intuition, creativity, community, production, and distribution function for you in the age of digital corporate conglomerates and the web 2.0? What is the nature of privacy for the artist or critic working in the age of social networking and global spectacle?

We were surprised and delighted by the enthusiastic response to our initial invitation sent out in mid-August to a wide spectrum of artists, critics, historians, theorists, and poets, some who had written for our journal before and many new artists and writers whose work we have encountered in recent years.

Many people, perceiving a fluid relation between the questions of trauma and of privacy that perhaps was inherent to our own thinking all along, addressed both of our suggested themes in their responses. Therefore we have organized the issue alphabetically rather by theme.

We are honored to publish the responses we have received. People wrote what they really thought and felt, each very individually, many clearly inspired and energized by the Occupy Wall Street movement, which began September 17th in Lower Manhattan and has rapidly sent a wave of optimism around the world.

Susan Bee and Mira Schor

New York City, November 2011

Suzanne Anker

Cold Cases and Cultural Catharsis

Making art in the 21st century is a fractured set of “isms” that range from marketing mayhem, to syndicated multicultural modernism, to art as a knowledge production system. Each of these subsets carry prescribed methods of investigation, reception and consensus. Specialized subcultural audiences complete with glamour-driven productions take their place on the consumption line, while aesthetic tourism generates art groupies who globetrot the international art fairs, biennials, and exhibitions.

On one hand these strategies are quite transparent and materialistic and at other times they neutralize art’s underlying capability of exposing political platforms or inventing experimental forms and formats. Even in faux-form, cultural products join the ranks of smoke-screening devices if they masquerade repressive human rights, gender inequalities and Enlightenment envy. Expedited by Internet access and digital diving, the rate at which staying in-tune creates conditions for multi-tasking and other diversionary tactics. Such approaches are taken at face value and reflect media sources in which very little real dialogue can take place, sometimes out of fear or even shame. At a time when discourse is indirect or even hidden, objects and images continue to be trophies of power positions.

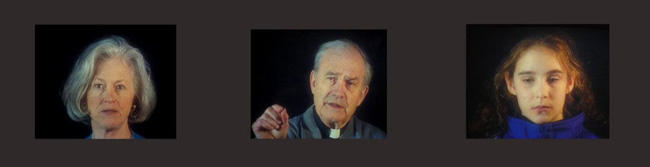

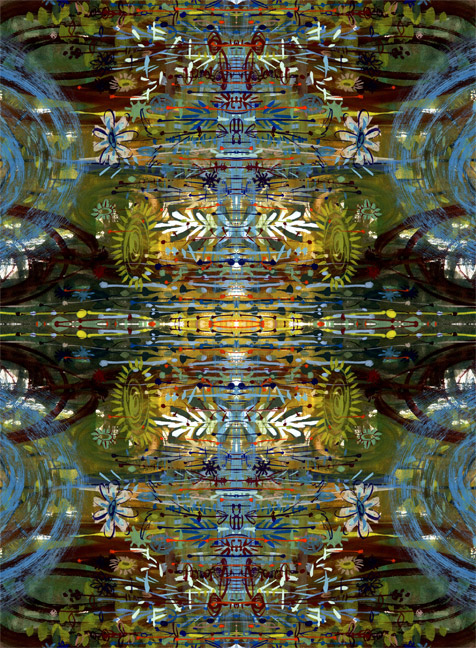

Suzanne Anker, Corpo Duplice (Self-Reflection), 2008, digital print on watercolor paper, 24" x 36".

This moment in time is one of mania in which distraction becomes a genre in itself. Making art under these conditions is wrought with dystopian dreams, putting into jeopardy historicity, authenticity, and subjectivity. Reality TV, extreme couponing, bonus points, and cash back lure the everyday dope into circadian reveries. In this zombie-like state, feeling is numbed, and actions are rote. At a time when self-promotion and celebrity status continue to further erode more introspective ideals, separating out the valor from the perverse is equally difficult. Adjusting to changing paradigms of turbo-capitalism the poetica episteme is subordinated to market shares. . . .

Simultaneously, my working methods rely more and more on research. My art practice has migrated towards methodologies incorporating other disciplines, looking at the ways in which archives and collections, materials and processes are comprised of back stories.

These narratives, not immediately obvious to the viewer are gleaned for historical content, symbol sets, and embedded metaphor. More than a singular or repetitive studio practice, my work is engaged with artifacts in the world and how they generate meaning. At this time of media overload, what image-schemas can be constructed which map subjective experience? From jihad to iPad, are we all angry birds now?

Suzanne Anker is a visual artist and theorist working at the intersection of art and the biological sciences. She works in mediums ranging from digital sculpture and installation to large-scale photography, and plants grown under LED lights. Her work has been shown in museums including the Walker Art Center, the Smithsonian Institute, the Phillips Collection, the Getty Museum, and the Mediznhistoriches Museum der Charite in Berlin. She is chair of the Fine Arts Department at the School of Visual Arts in NYC.

Eleanor Antin

Then and Now

This fall, here in Southern California, we’ve been caught up in the Getty-backed extravaganza we call “PST” (“Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980”). For about 6 months, something like 60 museums, alternate venues, and galleries are each doing theme-related exhibitions to rediscover the rich history and inventiveness of the post-war period in the most southwestern part of the country. I mean you can’t get further from New York without drowning in the Pacific Ocean. Many of us are in several exhibitions because of the variety of our interests and practices. The exhibition at MOCA in L.A., “Under the Big Black Sun,” which is showing a 1976 work of mine, The Nurse and the Hijackers, gave me an opportunity to consider this political work of 35 years ago in the light of today’s contemporary politics. It has amazed me to see how similar we were then to where we are now.

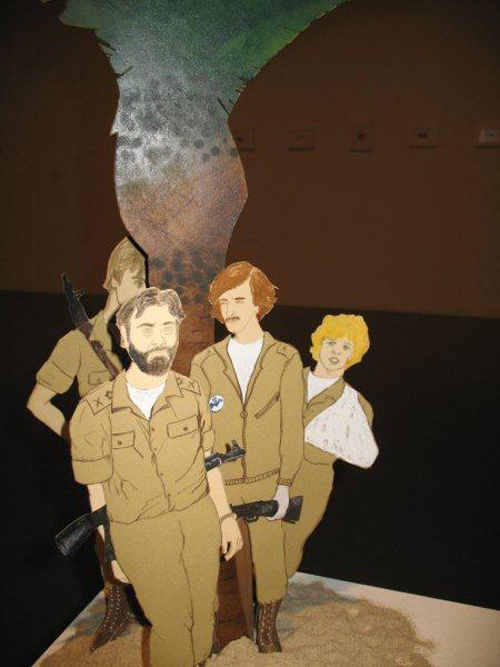

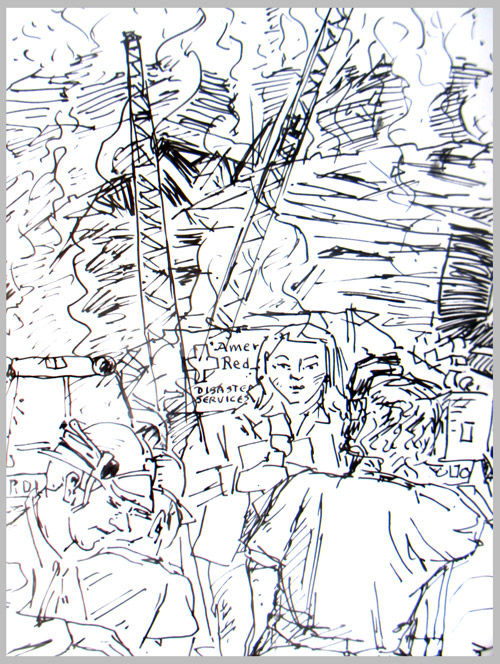

Eleanor Antin, Desert set from The Nurse and the Hijackers, 1976, dimensions variable.

The Nurse and the Hijackers employs the structure of a still popular movie genre, the disaster movie, as an armature to consider how in this age of alienated government and institutions, people find themselves more and more removed from the sources of power, even over their own lives, especially over their own lives. I began to see how hijacking was one of the ways that the powerless could reach the power centers quickly and cheaply through a media in love with disasters and death. Actually my hijackers are eco-terrorists, who fly their hijacked plane to the Middle East. They’re hoping to convince the OPEC nations not to sell their oil to the imperialist West in order to avert the human and ecological disaster toward which they believe an amoral technology has been leading the world. They fail, of course. In fact, they’re ecologically smart but politically stupid, since OPEC is short for Oil Producing and Exporting Country.

There’s something of a paradox in this work. The hijackers’ arguments about oil and the disintegrating environment makes even more sense today and they’re certainly not out to kill anyone. They’re aiming to cure the world of its petroleum disease. Only the Middle Eastern governments that they’re trying to persuade to cure this oil disease are the people who benefit from it. But today, with the new terrorism, the paradox is lost. Today, it’s impossible to make a hijacker look benevolent or sympathetic. Thinking about people who aren’t out to argue about ideas of how to save the world but are out to destroy themselves and everybody else in their vicinity, is a whole other ball game. This is a dark irony that did not exist back in 1976.

