The

world of poetry is changing. This has consequences.

Overwhelmed

by the absolute number of poets, the omnibus poetry anthology has become

impossible in book form – examples can

be judged only by the degree to which they fail. It’s a form in which the best

intentions of editors simply prove embarrassing, a circumstance that is never

aided by the fact that the motives of publishers are far more venal than those

of hapless compilers. More sharply defined collections – Poems for the Millennium,

Vol. 4: The University of California Book of North African Poetry, Beauty is a Verb, The Reality Street Book of Sonnets – succeed to the degree that the best editors are rigorous in

their containment of a given territory and honest with their readers as to what

they do (and, more importantly, do not) address.

Like

the omnibus anthology, such collections are inherently depictive: they

represent the poetry of a terrain, a social category, or a literary form. Their

virtue is to be found in their modesty of scope, their sharpness of focus and thus

the diligence of their editors. If they attempt any intervention into the

social fabric of poetry, it is primarily to indicate that X also is a part of

the landscape.

Another

type of anthology raises the stakes by adding a second, argumentative

dimension, using the anthology form to make the

case for some new understanding of the poetic whole. The classic example

– for good reason – is Donald M Allen’s The New American Poetry:

1945 – 1960 (NAP) which sold over 100,000

copies and is credited with either opening mid-century poetry up to a wealth of

new possibilities, or, alternately, triggering the irremediable decline of

civilization. Allen’s anthology was not the first such venture in English – that

would have been Pound’s Des Imagistes, which

appeared as the February 1914 issue of The

Glebe, published by Alfred Kreymborg & Man Ray. But, while both Des Imagistes & Louis Zukofsky’s

1932 An ‘Objectivists’ Anthology would

have significant long-term implications for poetry¹, neither remotely

approached the impact of the Allen.

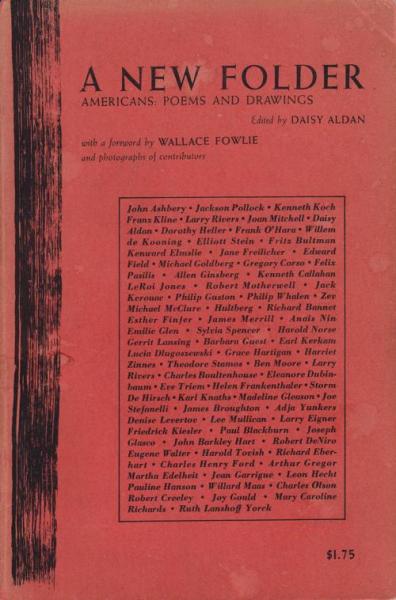

Neither did Daisy Aldan’s excellent A New Folder:

Americans: Poems and Drawings, which

appeared one year before the Allen anthology, covering much of the same

aesthetic terrain, but with some notable differences. I’m interested in why one

anthology becomes a transformative event for a generation of writers and

readers, while another, similar in scope, arguably comparable in quality and first

to market, essentially sinks out of sight. Less than a dozen copies remain

available in used book stores.

The differences are telling. As Michael Hennessey notes in his Jacket2 essay on the Aldan anthology,

the collection included over 30 visual artists. The Allen, by not including the

likes of Pollock, de Kooning, Mitchell, Kline, Rivers, Motherwell et al, presents

instead an unwavering target.

Second, Aldan’s focus was Eastern, a pre-WW2 commonplace that the Allen anthology would shatter. Of the more-than-two-dozen poets who appeared in the Allen but not the Aldan, just six – Ray Bremser, Edward Marshall, Joel Oppenheimer, Jimmy Schuyler, Gilbert Sorrentino, and Jonathan Williams – were not then significantly associated with the West Coast. Bay Area poets Aldan omitted included Robin Blaser, Robert Duncan, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Gary Snyder, Jack Spicer & Phil Whalen. Aldan also published poets that the Allen anthology not only omitted, but pretty explicitly opposed as well, such as Richard Eberhart, James Merrill, Arthur Gregor and Jean Garrigue. Yet she also included poets such as Gerrit Lansing, Eve Triem and MC Richards who could easily have appeared in the Allen.

Aldan’s

failure (or refusal) to position her book in opposition to an existing Official

Verse Culture, whether we think of it as mainstream (tho it was anything but), academic,

formalist, “cooked” or quietist, along with Allen’s brilliant notion of

organizing The New American Poetry into

five ostensible groups or movements (committing some significant acts of

fiction in his typology) has much to do with why Aldan’s collection has been

relegated to the less expensive reaches of rare book dealerships while the

Allen remains in print half a century later. Three of Allen’s five sections

have heavy West Coast associations (and Robert Duncan is a key figure in a

fourth), which made enormous sense given the degree to which the Howl prosecution and attendant media

hoopla had characterized the Beats as a San Francisco treat. In envisioning a

literary landscape where the West Coast was at least as important as the East,

Allen quite literally proposed a New America, the one that had emerged from the

Second Word War, the west having grown up almost overnight in order to support

the war effort against Japan. In many ways, The

New American Poetry was the first book to fully recognize – and make

recognizable to readers – that new United Sates.

It

didn’t help that, like both the Imagists and Objectivists before her, Aldan to

some degree stepped on her own marketing in giving her collection the same

general title – A New Folder – that

she had used for a little magazine she’d edited earlier in the 1950s. And

somebody – maybe Gerard Malanga, then her high school student – should have

asked Aldan what was so special about a folder that it should be the primary

noun in her title.

But, if Aldan’s New Folder may seem fuzzy & blurred in all the places where Allen’s New American Poetry offers the razor sharp New American Poetry, the most likely reason her volume didn’t have the impact of Allen’s tome was because she didn’t intend it to have that effect. After all, before NAP, no anthology in the United States had ever anything like the reception of the Allen. The closest prior examples of a wide-scale impact for a single collection of verse would have been the 1956 prosecution of Howl, a PR campaign concocted by the San Francisco Police Department, and the 1922 publication of TS Eliot’s The Waste Land, perhaps the most carefully calculated marketing effort ever accorded a volume of verse. Neither of those were anthologies.

But The New American Poetry, alongside Howl, Jack Kerouac’s best-selling novel On the Road, plus some other volumes

that were likewise having considerable sales – by the likes of Lawrence

Ferlinghetti, Gregory Corso, Robert Creeley & John Ashbery – very quickly

reconfigured US poetry’s relationship to an audience, to the academy (finally

unmasked for the reactionary institution it had been since the days of Walt

Whitman), and to the Manhattan-focused trade publishing industry.

The

Allen was not the first anthology that sought to change American poetry and it

wasn’t even the first to segment its content for anything other than chronology

internally – some of Kreymborg’s anthologies 40 years before divided American

poetry into three traditions that we would recognize today as modernist,

anti-modernist and hybrid (with Hart Crane heading up that division). But it

was the first to use these two aggressive editorial thrusts to align poetry

with a sense of the nation that had not previously existed. In this way, The New American Poetry 1945 – 1960 changed

the stakes for poetry, and for anthologies, from that day forward.

¹ There are multiple reasons for this in each instance. Des Imagistes appeared first in a

journal with minimal circulation and soon found itself in a crowded market

alongside three subsequent anthologies on the topic by Amy Lowell. Zukofsky’s

anthology was itself a follow-on to the much more well-distributed special

issue of Poetry that had appeared a

year earlier. The Objectivists, as it happened, didn’t have much impact on

poetry for another 30 years.