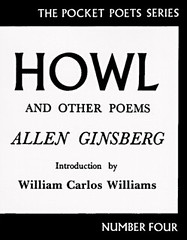

A device that is often associated with language poetry – and with surrealism – the conjoining of words from dissonant discursive schema is something that shows up as well in the work of Allen Ginsberg, right from the beginning. The phrase “hydrogen jukebox,” from the 15th line of the first section of Howl is a case in point. The line itself reads:

who sank all night in submarine light of Bickford's floated out and sat through the stale beer after

The phrase has been used for everything from Peter Schjeldahl’s selected art writings to an opera by Philip Glass that incorporates many of Ginsberg’s writings as its libretto. The phrase has its own page on Wikipedia. It’s the name of a rock band in Philly, a poetry series in the

In his Paris Review interview – conducted by Tom Clark fresh out of the

What actually triggers the discussion is a question –

The last part of “Howl” was really an homage to … Cézanne’s method, in a sense I adapted what I could to writing…. [J]ust as Cézanne doesn’t use perspective lines to create space, but it’s a juxtaposition of one color against another color (that’s one element of his space), so, I had the idea, perhaps overrefined, that by the … juxtaposition of one word against another, a gap between the two words – like the space gap in the canvas – there’d be a gap between the two words that the mind would fill in with the sensation of existence….

I was trying to do similar things with juxtapositions like “hydrogen jukebox.”

This makes great sense, at least from a certain angle, and should serve as a reminder of just how much someone like Clark Coolidge actually was able to get from Ginsberg, that the origin of Coolidge’s practice – which Robert Sward once infamously characterized as “psychedelic word salad” – was not derived entirely from Dada or surrealism. This question of a gap, of course, takes on new dimensions with language poetry – primarily through the extension of this use of disparate juxtapositions & between statements in the “new sentence.” It is precisely the cognitive dissonance between the schema hydrogen (science, bomb, technology, etc.) and jukebox (style, youth culture, music, sexuality) that Ginsberg is ultimately writing. Underneath is the implication – I’m not even sure that Ginsberg himself sees this – that these two phenomena are expressions not of two realms that have nothing to do with one another, but of a third common schema of which each is but an part, that the youth culture of the jukebox is predicated upon the power of the hydrogen atom. Ginsberg is writing in 1956 what will become explicit in the work of social theorists like Herbert Marcuse & others a decade later.

¹ Still going at that point, 1966, by his