Little nurse Eleanor happens to be aboard this plane along with a cast of stock characters . . . like an ex-jock turned sportscaster yearning to be an anchorman, an alcoholic movie star, a middle-aged couple on their way to a wedding in Israel, you name it. Then there are the idealistic hijackers and the Algerian bankers, Libyan colonel and several sheiks whom they fail to persuade. These stock characters form the material out of which the narrative is created. You might call it an Arte Povera work of sorts, since in those days I certainly couldn’t afford actors, and my means were those that were freely available to little girls everywhere . . . paper dolls and narrative invention.

Eleanor Antin, The Tourists, 2007, chromogenic print, 61" x 77 7/8".

I’ve been telling stories and playing with depraved genres to represent the political and cultural disasters of our contemporary world since I began making art back in the 1960s. And I’ve continued right up to the present with my large photographs of live actors in ancient Roman settings and dress enacting allegories of the fall of empires that bear a strong resemblance to our own disintegrating American empire.

Eleanor Antin works in a variety of media, including photography, video, film, performance, installation, drawing, and writing. An emeritus professor at UCSD, she was a featured artist on Art 21 on PBS and has had many solo exhibitions, including at the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum, and a retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Antin has just completed a memoir, Conversations with Stalin. Her other books include Being Antinova (Astro Artz, 1983) and Eleanora Antinova Plays (Sun & Moon, 1994).

Susan Bee

I’ve found, in making my art, solace from both private grief and public trauma. So our first question for this M/E/A/N/I/N/G forum has great resonance for me. Still, I find my motivation for making a painting or artist’s book is not necessarily apparent to a viewer. I would say that my artworks are a kind of Vergangenheitsbewältigung (coming to terms with the past). This term has been used by postwar Germans to describe their attempt to confront their recent history, yet, perhaps oddly, I find it suits my search to find an emotional and intellectual balance through art.

My parents came out of the cauldron of Berlin and Nazi Germany and Palestine to find their way as Jewish artists in America. As the child of immigrants, I inherited their fears and insecurities as well their pride and optimism in their new country. The sudden death of my father Sigmund Laufer in 2007 was followed by the unimaginable suicide of my 23-year-old daughter Emma Bee Bernstein in 2008. I found that I had to regain my footing in the world and that through the imaginary narrative of painting I was able to embody my pain and transform it. But transform it into what? Perhaps I can just say an altered world.

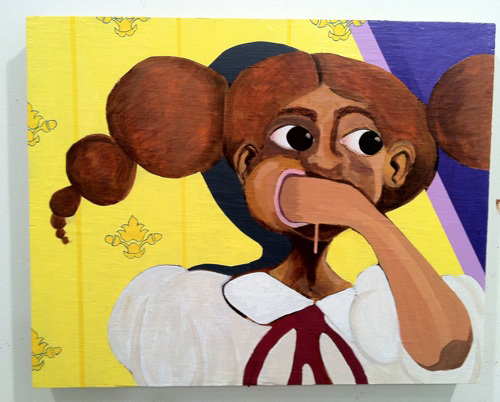

Susan Bee, Woman Tormented by Demons, 2009, oil on linen, 18" x 14". Collection: Regis Bonvicino.

As the late poet Akilah Oliver wrote in relation to the tragic death of her 20-year-old son: “In approaching the subject, the death of the beloved, I enter into an investigation of the ecstatic in the dual sites of rapture and rupture. For me, an absolute rupture occurred at the time of my son’s death, so that the world broke open, in a sense, and I decided to follow the opening to wherever it led, rather than try to patch it and close it. . . . I think . . . for me, to write is a kind of difficult dance with rapture; it is a way to beckon the day as a beloved, a way to talk to the dead, a way to collapse the known world into the impossible.”

Susan Bee, Drive By, 2009, oil on linen, 14" x 18". Collection: Rachel Levitsky.

Jews talk about tikkun olam, repairing the world. I have found overwhelming support in the past few years from the community of artists, poets, and friends that has surrounded my family. I am very grateful for having this continuing presence in my life.

Unfortunately, repairing the world is extremely difficult, as we see daily in the global strife of wars, recessions, and endless environmental damage. Greed, enmity, and the enormity of our current problems can seem to engulf the vision of an individual artist practicing a rather antique art form, such as oil painting, in a small studio. The studio can serve as an escape hatch or a meditation chamber or an experimental lab, where color, composition, dreams, and conscious and unconscious intentions meet. Often, I find that this space is a tiny resting space and holding action against the juggernaut of the commercial art world and the disturbances of contemporary life. I was downtown on September 11th, 2001, within a mile of the World Trade Center, on my way to my studio on Canal Street, when the buildings came down. Within days I returned to my studio to work. I found comfort in that as a healing process and it provided consolation and a way of continuing on with my projects.

Susan Bee, Go Forth, 2011, oil on linen, 20" x 16".

I am heartened by the new activism at Occupy Wall Street that is now taking place within blocks of Ground Zero. I do still believe in the importance of the communities we can create as activist artists, whether in cooperative galleries like A.I.R., publishing ventures like M/E/A/N/I/N/G, or in the workplace, for instance in forming unions for adjunct professors, so that we have the job security and benefits that we deserve.

As to the second question that we framed for this 25th anniversary issue, I greatly appreciate the sharing and instantaneous communication that the web provides. When we started M/E/A/N/I/N/G in 1985, there was no web and no personal computers. Our invitations were sent in the mail and our communications were made in person and on the telephone. News traveled more slowly and time seemed to pass in a different manner. I like that but now I also like the sense of community that social networking sites and the web and e-mail provide. I do think my privacy has probably been eroded, but I still feel my inner life is mine alone to share or not as I wish. It is strange to leave the world of our magazine with its printed issues, for this brave new space of instant communication. As Mira has noted elsewhere, we used to run into people on the street, and waited to hear back from people who had received the issue in the mail. We dragged each issue in heavy bags to the post office. Our publishing experience was as different in pace as the horse and buggy era is from the experience of car and airplane travel. Still we feel privileged to be able to continue our project.

I hope that this new sense of community will light sparks for a new vision to fan out into this troubled and globalized 21st century.

Susan Bee is an artist, editor, writer, and teacher living in New York City. She has had six solo shows at A.I.R. Gallery in New York City and has published many artist’s books, including collaborations with Susan Howe, Johanna Drucker, Charles Bernstein, Regis Bonvicino, and Jerome Rothenberg. She is currently teaching at the School of Visual Arts, NY, and the University of Pennsylvania. Bee is represented by Accola Griefen Gallery and A.I.R. Gallery in New York.

Bill Berkson

Variations on a Theme

There is no love interest in these modern wars.

— Gertrude Stein, 1943

It’s said that the more examples you show of suffering the smaller the impact. One sad case is tops. The casualty list looks blank unless you’re searching for a name. In Gertrude Stein’s Brewsie and Willie, Willie says, If you fight a war good enough everybody ought to get killed. A little later Brewsie says, Oh dear, I guess you boys better go away, I might just begin to cry and I better be alone. I am a G.I. and perhaps we better all cry, it might do us good crying sometimes does.

Ted Berrigan said he heard a gunshot in the night in Korea, outside the base. Kenneth Koch lost his glasses in a foxhole somewhere in the Pacific, bullets whizzing. “Killer Kenneth.” Frank O’Hara stood on the deck of the USS Nicholas, spotting enemy planes, horrified that he might be the cause of the next great Japanese composer’s going down in flames. Robert Creeley drove an ambulance through Burma. What happens when poets go to war, as they will, but nowadays rarely? (Some mystery in that.) “War is shit,” wrote Ted in one of his Vietnam-vintage poems. Some of us are just perpetual observers, like Tolstoy’s Pierre threading through the dead and wounded at Borodino.

For those who were in it, varying degrees of persistent horror seem inexorable: “war torn,” “battle fatigue,” “shell shock,” and the now clinically approved “PTSD.” (A bellyful of scare quotes there.) O’Hara went on to Harvard and wrote an attempted exorcism, “Lament and Chastisement,” its finale choir screeching like out of a bad dream.

Poets and painters have a high command. Few of my friends have ever been in any army, nor have I. Fat chance of that. Our love interests lie elsewhere. When in the midst of the Cold War I told my father I wouldn’t join no matter what, he called me “a pigeon for the Reds.” Nevertheless, we have rage, aggression, defense mechanisms, a taste for revenge, inordinate cruelty, appalling as all those may be, as well as resentment, pride and shame. I remember a poet friend in 1967 or so telling me he was going to join the army — because, he said, “I need to kill someone.”

Is that a real soldier, fuck or fight? The professional — commander or hoplite — is one thing. My uncle Kent the career cavalryman, rode horses in WWI and tanks in WWII. In the latter, on George Patton’s staff in North Africa, Sicily and onward — a disreputable association that left him shunted at war’s end, his last years as colonel-commandant of the dress post Governor’s Island. His daughter, my ninety-three-year-old cousin, says he was generally “naughty.” Lean, elegant, persuasive, sporting a neatly trimmed mustache, a lightning-bolt Armored-Division patch on one sleeve of his uniform jacket, he was the closest I ever got to a military life.

