I’m intrigued by the fact that Allen Ginsberg’s interest in what he identifies rightly as the gap of meaning that can open up between words occurs, at least partly, as a result of his interest in Cézanne, a fascination Ginsberg dates to 1949 & which certainly lasted with him through the composition of Howl in 1955. At the very same time – and in the very same town – as college student Allen Ginsberg was looking to impressionism for a means of breaking through in his writing, painters were instead discarding the referential folderol of depiction in favor of a more direct looking at the world, one in which what one sees on a canvas is paint. The disjunct between the two practices reminds me very much of a response that Ginsberg once gave to an interviewer who was trying to provoke him into saying something dismissive about language poetry. “One generation points at the moon,” Ginsberg replied, or words approximately to that effect, “The next generation notices that they’re pointing.” In fact, Ginsberg’s comments quoted here yesterday, and the gist of that long reply to Tom Clark in the Paris Review interview back in 1966 shows Ginsberg himself very much noticing that he’s pointing, very consciously tearing that process apart & “reconstituting” it, as Ginsberg quotes Cézanne saying, in Howl.

Today, we understand a phrase such as “hydrogen jukebox” very much in the light of Mark Turner’s theory of cognitive blending, a standard process of conceptual integration. In the diagram below,

hydrogen represents the first input, jukebox the second. The process is no different whether the phrase is hydrogen jukebox or green tree or, for that matter, green furiously. What Ginsberg is interested in here – and associates with Cézanne, Shakespeare & Blake (all of whom he mentions in this regard in the Paris Review interview) – is the point at which the domains of the two inputs are sufficiently dissimilar as to set up what he calls a “gap between the two words that the mind would fill in with the sensation of existence.”

That “sensation of existence” sounds to my ear one hell of a lot like what you hear when you listen to John Cage’s notorious 4’33” – whether it’s literally the sounds of the local environment plus the constant two rhythms of one’s own body (the low pulse of the blood, the high whine of synapses firing in the brain), or whatever. What Ginsberg is trying to do is to get through whatever blocks this perception, so that one sees completely the world as it really is, without entanglements, without even history or knowledge. Ditto Cage.

To get you to see this, Ginsberg attempts to get you not only to see with language, but understand where it ends & the referential world beyond begins. Thus Howl is filled with such phrases as negro streets, angry fix or starry dynamo in the machinery of night. But this widening of the gaps – and understanding, at least intuitively, the right

cognitive schema to juxtapose against one another – isn’t the only mechanism Ginsberg uses to make this palpable to the reader. Take for example the larger segment of

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night,

who poverty and tatters and hollow-eyed and high sat up smoking in the supernatural darkness of cold-water flats floating across the tops of cities contemplating jazz

the use of the word poverty at the start of the second line deliberately tilts the syntax away from grammaticality – impoverished and in tatters – showing us the schema, rather than the normative application of it. It’s an instance where the pointing at the moon & the process of pointing are allowed each to become visible. And it’s infinitely more powerful, more real even, than the same phrase would be in standardized grammar. Indeed, a secondary effect is to mimic a speaker so excited as to be stumbling over words as he tries to convey his message – a definite feature of Howl & something that differentiates it from almost all prior American poetry.

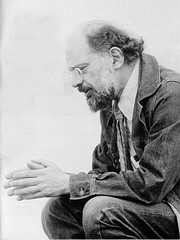

Ginsberg is so often treated as the hippy guru, part wise man, part clown, that we tend to forget just what a meticulous craftsman he was, how deeply schooled in classic verse – I once saw him teach a class on Herrick at Naropa – and how conscious he was of everything he was doing. It’s no accident that on the 50th anniversary of the publication of Howl, newspapers across the nation have taken notice of the impact of this simple little book. For many Americans, unaware of how deeply poetry had changed over the previous century, Howl was a wake up call, showing them what a contemporary verse might be.