Fuck or fight? Walter Reed is closing, the troops may well be pulling out, but the drones keep flying. John Keegan’s A History of Warfare reads like a biosketch of collateral humankind. But strangely omitted is the sense of how soldiering fits with the everyday economy. At the Selective Service Induction Center in Lower Manhattan, 1960, I overheard people my age eager to get in, get the job. “Hope he doesn’t spot my trick knee.” Growing up absurd, with no higher prospect. I on the other hand wanted out; ambitious to avoid, certified 4F by a picture-perfect Viennese émigré camp psychiatrist, psyched, watching my hands shake when he told me to hold them out. The desk sergeant handed me a lunch ticket for the mess hall; an hour later I sat drinking vodka in Frank O’Hara’s parlor, wondering if I had missed out on some crucial experience.

Note: The present text consists of excerpts and variants on “Soldier, Rest,” an introduction to Anne Waldman and Noah Saterstrom’s Soldatesque / Soldiering: With Dreams of Wartime (BlazeVox Books, 2011).

Bill Berkson’s most recent books include Portrait and Dream: New & Selected Poems; a collection of art writings, For the Ordinary Artist; Not an Exit, with drawings by Léonie Guyer; and Repeat After Me, with watercolors by John Zurier. He is Professor Emeritus at the San Francisco Art Institute, a contributing editor (poetry) for artcritical.com, and a corresponding editor for Art in America.

Charles Bernstein

The Pataque(e)rical Wager

In the sixties, we used to say, heighten the contradictions. And then, when the contradictions were so excruciatingly high that you’d think the political center was some kind homebrew of meth and glue, things just seemed to get worse. And that longed-for breakthrough in collective consciousness not only didn’t happen but seemed, each day, that much further away. I know, Gramsci, pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will, I got that tattooed to my cerebellum, but some days the will’s just not there any more. (You know you’re old when the promises of youth become clues to a map of a lost world 20,000 leagues under the Edward I. Koch “Feelin’ Groovy” 59th Street Bridge.) I always thought those who described George W. Bush as incompetent missed how successful he was in creating irreparable environmental damage and that how well he succeeded with his agenda, including massive redistribution of wealth (crude as this measure is, the flow of money from the many to the few is a fairly accurate guide to Republican Party policies). So, perhaps more than ever before, I began to internalize the public events of the days. I felt I was being poisoned by them.

The Sixties, with Apologies

I remember the future, how it was

So much like the past, those days

Rowing on the lake for the sake of

Rowing itself, never looking out, never

Any ducks lined up, only the fragrance

Of fragrance, the similes on a smile

Touched by an angle. As if our fund

For hedges was any more effective than

Duping, duking, doping, throwing

Cold water on sizzling runes. Jesus

Would have dug it, before he got hung

Up in all that superstructure. Even

The water withers in the mouth, like

Hope evaporating in the words of the

Town criers and motion sensors. Gale

Winds diminish in the mind since

Whatever is apparent and clear in

My brain is so much Yukon flu.

The utter white spaces of deception.

It’s ok, but I did that 20 years ago.

Millions of miles beyond care, sobered

Up on 12-year-old bourbon & lobster

Rigamarole. The blood on George Bush’s

Hands keeps coming out in my stool.

Night is never dark enough because

Everything I see frightens me.

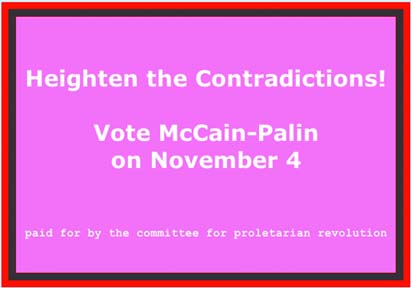

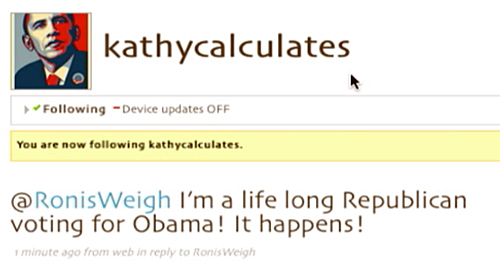

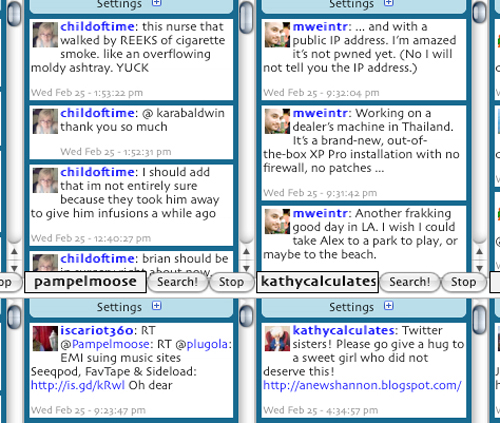

When the 2008 election came around, I wanted to see a public art that pushed back against the “fair and balanced” double-binds of the mediocracy (antiwar sentiment on Iraq was the equivalent of pro-war sentiment, the Bush lies were as valid as the questioning of the lies). How is that those of us in the streets demonstrating against the invasion of Iraq in 2003 knew the claims to WMDs were unverified while the massed media did not? Yes the answer is obvious: I am speaking here to my emotional reaction to, let’s call it, the ideological terrorism of constant mendacity in the massed media. Symptoms: Unproductive anger and frustration, mixed in with a range of not apparently related frustrations and disappointment both personal and with developments in poetry and art. The left and liberal mainstream publications are so addicted to self-restraint that they don’t allow much in the way of unruly political art; in any case, let’s not let tainted/confused emotions get into it, surely that will undermine the legitimacy of our position which is grounded in rationality alone. I was seeing probity but I was wanting satire, sarcasm, irreverence, outrage, mocking. There is no wide-circulation public forum that would publish my idiosyncratic political placards. But I had my own web site and could — quicker than you can say Tom Paine three times backward — while walking over shards of discarded Dells (I love the smell of burning operating systems at midnight) — publish my own forays into common sense (or from the point of the mediocracy: eccentric musings, what I now call my pataque(e)rical wagers). When Ken Jacobs recently looked at a bunch of these works, he wrote me “I can envision the sleepless nights that produced these.” And he added, “Isn’t there a saying, ‘irony closes out of town in two days’?” If there is, I sure never heard it. But I know what he means. This is my new quest: unpopular public art, with always the same joke that, by necessity, could never be funny. And that makes a point with which almost everyone in the audience already agrees (sort of). My private recurring nightmares were coming from what I read in the newspaper each morning. Here are a few:

Fall 2008

Fall 2008

Fall 2008

January 23, 2010

July 21, 2010

P. S. What a difference a few months make. I wrote my essay for M/E/A/N/I/N/G in August 2011. By mid-October, with the Occupy Wall Street movement in full swing, the anger bordering on despair many of us have been feeling had found what looks to be an almost adequate public form of expression (I prefer adequate to perfect). Collective outrage has been growing for years and will continue to find its voices. The poetics of OWS are appealing partly because they are averse to the kind of policy declarations that the mediocracy craves. Similar to the criticism of Barack Obama, in campaign mode, being too poetic (and who doesn’t long for him to return to that?), the very ambiguity of the OWS protest opens it up to multiple, not doubt contradictory, affiliations. Slogans and aphorisms play a strong part in this, as with other populist protests, which use tactical framing to reorient attention. At OWS, we hear “This is what democracy looks like,” “Banks got bailed out / we got sold out,” and of the eponymous “We are the 99%.” The spirit of the marches, calm and friendly (as of this writing), does have something of the spirit of the late 1960s, but more the be-ins in Central Park than the more confrontive Chicago ’68 demonstrations or the student occupations of those years (and so far no police plants or weathermen to promote trashing store windows after hours, nor police forces going on rampages, at least to the extent we experienced it in Chicago). When OWS protestors say the whole world is watching, they mean that in a way that was not imaginable in Chicago in 1968 (where that chant was popularized). Those without signs have cameras: images are constantly being uploaded to the web, which surely has a welcome chilling effect on police response. But OWS wants something else: not the whole world watching but the whole world participating.

Charles Bernstein is the author of Attack of the Difficult Poems: Essays and Inventions and All the Whiskey in Heaven: Selected Poems. He teaches at the University of Pennsylvania, where he chairs the Program for Stand Up Poetry and Avant-Garde Comedy and heads the search committee for Chief Rabbi, First Church, Poetic License.

Nayland Blake

Let’s talk about the sense of dislocation that accompanies so much online experience: the rootlessness, the sense that there is always something else over there beyond the horizon. Ideas and images arrive on my screen with the barest effort on my part. Sites like tumblr immerse me in a flow of pictures that tug at my attention for a moment or two before being quickly supplanted by still more pictures. If I really like something I may right click and save the image to peruse “later,” although that later only rarely arrives. I use tumblr as a source for things I’d like to think about, and I can feel the sad way that this “future thinking” is taking the place of me actually thinking about things. When I meet with students for the first time I often ask them what do you “reread” or in the case of movies rewatch. Increasingly people tell me they don’t do that. When it comes to information online, I don’t do it. Images and words dissolve in my mind like a communion wafer on the palate of a skeptic: here for a second as a reminder and then gone. In this sense online culture turns treasure into something to be waded through, to get done with. The chores of communication, making us all into content pushers.

I was initially asked to contemplate the idea of global spectacle. I don’t think we live in such an age. We no longer have the sustained attention that allows for spectacle to work as a unifying force. Instead we live in a time of flash attention mobs, where memes “go viral” in the twinkling of an eye and the dance of a finger on a button means that thousands of people have supposedly responded to the thing you made. This is the tyranny of the Nielsen rating.

I’ve come to believe that art works are deeply contextual utterances, that much of their conception occurs when the artist is thinking about a specific act for a specific place in concert with a specific group of people. Once the work exists, it may or may not be taken up by all sorts of people in unanticipated ways, but the problem for the maker is not one of anticipating all possible responses, but rather how to understand the meanings that are fighting to the surface in that particular piece of contextual thinking that the artwork embodies. That’s another way of saying I make art to find out what I am thinking about my place in the world at any particular time and as such, knowing that 50 or 5000 people “liked” it is a metric that is useless the next time I try to make something.

The logic that governs online value is the logic of mid-century advertising, where the assumption is that the more eyeballs that see an ad, the more effective it is likely to be. Why else have friend counters in Facebook, numbers of followers on twitter? The earliest personal web pages had visitor counters, as you may remember. The information about the number of people who have seen things is useful to advertisers, but useless for artists, because the quality of those encounters escapes measurement. Art’s value lies in its ability to catalyse change, in the lives of those who make it and encounter it. It is a process that proceeds over time, with repetition and inflection. “Liking,” “+1-ing,” and “retweeting” are not responses, they are convulsions that stand in for an encounter we wish to have. The Me generation has given way to the “me-too” generation.

When the mechanisms of response are so rudimentary, when the metrics of momentary attention trump all other assignations of value, where does that leave us as makers? For many, the internalization of the advertising mindset is complete as they struggle to “manage personal brands” across multiple online forums, or try to drive their numbers up. In part this is because it’s easier, less painful to talk about the amount of something than the often contradictory or ambiguous meanings that happen with each encounter.

The only future of art that I’m interested in lies in the cracks, the spaces between screens, or where our encounter with screens is made once again slow and strange.

Nayland Blake is an artist and educator who lives and works in Brooklyn.

Anney Bonney

Disambiguate the Present

Disambiguate is a word that always stops me. It’s not an everyday word. I don’t hear it in conversation but it lives within the collective screen of Wikipedia. So actually, it is an everyday word. I spend time with it during every visit.

Disambiguate . . . ‘Remove ambiguity from.’

. . . forming adjectives and nouns with the sense ‘both, on both sides, both ways.’

Agiere: Latin for ‘drive’1

Ambiguity carries the seeds of its undoing in its unfolding. When I read disambiguate I know it asks for more clarity but I feel alienation and dislocation — more confusion. My limited research suggests the word comes from nowhere, and has no specific date of origin, perhaps the sixties. How perfect. Extend its latent sense of drive to Freud’s concept of Trieb, life force, instinct and there’s a desire to know both sides tucked neatly inside its negative equation.

People walk with their cell phones in hand, like heat seeking magic carpets ready for transport. Look both ways to navigate the flood of hyperactivity, hyper image/text reality. This functional displacement has not made us hyper aware or more present. The needle pulls more toward accelerated relocation in denial/paranoia.

That shift is easy to date . . . 9/11/2001.

After the towers collapsed I found myself going to the site late at night like a video sleepwalker on call, spirits rising out of the gothic ruins. I talked to policemen drinking coffee. I thanked tired workmen who rode up high in cable cars. They sparked fire bright displays with their acetylene torches. Being thankful seemed important.

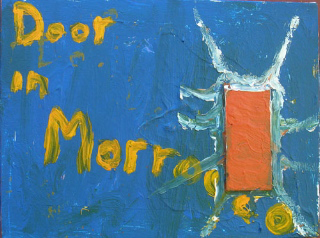

Anney Bonney, In-Ra-In, 2011, digital print on rag paper, 24" x 34".

I didn’t know what else to do but document the mayhem aftermath in some skewed personal way. I lived with toasted cars and Pompeian dust. I smelled the rubber and refuse burning for a couple months. The towels that cased my inside windows turned acrid yellow.

One of my students recently wrote, “it’s a great time to be alive because everyone can be an artist. Everyone has an iPhone.” While I appreciated his optimism I wanted to blunt the argument and refer him to Jaron Lanier’s You are Not a Gadget: A Manifesto, but he dropped the class.

It’s a consequence of pronominal culture. iMovie, iPod, YouTube present a world of devices, apps and Internet services based on you and I (or me or my), the intimate Faceless interFace that promises uber creativity.

Watch people texting madly. It’s serious business living in the social paradox network. We have never been so many, so connected, so informed: we have never been more alone. The ideology of privileged technology can give voice to dissent then lose it in ambient chatter.

There’s only one Ai Weiwei.

What happens to artists whose work avoids Internet media spin? To make something with your hands that rejects the model of artist as entrepreneur is a step way outside consensus. Knowing that something you make might transcend its materiality insults the hive mind. It honors the life of the individual encountering his/her work as its own world. Does that experience have to be degraded as self-indulgence? At least there’s a palpable self to indulge. Can’t it be heroic — again — for reasons other than its past?

I have a friend who’s been painting abstract inscapes for 30 years. He says life in New York has become a vortex, spitting out whatever it can’t engorge in conformity. Certain poets and painters are ejected by the centrifugal force of its consuming whirlpool. They are the first wave to lose support. They are the first to go.

I empathize. Without independent spirits, art and artists die. I concede I need techno/web tools for video, printing, designing, writing, teaching. I am only free when I am light/water, painting and dreaming. My thought-forms on exponential change are neither U- or Dys-topic. I could leave the planet when it seems aimed at Kurzweil’s singularity. I remain curious.

Ambiguity can inspire by double meaning “admitting more than one interpretation” or frustrate when it’s leveled to “unreliability.” I will hold a place for mystery, the unknown, listening, watching, looking both ways, living on and not forever.

1. The sixth edition of the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on historical principles.

Anney Bonney is an artist living and working in New York.

Jackie Brookner

There are acute traumas like 9/11 and the current American wars — acute in the medical sense, meaning very severe, but of relatively short duration. And then there are chronic traumas that persist over a long duration with a low background drone, occasionally punctuated by what seems to be an acute eruption. The deterioration of all of earth’s natural systems, climate change, and mass extinctions of species on land and water are of this latter sort. (And they could, without too much difficulty, be considered a root cause of 9/11, the wars, and the recession, driven as these are by the hungers of the oil economy.)

I work with water, and people — trying to affect change at the practical level, by creating systems that clean water, mostly urban stormwater. Because I want to affect change at the level of causes rather than symptoms these systems are very intentionally art. But how can art do anything about huge systemic problems like water pollution, rising sea levels or climate change? Ultimately it is what we care most about, what we understand to be in our own self-interest, our values, that fuel these problems. To get to them, you have to affect people at the levels where values are formed — a bit in the head, but mostly in the heart, and at the kinaesthetic and less than conscious levels. Ultimately it’s a question of who we think we are. And who is “we” is much to the point.

Over the past several years, the need to push back against the docility and passivity of this culture has been pressing upon me. The work has been focusing more and more on creating processes and situations where people in communities can experience their creative agency, and experience their power to do something that directly affects what happens with areas of land and water in their own neighbourhoods. My interest in individual authorship has waned in direct proportion as this public focus has become more defined. I am much more compelled by working together with other people to budge our species in the direction of long-term survival — if that is possible.

I weaned myself from the art market and fashion and their fixation on individuality and idiosyncrasy long ago. Fortunately I have found opportunities to work in the public realm and with communities, where the work needs to be done.

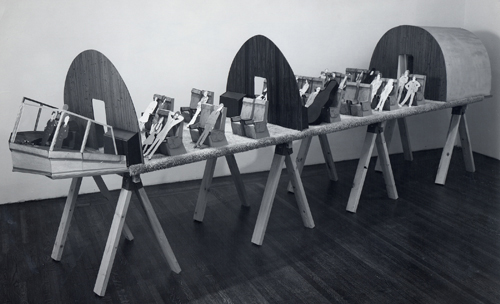

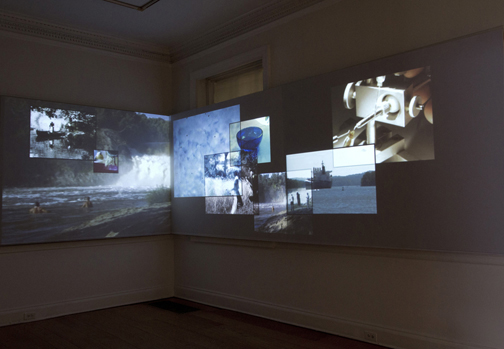

Work by Jackie Brookner, in collaboration with Tuula Nikulainen, residents of Salo, Finland, Salo Parks Department, Salo Office of Environmental Protection, BioMatrix Water, and students and faculty of the Salo Polytechnic Institute.

Veden Taika (The Magic of Water), 2007-2010. Three floating islands that provide safe habitat for nesting birds and plants to clean pollution in the water and sediment in a former sewage treatment lagoon in Salo, Finland. Dimensions: central island, 98.5 x 21 feet; 2 smaller islands: 39 x 20 feet each. Islands: plastic pipe, plastic mesh, gravel, geotextile, wetland plants. Sculpted rocks: styrofoam, lightweight concrete. Images show the islands from different views and the students working on the island structures.

Jackie Brookner is an ecological artist and writer who works collaboratively with ecologists, engineers, design professionals, communities, and policy makers on water remediation/public art projects for parks, wetlands, rivers, and urban stormwater runoff. Her current project, The Fargo Project, was awarded an inaugural “Our Town” grant from the NEA.

Joyce Burstein

Zombie esthetics or how to survive the trauma that has always been eating our brains

My first thought was that these traumas have always been there beside us. A childhood backgrounded by the nightly news with scrolling names of local soldiers perished in Vietnam, the terror of the draft numbers, my grandmother aghast at Israel’s war on Palestine whimpering, “but that’s what the Poles did to us,” the first time I was old enough to vote, Reagan’s acceptance speech, his speech at Bitburg, the hostages, one of whom I went to high school with, Zimbabwe, El Salvador. These traumas we stare at on the TV. There are those who curled up in a ball of fear after 9/11 and I understand that pain is relative, but I also see reaction relative to how politicized one may be — if one has “occupied” themselves with power structures, it sort of never leaves you completely passive again. I’ve been arrested a dozen times for civil disobedience, lobbied state legislatures, and laid down in front of bulldozers — for me when the planes hit I go into last girl mode.

Stretch, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, 1986, Tobe Hooper.

For those of you with something more refined than the cinematic esthetic of a 14 year old, Stretch is the one that survives in the horror movie, not just survives but somehow in between the running and the hiding and the killing transforms her fear into strength and then she doesn’t even have to kill the monster — it’s rendered irrelevant by her mere survival but she offs it anyway — or to be continued. I see this condition of public trauma being played out relentlessly, continuously, akin to the allegory of the zombie genre, some say the only new myth, born as an allegory of slavery and loss of identity in voodoo culture and delivered to ours as the slavery of consumerism and the only way it can frame my relationship to production is to not get bit. Everything about the art market is infected, it’s part of our zombie economy — parasites that consume without contributing. Didn’t art die in the 80s? Post-death, the slouching corpse who proceeds as if the miracle of the ’70s never happened. Don’t get bit, don’t even get a scratch. Make it too big to sell, use choice as a weapon, ethics over esthetics, viewers over self, mind over eye, community over competition, because as Columbus says from Zombieland, “without other people you may as well be a zombie.” Cultural production? Who has time what with all the running and hiding (so much hiding) and the head shots. Born into a world alienated from its production, graduate with MFA debt rendered unemployable until recently. Try getting a teaching job with employers contacted by the attorney general to write 1/3 paycheck to the government. Stuck with under the table jobs like digging ditches out of the intricately banal traumas of living in a mindless society continuously buried alive under a mountain made of mole hills and digging out. How to defeat the inner zombie?

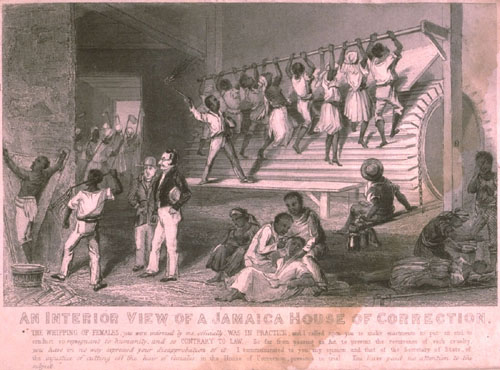

An Interior View of a Jamaica House of Correction, c. 1835.

My particular idiosyncrasy — fantasizing screenplays of who will survive a zombie attack at art events, like a gala I got taken to at the Guggenheim, a museum I can rarely afford to even enter. Because we know there is strength in numbers, who to follow? Amidst the carnage of the glitterati of the art world, bands of survivors form, one led by Carolee Schneemann who, like a feminist MacGyver, through resourcefulness and wits can escape structures that defy or define her, or Matthew Barney, who despite intimate experience with the territory must form a production crew and mediate the ideas of others, sadly money means nothing in situations like this or there is Marina Abramovic’s endurance and the stealth of letting go of ego, empty the vessel and out zombie the zombie. I would follow Schneemann, of course, while scouting my own weapons — damn these museums with their outmoded focus on painting — a Renoir’s no good for beheading a monster.

The art market’s role is both fodder and cause of the outbreak, in my scenario it’s the artists who avoid complicity with the market that survive.

So we’ll occupy Wall Street and we’ll occupy museums right? Because we’re not scared of death we’re scared of slavery.

Joyce Burstein is an artist living in NY who saw her first zombie movie at MOMA in the early eighties. She is teaching Feminist Art and Culture at SUNY New Paltz, a recent job that feels like bathing in diamonds.

Sharon L. Butler

Free Love

Consumer advocate Martin Lindstrom wrote in a New York Times op-ed recently about a casual fMRI experiment he conducted with smart phones. Testing sixteen participants (eight male, eight female), Lindstrom expected the experiment to reveal that we are addicted to our smart phones — that when the phones buzz, ding, or ring, our brains respond as they do when stimulated by drugs and alcohol. Instead what he discovered was that phone activity led to movement in the brain’s insular cortex — the realm of feeling, love, and compassion. Lindstrom concluded that we aren’t addicted to our devices, but that we love our gadgets the way we love a romantic partner or family member. I would suggest that perhaps we don’t love the gadgets per se, but that we love the feeling of being loved that their apparent attentiveness continually provides. Each ding or buzz indicates that someone is retweeting our tweets, sending us a note, or “liking” our status on Facebook. An iPhone doesn’t actually give us the love, but it transmits it.

For artists, the majority of whom will never experience sustained critical attention or receive financial compensation from their art practice because the odds are stacked so overwhelmingly against their commercial success, social networking tools are invaluable positive reinforcement. They have enabled artists to build sustainable art communities with broad reach outside the traditional commercial gallery structure. It’s not just the constant flow of Lindstrom’s love that has driven artists into the arms of Web 2.0 and social networking media. Free tools like Wordpress, Blogger, Facebook, Google Plus, and Twitter that intensify our desire for smart phones are particularly important to unrepresented artists who have customarily been excluded from the critical dialogue. Artists armed with only social networking media are taking greater control, and this is changing the way the art world works.

In 2007, when I started Two Coats of Paint, an art blog dedicated to painting and related subjects, I recognized that the availability of these free publishing tools was historically significant, but established writers and mainstream media, dismissive of blogs in general and especially unvetted bloggers, were slow to understand the immense impact blogs and social networking media would ultimately have. As recently as last year, Malcolm Gladwell published a piece in The New Yorker arguing that the use of social networking media actually inhibited our ability to affect real political change. Shortly thereafter, the Arab Spring, which was unequivocally facilitated by the protesters’ use of social networking media, proved his thesis completely off the mark.

Sharon L. Butler, Cage-building, 2011, silver Krylon on unprimed, unstretched linen, 72" x 60".

Interestingly, not all artists agree that social networking media constitute a positive development. I recently received an email from an art PR firm outlining a project that Danish artist Thierry Geoffroy has organized at the Sprengel Museum Hannover. In the exhibition statement, Geoffroy suggests that artists “should not let social media dominate the field of collecting the history, images, feelings and interactions of human activity. The museum should regain this stolen territory to prevent the world’s archives from ending up in the hand of companies with domination goals.”

At first glance, his argument seems compelling. After all, what do Google and Facebook know about art? And shouldn’t we be dubious of mob rule, especially when it comes to our cultural legacy? On closer examination, however, most artists might be better off embracing social media, which place power in their hands, than they would be in maintaining fealty to museums and galleries whose exclusionary practices are wide ranging and well documented. As part of the existing art industrial complex, museums are funded by corporate interests and wealthy collectors, and will only give artists the love if the artists have a strong enough voice to demand it. Relatively few do. But creating an online soapbox is a good first step.

An artist and writer, Sharon L. Butler blogs at Two Coats of Paint.

Tom Butter

Film Eats Everything

Film eats everything. Over and over film asserts itself as the dominant medium, it consumes and alters everything it touches. Art now aspires to the condition of film. Novels are increasingly cinematic. Performance art is a kind of “live” film, expressing all the structural distance film has — pushing the audience away, unlike the shared experience of theatre, where something is built with the audience’s tacit approval. Sculptural installations in galleries and museums often feel like film sets, putting people in their own movies. This is thrilling. We assume auras of stardom walking through spaces built for temporary use. These constructions move us into the role of actor. Installation art isn’t architecture, or sculpture, but makes a temporary space in which to perform, generating a need for our presence, seducing us.

The influence of TV and film on the broader culture is everywhere. Film is the 20th-century virus infecting all culture. Facebook allows us to become persons with public lives on display, lives full of minutiae and drama. We are our own publicists and paparazzi, we become movie stars! The shimmering world of public image and celebrity is available to everyone, and as a consequence our lives become more “real.” They are part of an endless happening, the endless present that the Web brings right into our homes.

In 1953, in an appendix titled “A Note on the Film” in her landmark book Feeling and Form Suzanne Langer applies her analytical skills and intuition to what she calls a new art. She situates film in the spectrum of other media, coming up with its primary illusion — virtual history expressed in its own mode — the dream mode. And in this mode, film creates a ubiquitous virtual present, or as she puts it so well in the last three words of her book: an endless Now. In a very few pages Langer captures the pull and psychological power of the medium, the way it works and what it does for us.

What could be better than an endless Now? With kids, the immediate, locked-down fascination with television’s moving image is palpable. They merge with it. My generation, composed of the first kids raised with TV, is fascinated with moving image media. TV has been the subject and the foundation for much of the art we have made. I think the pervasive irony found in much art made today comes from the sense, as kids, that as we watched these ½-hour comedies or 1-hour dramas we were made to feel and think things without directly being part of them, or having control over them. It was, following Langer, as if we were dreaming them. And these TV shows would resolve everything neatly in the given time frame. Because kids want to know how things work, we stepped back and looked at the mechanisms and machinery of these representations. We thought about how these moving images could get us feeling and thinking certain ways. Our deciphered understanding of the cheesy methods used in these shows created distrust of the notion of value in culture. We developed a need for distance and cool in our work. At the same time we felt a compulsion to repeat the methods absorbed so early. We learned that life is not to be felt and lived, it is to be decoded and thought about in terms of standard patterns of behavior, using quick, schematic, predetermined relations between people as the norm. What a climate! It isn’t hard to imagine why we formed all sorts of cynical conclusions.

But there is another side to the development of film and TV as dominant media of our time. Film’s ability to produce an “endless Now” has the potential to liberate us from our lives, to literally get us “dreaming” about things we don’t know. The experience of watching film can distance, but it can also connect. We always have the choice with culture, even when it doesn’t feel like it. Today, with social media seeming to move us in one direction, we can choose to move in the opposite way. Viewing early Herzog films we enter new worlds and leave the theatre changed by seeing people do what they do under duress, in strange circumstances. To watch Joe Morton play an alien in Brother From Another Planet is to review all the things we take for granted as humans — for example: not putting ice in beer! Seeing Michelle Pfeiffer playing a jazz singer devoted to her art in The Fabulous Baker Brothers is to understand what work and commitment can mean to an artist over the long haul. Michael K. Williams playing Omar in The Wire gets us thinking about what it means to live by a code. The brutal impingement of the physical world on the characters in Runaway Train is unbearable but oddly cleansing. Watching Jack Nicholson’s character in The Last Detail try to give Randy Quaid a feel for how he lives life is a heartbreaker. These films open the world. The dreaming adds to our lives, we expand. . . .

Tom Butter has been showing his work in New York City, nationally, and internationally since 1981. He has published articles in Whitehot Magazine, The Brooklyn Rail, and is currently teaching in the MFA Fine Arts program at Parsons the New School for Design.

Anna Chave

A day or so after 9/11 — when I witnessed the second tower’s collapse and then stared at the phalanx of ghostly, shell-shocked Wall-Streeters streaming past my front window on the Bowery — I had to go as usual out to Queens College to teach. I was meant to lecture on landscape and nature imagery that day in my History of Photography course, including the surpassingly romantic work of Ansel Adams and Edward Weston, who mostly photographed the Western U.S. during the Second World War as if they had never got the news. I did consider switching it up, jumping ahead to documentary work, zeroing in on war and crisis photography, but I finally decided against teaching material for which the students were unprepared. Yet it seemed an absurdity, if not an obscenity, to be discoursing on exquisite images of sand dunes and green peppers as the World Trade Center smoldered not far away and desperate people cased the city in vain hopes that their family members had eluded unthinkably horrible ends. So I halfway apologized to the class, when it convened, for proceeding with business as usual. But the class surprised me with a (unprecedented) round of applause at the beginning and again at the end of the lecture. And one of my most serious students — namely one of my “Greatest Generation” auditors — said to me afterwards that Weston and Adams had been, after all, just right for that dreadful moment: everyone had needed more than anything to be transported, and so they were.

When circulating outside the art world, among people who don’t generally meet art historians, I find that their dominant notion about my peculiar vocation is that I must lead a fortunate life. And I acknowledge that I do. But going on four decades into this field, I sometimes add that, although the art world has become appreciably more global in recent decades, it can still seem a lamentably parochial or marginal place, especially at times when the larger world is coming conspicuously unglued. And the response I almost invariably get is this: What better times could there possibly be to have the job of bringing art to people and vice versa? — a response that always takes me back to the warm reception I got for my apparently, utterly irrelevant lecture following 9/11.

Much as I admire 20th-century and contemporary artists who find ways to do effective political work through their art, I seem to keep getting brought around to this reality: that the public doesn’t tend to look to art, in the first place, for its political efficacy. Speaking generally (or through my proverbial hat), inasmuch as people feel that they need and want art in their lives, it often seems to be as an avenue to remove them from the world’s more frustrating or galling realities, while returning them instead, in other ways, to their senses. Those of us who tend to view art through political lenses may lose sight of what else it is that art does or, I will venture to add, of how — precisely by returning people to their senses — the things that ostensibly non-political art does may have their political valences after all. Just so, those mesmerizingly sensual photographs of Oceano Dunes turn out to look compellingly, hauntingly post-apocalyptic when viewed at an apocalyptic time.

Anna Chave is known for her revisionist readings of Minimalism and for her writings on issues of reception, interpretation, and identity, on subjects ranging from Brancusi, to the Gee’s Bend quilters, to Hannah Wilke. Much of her work may be accessed at annachave.com.

Daryl Chin

It seems obvious that events in the real world, especially in terms of cataclysmic occurrences, must affect the life and work of artists, yet it would be foolhardy to believe that the correlation is simple. Art must reflect the truth of an artist’s life, but that does not mean art must merely mimic the outer conditions of the world. Without the impetus of imaginative transformation, the work is not art; it may be reportage, it may be documentation, but it’s not art. Yet we live in a time in which the very terms of art have become so destabilized that there is no longer any idea of cultural tradition or aesthetic standards, which might have proven to be all to the good if the societal underpinnings of culture hadn’t also eroded.

Critical practice has devolved into two distinct (and equally uninspiring) realms: there is the journalistic prattle of art as commerce, with an emphasis on auction prices, the art market, and commercial value; there is the theoretical blathering of academia as critique, with its equally desultory de-emphasis of art. But this situation has been going on for more than three decades, and does not look to be changing any time soon. Nevertheless, one can always find isolated moments of genuine aesthetic inquiry. But what one can’t find is the sense of continuity which comes from a community of interest between artists, critics, and audience; it’s far more fragmentary and individualized. Yet the interest in art remains intense, even if diverted through marketing, commercialism, and ideology. For all the external distractions, there remains an audience which continues to seek out the aesthetic experience. And no matter what form that experience takes, the indispensable aspect of art is its manifold demand on our attention, our consciousness, our emotions, which can sharpen our sense of our place in the world.

Getting personal: growing up in New York City in the 1950s and 1960s, I was very aware of the artistic community which seemed omnipresent, certainly in lower Manhattan. Perhaps because of the proximity of artistic practice, artistic endeavor didn’t seem alien, it seemed an entirely appropriate choice. Soon, like many others before and after, I became a part of the artistic community of lower Manhattan, first as audience, going to galleries and performances and films, then as practitioner, initially as critic, then as artist. Since I worked in performance, and not as a solo performer, art became a form of communal activity. But the sense of community remained very strong. Gradually, there was a dispersal, as lower Manhattan was transformed, people were displaced, and the community was irretrievably shattered. Can the erosion of the downtown aesthetic be pinpointed to a specific date? Was September 11, 2001, a turning point in the destruction of lower Manhattan? Does the incessant amalgamation of corporate greed located within the precincts of lower Manhattan affect the devolution of artistic practice? Suffice it to say that, all my life, I was confronted with an artistic community in constant permutation, then I became aware of the disintegration of that community.

As the 21st century began, so did the advances in media technology that brought the rise of social networking. When Facebook made its appearance a few years ago, I joined because the people who invited me to join were friends who had moved overseas, specifically to Hong Kong, and this seemed a way to maintain some sort of contact. And soon, I was back in contact with people I used to be close to, people I would see every day, people who had lived and worked near me, but were now in other parts of the country, or were in other countries. So the dispersed community seemed to reconfigure itself in a virtual reality, but this community seemed chimerical, even spurious. The various social networking platforms (first MySpace, then Facebook, plus sundry others such as LinkedIn) plus e-mails, Skype, iPads, iPhones, texting, et al, have all contributed to the virtual community, however nothing can quite take the place of the actual person-to-person communication which was crucial to the artistic community of lower Manhattan during the 20th century.

Daryl Chin is a writer and artist, now living in Brooklyn. He recently spent 10 months as a Fellow of the International Research Center: Interweaving Performance Cultures of the Freie Universitat Berlin (October 2009 – July 2010). He maintains the blog Documents on Art & Cinema.

Jennifer Coates

Etherites

In thinking about the artworld from an artist’s perspective, it’s important to remember:

1. You are puny.

2. Your ideas are runny like soft-boiled eggs — also, like soft-boiled eggs, they have probably occurred before.

3. You will not ever succeed, but once in a while you may get a swelled head and think you are magical.

4. People will want to bite you.

5. You will want to bite them.

This is an excerpt from one of the first posts on my now-defunct blog, Artistic Thoughts, circa 2005. There was an all-consuming, unstoppable fantasy world that developed in the burgeoning blogosphere of that time. My involvement in it started one day when my friend, artist Sarah Peters, and I decided we needed stir up some mischief. We were reading Martin Bromirski’s blog, Anaba, which at the time was based out of Richmond, VA. Martin was dogged and thorough about posting other artists’ work. His descriptions and observations were in the first person, there was no attempt at art jargon. He presented a readable, relatable personality. He discussed the unfairness of the artworld, the experience of being an artist working outside of New York, and he was honest in his resentments and irritations. His public declarations felt dangerous and contagious and so we decided to start a blog of our own. Except we immediately knew we needed a pseudonym. There is something freeing about an alter ego. We agreed on the moniker Mountain Man, which was the subject of a fake essay I had written a few years earlier entitled “Mountain Man: A Thing of the Past, Present or Future.” (Don’t ask.)

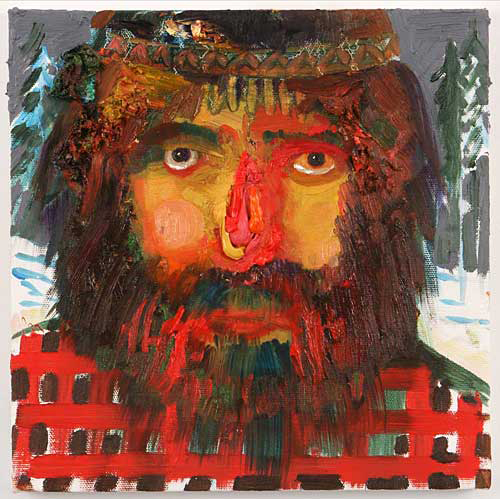

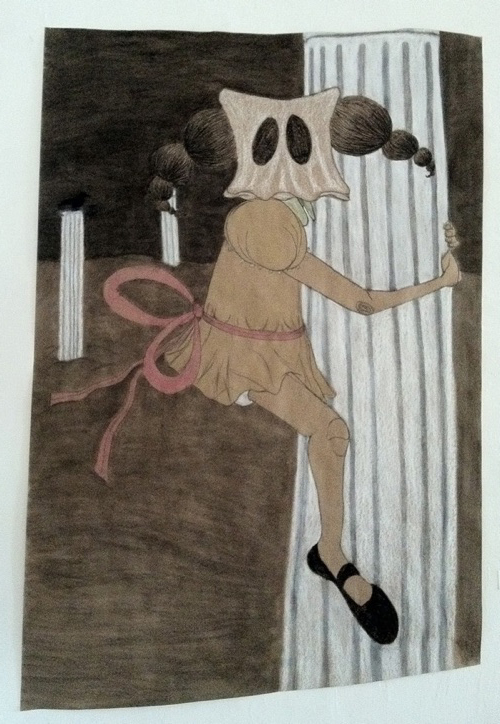

Nicole Eisenman, Mountain Man, 2006, oil on canvas, 12" x 12".

Mountain Man was disgruntled. He was tall, had long hair, and wore stained shirts. He was a pervert and a visionary. He had an office job where he made sculptures out of staples and pencils by day, constructed towers of toast in his living room by night. The blog started out being loosely about disappointing shows he saw in Chelsea, the competitiveness of the artworld, and various people who tormented his sense of self. As we began fleshing out Mountain Man’s character, we gave him a girlfriend, an alcohol problem, an airstream, nudist tendencies, a propensity towards rubbing against inanimate objects, and a marked inability to discern imaginary from real.

After a few weeks, we shared the blog with some friends, just to see if it was funny to anyone else. Little by little, friends started to comment, sometimes anonymously, sometimes under their own pseudonyms. They started their own blogs and began fleshing out their alter egos: Fairy Butler, Postmodern Debunker, Sloth. Sarah eventually split off from Mountain Man to develop the amazing character Ham Paw, a tender ecstatic who could spontaneously intone like a cult leader but with the cuddliness of a stuffed animal. Slowly but surely an imaginary realm evolved from conversations about art we saw, art we made, our existential traumas, and the banality of everyday life.

We would envision ourselves under the concrete slabs of the sidewalk, flying around on a magic deli meat slicer, wearing costumes, and sipping magical potions. We spoke in code, renaming our studios “shacks,” our artworks “relics,” and office jobs were “the beige.” Our interactions were dense with visions, dreads, complaints, and most importantly, words of support and encouragement for each other.

Sarah Peters, The Seer, 2005, pen on paper, 14" x 11".

We began commenting on other art blogs that looked interesting: Wendy White, Militant Art Bitch, Nicole Eisenman’s A Blog Called Nowhere, Painters NYC, all the while collecting new acquaintances and a widening readership. There was something magical about connecting with other artists through disembodied comments that were delivered in veiled and absurd language. It was so compelling it sucked me in for hours a day, and there was an ever-expanding array of characters: Lupin, JD, Gree C. Hair, The Gaylord Rehabilitation Center, Sea Monkey, The Capt’n, Krixfort, Uncle Fritz, Heart as Arena, Sushi Blameful. And many of us had other temporary identities, any number of characters to suit any mood.

I enjoyed the psychological metaphor that the blog post personified on Artistic Thoughts. It was like a super-condensed version of a self amongst others. I would assert an idea, a reverie, some ridiculous claim, often associated with an image or set of images, and then wait for responses. If none came fast enough, I would just invent characters and talk to myself. Sometimes I’d have conversations with characters I didn’t recognize — they could have been friends or strangers and it didn’t matter. The lack of clarity was pleasant; the confusion of identities was disorienting in the best way. It was basically extended make-believe play for adults.

Jennifer Coates, Ruin, 2011, acrylic on canvas, 24" x 30".

Unfortunately, the more readers we got, the more we were subject to nastiness. For me, this was a deal-breaker. Reality caused the experience to curdle as “trolls” and anonymous haters changed the ecosystem. Despite the fleeting nature of the blog arcadia, lasting relationships formed. The ether is an amazing place to come into contact with images, information, and people that you wouldn’t normally encounter in everyday life. But I’ve come to see it as just a path on the way to so-called real experience: I am committed to seeking out the person behind the moniker or the object represented by the JPEG.

And anyway, somewhere outside the time/space continuum we Etherites remain hyper-dimensional objects permanently at play: wearing MC Hammer pants, growing horns, and communing around a hot dog totem.

Jennifer Coates is an artist, writer, and fiddler living in NYC.

Maureen Connor

Based on my sense that artists are uniquely positioned to gain trust and encourage positive change in organizations and institutions I have been ‘embedding’ myself within them (as a de facto artist in residence) for more than a decade. Most recently, together with the Institute for Wishful Thinking (IWT) a collaborative I cofounded in 2008, we’ve been working as Artists in Residence for the US Government (self-declared). The IWT believes that the community of artists and designers possesses untapped creative and conceptual resources that could be applied to solving social problems. With this in mind we are soliciting proposals from artists, architects, and designers for residencies at government organizations and agencies at all levels. Since last we issued the call last spring we’ve received more than 50 and still counting.

Kenneth Pietrobono, Proposal for the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior National Mall & Memorial Parks, the creation of a ‘National Rose Garden’ within the National Mall. Given the power of the National Mall as a setting to “celebrate the US commitment to freedom and equality” all hybrid roses are given names that reflect the systems and policies we cultivate in this country in the name of and denial of ‘freedom and equality.’

I’m certainly not the first to develop embedded work. The Artists Placement Group ‘placed’ artists in factories, offices, and other work sites beginning in the late 60s and since then a short but growing list of artists have worked with similar methods and goals. There need to be many more essays and books written about artists who have engaged with and continue to develop forms of direct institutional intervention from the inside (as opposed to using resistance and protest) with the goal of positive social change.

This work awaits new methods of interpretation. Up to now it has been mostly hidden away in appointment-only archives or written about by critics who expect it to conform to irrelevant criteria — and those are the well-known artists!

In his 2004 book Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art, Grant Kester lists embedded art practice as one of a number of forms he calls ‘dialogical art,’ which “share(s) a concern with the creative facilitation of dialogue and exchange” while my colleague and collaborator Gregory Sholette labels such practices ‘dark matter’ in his 2010 book Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture. However both concepts encompass a broad range of models for socially engaged art that extend far beyond embedded practice. Marisa Jahn’s 2010 book Byproduct: On the Excess of Embedded Art Practices does focus specifically on the kind of work under discussion here.

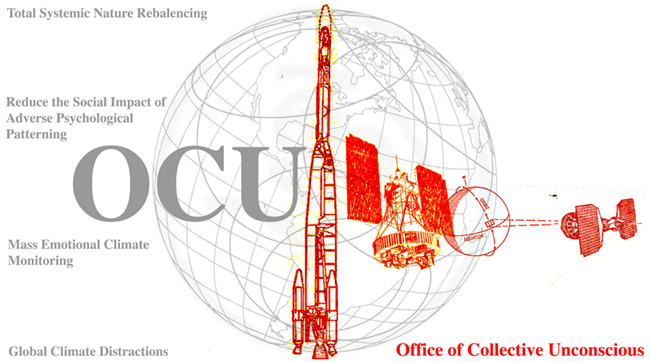

Nsumi Collective, Proposal for the Office of Collective Unconscious, a new office for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration for mapping and processing the collective unconscious of the USA through

the deployment of psychospheric instruments.

Molly Dilworth, Proposal for the Department of Energy Weatherization and Intergovernmental Program & NYC Department of Buildings — Cool Roofs: A series of solar reflective rooftop paintings.

In an effort to contribute to the discourse that engages with these ‘fellow travelers’ I will presume to ascertain some common ground. Perhaps we should call them the five danger signs of impending embedded practice:

1. A shift in ambition: slowly (or suddenly) the white cube seems to demand conformity rather than offering autonomy.

2. The emptiness of market-based art discourse contrasts with increasingly dire social problems.

3. Artists look for sites in which their critical eye can be put to a more productive use.

4. Location, location; as artists we learn that context is everything. So how to reframe an art practice? Look for an audience that will have little to no understanding of your work.

5. Try to figure out a way to make what you do useful to that audience.

Maureen Connor is a visual artist whose work combines elements of installation, video, design, human resources, and social justice. As part of a collective, the Institute for Wishful Thinking, she is currently the (self-appointed) artist in residence for the United States Government.

Patricia Cronin

Dante’s Inferno: The Way of All Flesh

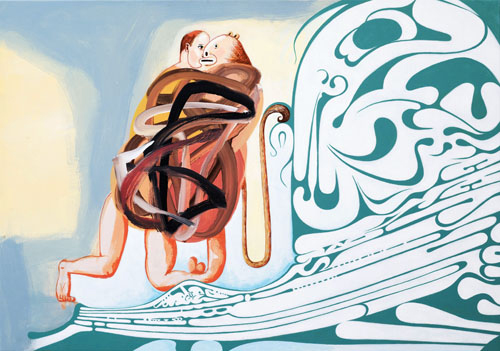

From 2000 to 2009, virtually the entire time George W. Bush was president of the United States, I worked on two main projects with strong social justice themes, specifically gay marriage and women’s history. Since 2010, I’ve been working on a series titled Dante’s Inferno/The Way of All Flesh. It is a cycle of oil and watercolor paintings inspired by Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, a timeless story of moral frailty.

This project uses the Inferno as a point of departure for an extended meditation on the human condition. For me, the Inferno is ripe for artistic re-interpretation in our post-modern world, where many of the same social issues — war, corrupt politicians, religious hypocrisy and strife, unstable economic markets, and natural disasters — still plague us.

Patricia Cronin, The Lustful: Canto V, Circle Two, 2010, watercolor and metallic watercolor on paper, 60" x 40".

Inspired by 14th- and 15th-century illuminated manuscripts of the Inferno, artistic interpretations from the 16th through 20th centuries, Italian fashion photography, and tracings of my own body, these life-size “shades” as Dante refers to sinners act out a classic cautionary tale that has largely gone unheeded.

Dante’s Inferno/The Way of All Flesh connects with my first decade of works that examined the erotic in the everyday (watercolors of intimate sexual acts as well as performance-based photographs) and extends my line of art historical examinations of the past decade (Memorial To A Marriage, my marble mortuary sculpture installed in Woodlawn Cemetery, and the watercolor meditation on the works of 19th-century sculptor Harriet Hosmer in the form of her catalogue raisonné).

Patricia Cronin, Shade, 2011, oil on linen, 64" x 46".

Oil paint has endured as a valued art medium since the 15th century and I’m drawn to the chromatic optical qualities unique to paint. Combining them with a timeless story from the same era, I’m re-imagining the rise of humanism. In this “winner take all” climate we live in, the spirit of generosity and the concept of good citizenship seem to be all but lost. How do we think about our fellow citizens and our shared common humanity? And what will we do about it?

Patricia Cronin is a New York-based artist and Professor of Art at Brooklyn College of The City University of New York, whose work has been exhibited extensively in the U.S. and internationally including at: David Zwirner Gallery, Marlborough Gallery, Yale University Art Gallery, the Neuberger Museum, and other venues. She has had solo exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum, Deitch Projects, and Brent Sikkema.

Jennifer Dalton

Some Paradoxes that are Likely to Remain Unresolved*

I want to overturn the system but in the meantime I want to succeed within it. I hate the art world, but I love my tiny corner of it. I should stop making art, or I should stop doing anything else. I want to sell my work but I don’t want to part with it. I think of art as a gift but I don’t want to work for free. Or, often I am willing to work for free but I don’t want to be exploited. I think money corrupts except when I have some. I hate shopping but I like things. I want my work to be owned by people without tons of money, but I can’t afford to sell it for cheap. I don’t want art to be elitist, but I distrust mainstream tastes. I prize tolerance and acceptance of others unless you disagree with me politically. I want to succeed, but I’m terrified of success. I want to be noticed, but I don’t like being the center of attention. I value feedback, but I hate criticism. I distrust anonymous blog comments except when they are saying that I suck. I think I should trust my instincts, but I’m afraid they will lead me to shoot myself in the foot. When I am afraid of something that usually means I should do it, except when it means I shouldn’t do it. I am a loser and I am a pig.

* Inspired by the conversations of #class, a month-long series of events and discussions at Winkleman Gallery presented collaboratively by William Powhida and me in February–March 2010.

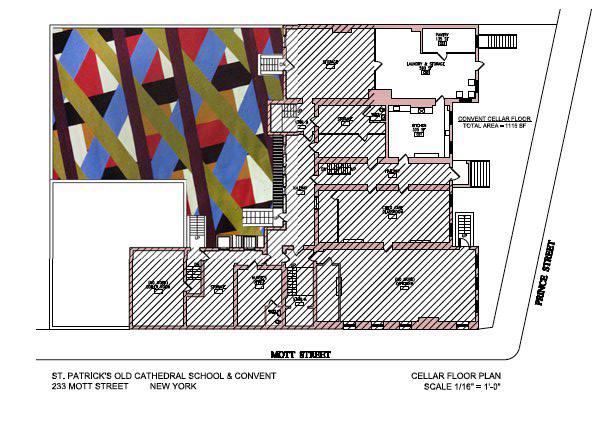

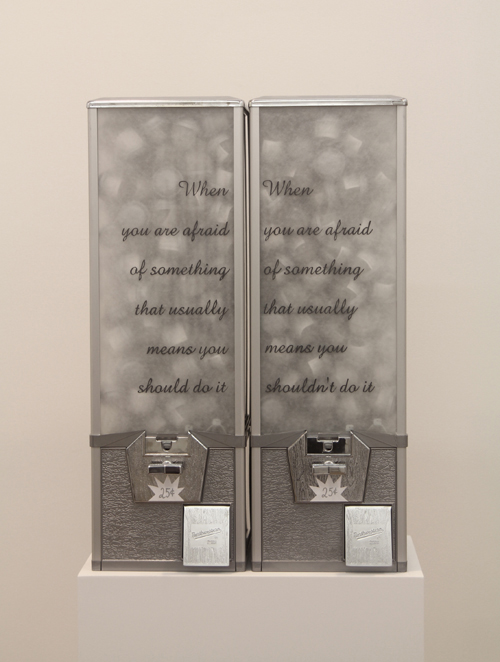

Jennifer Dalton, Only in America, or, I Can’t Trust Myself, 2011, vending machines, plastic capsules, temporary tattoos, on wood pedestal, 68" x 22" x 12" (overall).

Jennifer Dalton is a Brooklyn-based visual artist. Her most recent exhibition was Cool Guys Like You at Winkleman Gallery in New York.

G. Roger Denson

Won Over? Or Winning the Community, Production and Distribution of Digital Corporate Conglomerates?

After taking a ten-year hiatus from art writing (1999–2009), one I’d intended to be permanent, I found myself unexpectedly returning in 2010. I did so for one reason only: the expanded opportunity that e-publishing presented for producing and disseminating writing more relevant and timely to the contemporary political and social landscape.

The art trade press I wrote for throughout the 1990s was, as it is still, dictated by market entities: the galleries that take out ads; the auction records set; the blue chip artists that make collectors salivate. There’s always a measure of the market reducing art criticism to ad copy in the trade publications. Then, too, editors such as Betsy Baker at Art in America, Stuart Morgan and Michael Archer at Artscribe International, Bice Curiger and Louise Neri at Parkett, Helena Kontova and Giancarlo Politi at Flash Art, Thomas McEvilley at Contemporanea, Barry Schwabsky at Arts, and Eri Kawade at Bijutsu Techo imposed their formidable imprimaturs on all content, critical methodology, even reference notes, according to their magazine’s relationship to the art market.

To write about larger cultural and political concerns outside the purview of these magazines, I turned to non-trade publications such as M/E/A/N/I/N/G, in which I wrote on the relationship of identity politics in art and politically transgressive mythopoetics in the superhero, cyberpunk, sci-fi, and vampire genres. Similarly, in Acme Journal I could write about globalism, cross-culturalization, and nomadism. But as welcome as these publications are, my audience was even more restricted by the limited circulation of these journals, and to find platforms to support my wider cultural and political interests, I had to submit articles to unfamiliar editors and wait months for response that was as often negative as positive.